Time under tension is arguably the most important variable when it comes to building muscle and strength, but how do we take hold and use it, to give us the best results?

Adjusting the tempo of an exercise is one of the most undervalued and yet remarkably effective methods of maximising your strength.

Set the Scene

No matter how hard you try, you just can’t seem to get your chest to grow. You have rotated every exercise known to man, used heavy loads vs. lighter weights, supersets…every trick you can think of…and yet no success.

Or perhaps you find yourself loving every aspect of strength training – except for one exercise. It may be the squat, it may be the bench press (let’s face it – it’s probably not going to be the deadlift) – but when it comes down to it, you and that exercise just don’t agree with one another.

Now although there are hundreds of variations that can work you towards a common goal – at some point you’re going to have give in and work on it. We know that a weakness in your arsenal is the first place to start on the Journey to Strong…but how do we overcome the awkwardness and maximise our results?

Chapter One – What Is Tension?

WHAT?

Learn the topic.

In the world of strength training, we often focus on the numbers. The variables that we can tweak to bring about the adaptation we ultimately want, the main 3 being:

- Sets

- Reps

- Load

However, when we boil it down to the main thing we’re aiming to achieve, they all work together to maximise the amount of tension placed through the body.

What is Tension?

Sounds like an incredibly simple question, but when prompted, most people don’t understand what it actually is.

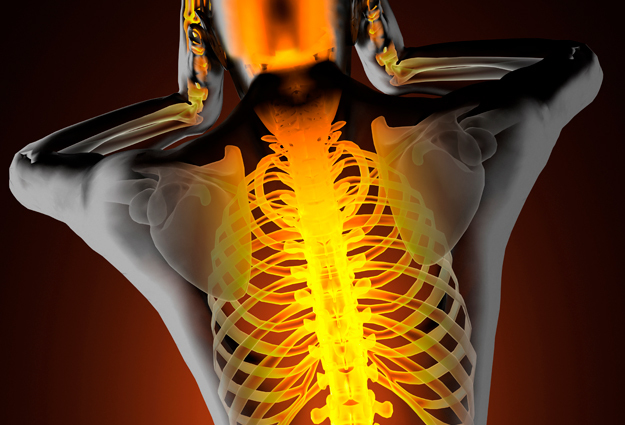

Being “tense” is often deemed a bad thing, being the key characteristic of people’s neck pain or lower back “tightness”.

However, tension isn’t all bad.

In fact, in the world of strength, tension is king.

Biology, Neurochemistry and Other Bits of Science

If you look dig into the biology behind tension, it becomes relatively clear what it is –

Electrical activity within muscle tissue either at rest or during contraction.

Now, for our purposes, we’re going to focus on two main forms of tension – resting/passive and active tension.

Resting/Passive

When “resting” you think your body is…well…resting. You’re not really moving, so the muscles aren’t working, right?

Not exactly. In fact, the only time in which the skeletal muscles of the body truly relax is during REM sleep, in which the brain shuts off all forms of activation to muscle to prevent extraneous movement (this is one of the reasons REM sleep is so essential for recovery).

Just a Quick One...

In the case of the article, “rest” will be defined as anything that isn’t an athletic, metabolically demanding movement (i.e. walking about day to day, standing talking to your mates or sitting reading right now).

During rest the body is constantly fighting two primary forces:

- Gravity. That sucker doesn’t ever want to let up and wants to drag you down to the floor every second of every day.

- Tensile Forces from other muscles. Muscles don’t just pull on bones. They pull on other muscles. Meaning if you have an area surrounding a joint that it is particularly weak, the other muscles will take up the slack, tugging on the joint harder than it should, therefore limiting it’s range of motion (or “flexibility”) to try and stabilise it.

The 2nd scenario is what most people experience day to day, that causes the blinding headaches and the uncomfortable sensation when leaning over etc.

The electrical activity is relatively low, but it’s there, constantly switched on (think of a dimmer light switch on it’s lowest setting).

Active Tension

Muscular contraction is a pretty clever feat of biological engineering that produces tension, creating movement. A pulling force that moves one point to another.

Now the amazing thing with the human body is that there are two “governors” that determine how much tension you can produce –

- Voluntary Contraction – this is basically what you can “choose” to produce, when performing a movement or when being told to “tense” a muscle.

- Neurological Inhibition – This is the involuntary side.It doesn’t matter what you want or how hard you try, your body will down regulate what you’re truly capable of, if it thinks there is a potential for damage or injury. And this is why technique (at least for 99% of the population) is so incredibly important. It’s not just to stay safe and hope you don’t get injured, it’s to optimise your performance and allow your body to become the strongest body it can be. It’s arguably the number one most forgotten truth of training – strength is a skill.

Let’s use the example of “shoulder stability”.

Most people lie down on the bench, unrack the bar and completely disregard the notion of creating tension.

As a result, they end up with two scenarios:

- Shoulder or elbow pain that just won’t f*ck off and leave them alone.

- Hitting a plateau and never breaking past it.

In either situation, the body is sensing that something “isn’t quite right” and therefore won’t risk the potential damage if the weight was to increase.

Generating active tension in the upper back, creating a stable arch and building tension in the legs however, will help solve either of those problems.

Tempo – Build Time Under Tension

Repetition Tempo refers to the time in which it takes you to complete each phase of a movement.

Almost every isotonic exercise you perform is characterised by the following:

- Eccentric phase – lowering the weight.

- Isometric phase – the pause/transition from the lowering to the lifting.

- Concentric phase – the lifting of the weight

Depending upon the exercise, the eccentric phase might be first, or last, starting with the concentric phase first (e.g. deadlift vs the bench press).

In a training plan, the training tempo would be referred to as something like the following:

- 1,1,1,1 = 1 second lower, 1 second pause, 1 second lift, 1 second pause.

- 3,3,3,3 = 3 second lower, 3 second pause, 3 second lift, 3 second pause.

And so on…

What’s More Important?

So you may be wondering…what’s the point in tension? Surely, more reps = more time under tension, right?

Not necessarily.

A recent study by Wilk et al. (12) found that a slower tempo of movement resulted in a greater amount of time under tension, despite the number of reps per set dropping significantly when compared to the faster tempo group.

The authors summarised…

“If time under tension increases, the volume of the work also increases, regardless of the number of repetitions performed (Wilk et al., 2018).”

However, there’s a bit of a problem.

What Classes as ‘Slow’?

The paper above by Wilk et al. (12), found that a tempo of 5,0,3,0 was superior to 2,0,2,0 for eliciting extra training volume.

And yet, Hatfield (6) & Kim et al. (7), found that training volume and strength may be negatively affected by slow duration contractions, despite increasing the time under tension.

The difference?

In the case of the Hatfield and Kim studies, the tests involved 10 second tempos for both the eccentric and concentric phases.

The Real World

To put it bluntly, you’d be very hard pressed to find someone willing to do a 10 second duration when lifting (in either the eccentric or concentric portion).

And, it simply doesn’t make sense to do so.

When we’re interested in developing muscle strength (and/or size), time under tension is essential. However, so is the magnitude of tension, as shown with using mechanical tension to maximise muscle growth.

Using a duration that extends beyond 5 seconds will result in such a drastic decrease in the weight lifted, meaning the tradeoff (of having more time under tension in each rep), simply isn’t worth it.

And this is one of the limitations of the research vs. application. What is defined as “slow” and more “time under tension” in the lab, is pretty much completely inpractical in the real world.

So, it’s important to make the following distinction:

Movement Tempo | Duration in Research | Duration in Real World Lifting |

|---|---|---|

Slow | Up to 10 seconds | 5 seconds+ |

Moderate | 3 to 5 seconds | 2 to 4 seconds |

Fast | 3 seconds or less | Less than 2 seconds |

Chapter Two – Science of Time Under Tension

Why Change the Tempo?

Greater Muscular Involvement

When you lift a weight, there is something known as passive tissue contribution.

This refers to the elastic energy stored during the lowering phase of an exercise, that is then released during the concentric phase (8).

Think of an elastic band…or drawing tension into a bow and arrow.

However, when we remove this element by controlling/slowing the tempo down as we lower the weight, we actually increase the muscular tension generated when lifting it (5).

So not only do we get greater muscle involvement, but we also get…

…Greater Muscle Growth

Research has shown that slowing down the eccentric phase (and the whole tempo of the movement) can have a favourable affect on muscle growth (2, 3, 4).

A study by Martineau (9), also found that mechanotransduction (a process through which muscle growth occurs), is sensitive to time under tension, and peak tension, but less sensitive to the rate at which it is applied. In other words a muscle that is rapidly stretched doesn’t necessarily experience a greater mechanical response than a muscle that is stretched at a slower rate, with the same weight being lifted.

The speed at which you move has a greater bearing on the nervous system and the connective tissue, as oppose to the actual muscle.

Now as we mentioned earlier…we don’t want to slow the movement down to the point where the weight you’re lifting significantly drops, but controlling the weight is far more important than people often realise.

Greater Biofeedback

You can notice things wrong with your own technique and correct them as you’re performing the exercise.

Think about the squat movement.

If you simply drop down and bounce back up again for 10 reps, you might not notice that during the 4th and 8th rep, you drifted onto your toes a little more than usual, or that your knees caved in.

Slowing the tempo down is a great way of eliminating the likelihood of those faults occuring.

Reduced Injury Risk

As we’ve discussed before:

The faster you move through a movement, the greater the risk of creating damage to the muscular system (11).

Greater Perceived Effort

Take a weight that feels difficult and slow it right down – it’ll make it feel like it weighs a tonne heavier. Trust me.

More Volume = Less Recovery

The final point to make, is how adjusting tempo can help you to get more work done, without taxing your recovery.

It’s easier to get caught up in the notion that the only way to progress an exercise is to add more weight.

However, remember that more weight = more mechanical demand.

More mechanical demand = harder to recover from.

In other words, keeping the weight lighter and adjusting the tempo, allows you to generate more tension in the muscle without taxing your body as much as you would lifting heavy.

So, be savvy with the way you progress each exercise. Don’t always just slap on more weight and hope for the best.

Chapter Three – The “How To” of Tempo

Slowing down the tempo is a great tool for improving technique during a movement.

So what determines whether or not we should slow the tempo down?

New = Slow, Advanced = Fast

This is where the individuality element comes into play.

The tempo you should use depends primarily on three factors.

1. Your Training Status

If you’re new to the world of lifting, a slower tempo is recommended in order to help improve your technique and decrease risk of injury (1).

Typically, the more advanced/experienced you are – the more control you tend to have over the exercise, without even realising it. As a result you can move faster, whilst keeping the muscle tense throughout the movement.

Are You Injured?

Yeah, I get it. Being injured sucks. And annoyingly, it usually happens when you least expect it…and when everything seems to be going well.

Suffering from an injury has several downsides…one of which is the lack of hard training.

Most of the time, we actually enjoy working hard – and the injury stops that from happening.

However, implementing purposefully slow training is a great way to continue the feeling of exertion without the need of exacerbating the injury you’re currently suffering from…just whilst you give time for your body to recover.

2. Skill in the Exercise and the Exercise Itself

You may be advanced, but that doesn’t mean you’re great at everything. You may find that in one area you’re doing great, yet in another you’re struggling to grasp the movement. In this case a slower tempo may also be appropriate.

It also depends on the exercise you’re performing. For example, olympic lifting (such as the snatch or clean and jerk) and anything requiring power are pretty much exempt from adjusting the tempo.

Go ahead and try jumping as slowly as possible. Doesn’t really work too well.

3. The Goal of the Exercise

The FINAL thing to ask yourself is: What is the goal of the exercise?

If the goal is to build maximal strength in that specific movement, then you probably want to focus on maximal strength. This typically involves being as stable as possible during the lowering phase of and being as explosive as you can during the lift.

Taking this scenario, it wouldn’t make sense to perform a rapid lowering phase and then a really slow lifting phase, would it?

Research has shown the speed of the movement (as well as the load) to directly influence how the nervous system responds. Keeping the lowering phase the same, one group was told to lift as fast as possible, whilst the other aimed to lift with 1/2 of their maximum speed.

Unsurprisingly, the group that performed the concentric/lifting phase as fast as possible – got stronger and faster over the course of the program (10).

On the other hand, if you are utilising an exercise to build muscle in a lagging area (that ultimately affects your strength in the movement you’re after) and you struggle to activate it during an exercise, then slowing the tempo down throughout the whole movement is a great way of bringing awareness to the muscles involved and a way of increasing the intensity of the exercise without needing to use as much weight.

Summary

- Tension is strength. The tighter you are, the stronger you are.

- There are two types of tension – Passive Tension = usually caused by weakness or poor mobility. Active Tension = how hard you can contract a muscle.

- Slowing the tempo down during an exercise, is a great way to: 1. Increase time under tension, 2. Improve biofeedback, 3. Train around an injury and 4. Increase your perceived effort, 5. Increase training volume without taxing your recovery as much.

- Deciding which tempo you should use is based off: 1. Training Status, 2. Skill during the exercise and the exercise itself, 3. The Goal during the exercise.

References

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2009). American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 41(3), 687

- Bird SP, Tarpenning KM, Marino FE. Designing resistance training programmes to enhance muscular fitness:

A review of the acute programme variables. Sports Medicine, 2005; 35: 841-851 - Burd NA, Holwerda AM, Selby KC, West DW, Staples AW, Cain NE, Cashaback JG, Potvin JR, Baker SK, Phillips SM. Resistance exercise volume affects myofibrillar protein synthesis and anabolic signalling molecule phosphorylation in young men. J of physiol, 2010; 588: 3119-3130

- Gehlert S, Suhr F, Gutsche K, Willkomm L, Kern J, Jacko D, Knicker A, Schiffer T, Wackerhage H, Bloch W.

High force development augments skeletal muscle signalling in resistance exercise modes equalized

for time under tension. Pflugers Arch, 2015; 467: 1343-1356 - Golas A, Maszczyk A, Stastny P, Wilk M, Ficek K, Lockie RG, Zajac A. A New Approach to EMG Analysis of

Closed-Circuit Movements Such as the Flat Bench Press. Sports, 2018; 6(2): 27 - Hatfield, D. L., Kraemer, W. J., Spiering, B. A., & Häkkinen, K. (2006). The impact of velocity of movement on performance factors in resistance exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(4), 760

- Kim, E., Dear, A., Ferguson, S. L., Seo, D., & Bemben, M. G. (2011). Effects of 4 weeks of traditional resistance training vs. superslow strength training on early phase adaptations in strength, flexibility, and aerobic capacity in college-aged women. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(11), 3006-3013

- Lindstedt SL, Reich TE, Keim P, LaStayo PC. Do muscles function as adaptable locomotor springs? J Exp Biol,2002; 205: 2211-2216

- Martineau, L. C., & Gardiner, P. F. (2002). Skeletal muscle is sensitive to the tension–time integral but not to the rate of change of tension, as assessed by mechanically induced signaling. Journal of biomechanics, 35(5), 657-663

- Pareja-Blanco, F., Rodríguez-Rosell, D., Sánchez-Medina, L., Gorostiaga, E. M., & González-Badillo, J. J. (2014). Effect of movement velocity during resistance training on neuromuscular performance. International journal of sports medicine, 35(11), 916-924

- Westcott, W. L., Winett, R. A., Anderson, E. S., & Wojcik, J. R. (2001). Effects of regular and slow speed resistance training on muscle strength. Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 41(2), 154

- Wilk, M., Golas, A., Stastny, P., Nawrocka, M., Krzysztofik, M., & Zajac, A. (2018). Does tempo of resistance exercise impact training volume?. Journal of human kinetics, 62(1), 241-250