The pullup is considered by many as the ultimate test of upper body strength. As “Broscience” states, you are proving that you are literally too strong for your own body. So why is it that so many people are unable to perform them? It’s not rare to see the biggest guy in the gym, suck at being able to perform strict pullups, let alone for repetitions with perfect technique.

WHY?

As with most movements within the gym, people physically make an exercise harder than it needs to be for themselves without even realising it.

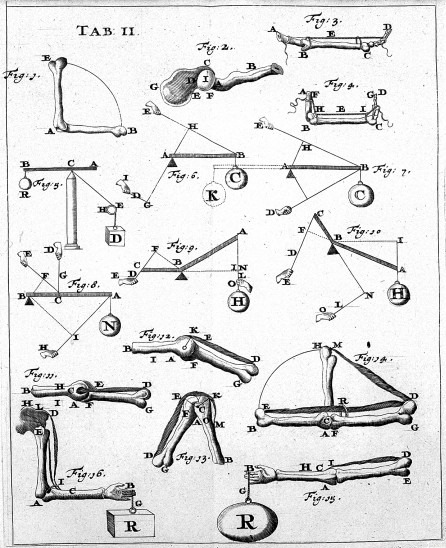

Technique and positioning doesn’t just refer to injury risk, but also the ability to maximise your performance. And this isn’t just for pullups, but in every other exercise. And the simple reason is, biomechanics.

Biomechanics in this instance refers to your joint positions, movement mechanics and your ability to manipulate the amount of force you can produce.

The pullup itself is a demanding task, requiring a fair amount of force. From an external standpoint, amount of force that must act upon your body is constant and objectively mathematical.

Don’t panic, I’m not going to break down a full calculation, but in an overly simplistic way:

If you weigh 100kg multiplied by gravitational force (9.81x 100 = 981N), you simply have produce more than this to move your body in the opposite direction. That remains unchanged for as long as gravity is constant.

HOWEVER, how much force YOU can generate on a joint level is where biomechanics and muscle activation comes into it.

WHERE SHOULD WE FOCUS?

Ask yourself, whenever you have tried to perform a pullup, where do you feel the movement? Where do you feel weakest? 9/10 most people will say their arms. Everyone always thinks their arms are the key driver within the pullup, however whilst they are involved, early research found that the shoulder girdle produces most of the force, with the muscles attached to the wrist/elbow being “minimal” in contribution (1).

The shoulder joint is where many of the answers lie. Once you understand where to position it, every aspect of the movement becomes easier.

WHICH MUSCLE FOR WHICH PHASE?

Early Phase

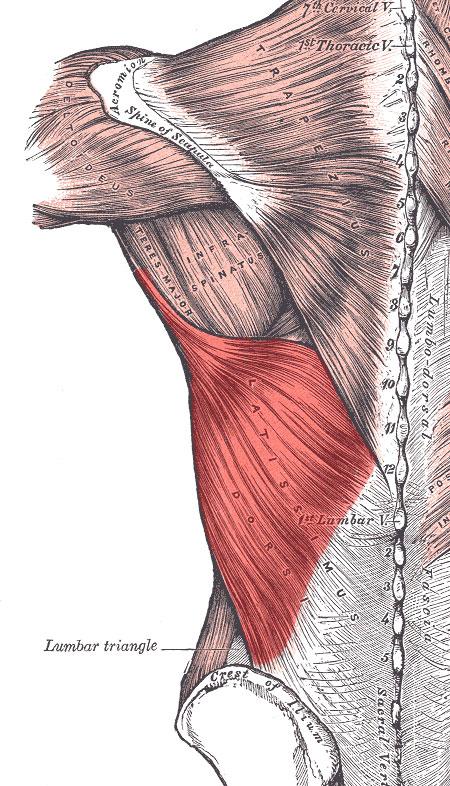

Think about it logically and refer to your own experiences. The hardest part of the pullup is getting out of the bottom and getting to about 90 degrees of elbow flexion. Research has shown that the “early phase” is largely governed by the latissimus dorsi and rotator cuff musculature (10).

Mid Phase

Within the middle phase, activation of certain muscle groups reduces slightly (e.g. biceps). However, the two major muscles that remain elevated, and in fact become even more involved, are the latissimus dorsi and teres major (10). Wait, we’ve seen one of those muscles already in this movement, right?

Final Phase

I bet you can’t guess which muscle remains high in activation? That’s right, the latissimus dorsi yet again, was found to be the highest activated muscle within this phase (10).

Although there are several other muscles acting upon the shoulder during the pullup, in the interest of getting the most out of your training, lat strength is going to have a huge impact on your ability to perform a pullup effectively and if I were you, I would start there.

EXERCISE EXECUTION

This is where a lot of the disparity comes from within the research. Some of the literature will state that peak activation occurs within the brachio-radialis and middle trapezius (3), whilst others state the latissimus dorsi is the most prevalent (10).

However, this is where most the problems lie and reasons why most people are unable to crack this exercise. As mentioned earlier, the WAY in which you perform the exercise will have a huge impact on the resultant difficulty.

Within the studies mentioned above, the specific instructions given to the participants were not provided, meaning we have no idea HOW they were executing the movement. In addition, research has shown that verbal coaching cues given from coaching can significant impact the activation of the muscles involved (8). Just because it’s called a “chest press” doesn’t mean your “chest” is always involved!

WHICH GRIP POSITION DO YOU USE?

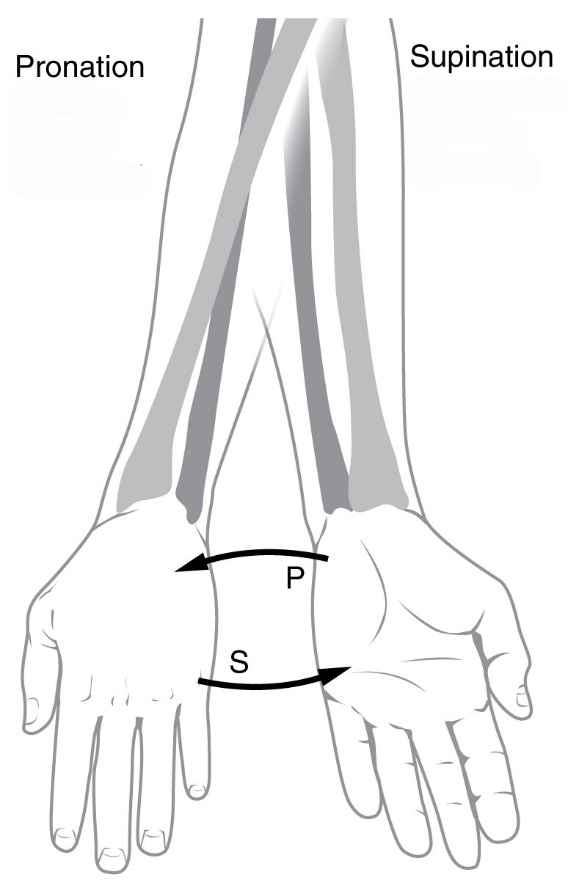

This is largely open to opinion and I will be drawing a few conclusions from my own 121 work however, I always recommend starting with a neutral grip position before moving onto a pronated/supinate grip.

There has been a couple of studies investigating the effect of different grip positions on muscle activation often finding the latissimus dorsi to be more active during a pronated (palms facing forward) pullup than when compared to a supinated alternative (6).

HOWEVER, the degree of rotation at the shoulder in ever day life also plays a huge role in determining how easily an exercise can be performed and it’s resultant injury risk.

A recent epidemiology study found a large percentage of the general population displaying some degree of internal rotation (palms turning inwards) at the shoulder (9), due to societal issues and wrongly perceived ideas of what constitutes “good posture”. But I won’t discuss good posture today, that’s for another time!

Therefore, to go into an overhead position with this inwardly rotated position, is more likely to result in shoulder impingement (3) unless you are mobile and have relatively good dynamic stability of your shoulder.

However, to begin with you can go too far the other way. Although an externally rotated shoulder (crook of the elbow facing forward) is more optimal for preventing shoulder injuries, in a supinated position, there is a greater stretch on the latissimus dorsi muscle, altering its “starting strength” and sometimes making it even harder.

COMMON ERRORS

Most people mess up right from the offset by again thinking that this exercise only involves your upper body. However below are a couple of common errors you may have made:

-

GLUTE AND CORE STABILITY

Your glutes and core – squeezing your glutes as hard as possible prevents your lower body from ‘sagging’ and essentially become dead weight during the exercise. Furthermore, recent research has found force transmission through connective tissue to occur between the glutes and latissimus dorsi (4). However, if you focus on generating as much tension and stability as possible, it helps eradicate the problem.

Although this article isn’t about what we determine “the core” to be, this region of the body does in fact include the erector spinae and the rest of the muscles within the “mid-riff”. I cannot stress the importance of your core when performing all manner of exercises, but within the pullup it is even more crucial for effective execution. Research has shown that the erector spinae assists with pelvic stability throughout the movement, giving the latissimus dorsi a stable fixation site to pull against, particularly towards the end of the movement (10).

-

YOUR SHOULDERS LIFT

One of the key drivers for strength within the pullup is your lats (largely dependent upon the grip that you choose). However, a large quantity of the movement comes from shoulder extension. If you elevate your scapula, you place the lat in a stretched position, this alters the length-tension relationship and therefore means that the muscle is much weaker right from the offset. Pull your shoulders down and keep your head tall.

Furthermore, a new research has found that a high arm elevation (i.e. your shoulder lifting), creates greater stress on the sub-acromial space of the shoulder joint and therefore increases the risk of shoulder impingement injuries (7). The researchers within this study also stressed the importance of focusing on the starting scapula position during the start of the movement (7).

-

DID THAT PULLUP COUNT?

Let’s face it, due to the difficulty of the exercise, it’s far too common to see people performing “half reps” in which they don’t go through a full range of motion. However, when only performing partial range of motion, research has shown that whilst you can get stronger, you may not develop at other joint angles (5). You essentially get better at what you do and only that. Sounds obvious, right?

SUMMARY

– Start with a neutral grip.

– Develop overall latissimus dorsi strength through alternative exercises such as pulldowns.

– Learn how to brace your core and your glutes whilst your shoulders are moving under load.

– Pull your shoulders down away from your ears.

REFERENCES

- Antinori, F., Felici, F., Figura, F., Marchetti, M., & Ricci, B. (1988). Joint moments and work in pull-ups.J Sports Med Phys Fitness, 28(2), 132-7

- Boccia, G., Pizzigalli, L., Formicola, D., Ivaldi, M., & Rainoldi, A. (2015). Higher Neuromuscular Manifestations of Fatigue in Dynamic than Isometric Pull-Up Tasks in Rock Climbers.Journal of human kinetics, 47(1), 31-39

- Dickie, J. A., Faulkner, J. A., Barnes, M. J., & Lark, S. D. (2017). Electromyographic analysis of muscle activation during pull-up variations.Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 32, 30-36

- do Carmo Carvalhais, V. O., de Melo Ocarino, J., Araújo, V. L., Souza, T. R., Silva, P. L. P., & Fonseca, S. T. (2013). Myofascial force transmission between the latissimus dorsi and gluteus maximus muscles: an in vivo experiment.Journal of biomechanics, 46(5), 1003-1007

- Graves, J. E., Pollock, M. L., Jones, A. E., Colvin, A. B., & Leggett, S. H. (1989). Specificity of limited range of motion variable resistance training.Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 21(1), 84-89

- Leslie, K. L., & Comfort, P. (2013). The effect of grip width and hand orientation on muscle activity during pull-ups and the lat pull-down.Strength & Conditioning Journal, 35(1), 75-78

- Prinold, J. A., & Bull, A. M. (2016). Scapula kinematics of pull-up techniques: Avoiding impingement risk with training changes.Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 19(8), 629-635

- Snyder, B. J., & Fry, W. R. (2012). Effect of verbal instruction on muscle activity during the bench press exercise.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(9), 2394-2400

- Walker‐Bone, K., Palmer, K. T., Reading, I., Coggon, D., & Cooper, C. (2004). Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb in the general population.Arthritis Care & Research, 51(4), 642-651

- Youdas, J. W., Amundson, C. L., Cicero, K. S., Hahn, J. J., Harezlak, D. T., & Hollman, J. H. (2010). Surface electromyographic activation patterns and elbow joint motion during a pull-up, chin-up, or perfect-pullup™ rotational exercise.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3404-3414