Where the hell do I start? You may have asked yourself this when you either first walk into the gym, or when you’ve decided to finally branch out on your own and try training for yourself and choosing strength exercises for yourself. First thing that comes to most minds when they look at a dumbbell/barbell is Arnold Schwarzenegger…cue, the bicep curl. It’s easy, simple to execute and let’s face it…everyone wants big arms, right? Whilst you may be dreaming of the day that your biceps are ripping your shirt and you can look much cooler stood by the bar holding on to your bottle and head bopping to the club music…you’re wasting your time.

Where the hell do I start? You may have asked yourself this when you either first walk into the gym, or when you’ve decided to finally branch out on your own and try training for yourself and choosing strength exercises for yourself. First thing that comes to most minds when they look at a dumbbell/barbell is Arnold Schwarzenegger…cue, the bicep curl. It’s easy, simple to execute and let’s face it…everyone wants big arms, right? Whilst you may be dreaming of the day that your biceps are ripping your shirt and you can look much cooler stood by the bar holding on to your bottle and head bopping to the club music…you’re wasting your time.

TWICE THE RESULTS + HALF THE TIME

Irrespective of the facet in life, efficiency and optimisation should be a key focus. Why spend more time on a task, when you get twice the results in half the time? Now this isn’t one of those, “Lose 40lbs of fat and gain 300lbs of muscle in 24 hours” kind of schemes; results do take time and there are certain physiological limitations regarding the rate of progress (irrespective of what some people say), however there are simple ways to optimise your time in the gym.

GET A LIFE!

I love the gym and all forms of exercise and continue to fuel my obsession every day. I spend at least 50 hours a week in a gym, whether working or training and I’m here to tell you one thing…get a life. Despite my passion, I don’t live my life purely for a gym. So why do I see other people checking into the gym and spending 5 hours a day in there? What about your friends? Family? Your own personal development? Keep in mind, unless you want to be a strength and conditioning coach or professional athlete, the gym should be a supplement to the rest of your life, it shouldn’t take over it.

From working with people that have spent over a decade in the gym and getting absolutely no-where near where they want to be, I’m here to tell you how you can optimise your time in the gym, gain more results and more free time.

SQUATS…OR LEGS?

This is the number one talking point of this article. I have consistently applied this not only to my own training, but the choice of strength exercises with my own clients, athletes and reviewed the training methodologies of athletes around the world.

Don’t suppose this sounds familiar?

Monday – Chest and Tris

Wednesday – Back and Bis

Saturday (can’t do Friday due to being ‘out’) – Legs and Shoulders

You may not structure it exactly like that, but basing your training sessions around the muscles being trained stems purely from the bodybuilding philosophy, which has tended to control most of the fitness industry (with respect to the weights). Answer this question, are you a bodybuilder? Do you have any desire to compete on stage? No? Well then, why would you structure all of your training around what muscles you’re going to “hit”?

DO YOU EVEN MOVE, BRO?

Referring to my previous point, the whole point of training is to not only look better, but feel better as well, right? If I offered you 5% body fat, but you feel like you’re immobile, can’t sit in a chair for too long and struggle to get off the floor vs. possessing 10% body fat but being able to move like an athlete, which would you choose? If it’s the former, then I strongly recommend you leave this page as this advice won’t be any use to you.

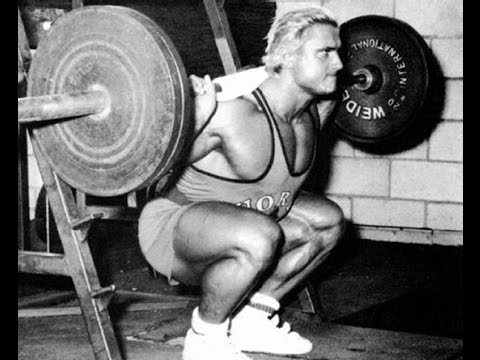

SQUATS (FULL DEPTH)

Front. Back. Goblet. Landmine. Overhead. Bodyweight.

But a squat should be a fundamental aspect of your training. Not only has there been extensive research highlighting that increasing depth of the squat is superior for activation (3, 7) but for all you “research doesn’t mean shit” people… Tom Platz, known for having perhaps the greatest set of legs in bodybuilding history, notoriously squatted full depth.

Now before you all get arsy, full depth is objective; but also, entirely individual. Depending upon your anatomical and anthropomorphic make up, certain people find it easier to squat until their glutes are touching the floor, where as others can just about break parallel. So where do you draw the line?

Until your movement pattern within the strength exercises begins to break down.

An example includes significant posterior pelvic tilt (PPT), more commonly referred to as ‘butt wink’. Keeping your spine neutral and preventing pelvic rotation is essential for preventing shear forces in the lumbar spine (6, 14).

HIP HINGE

Deadlift. Romanian Deadlift. Stiff Legged Deadlift. Kettle-bell Swing.

The number of chronic lower back problems I have encountered with my clients that is more or less exclusively caused by an inability to hip hinge. If you want, you can check out my other article on “7 Reasons why Absolutely Everyone Should Deadlift” to explain in a bit more detail, but the ability to effectively coordinate hip flexion followed by rapid extension is essential for health and performance in almost every single sport you could name.

The number of chronic lower back problems I have encountered with my clients that is more or less exclusively caused by an inability to hip hinge. If you want, you can check out my other article on “7 Reasons why Absolutely Everyone Should Deadlift” to explain in a bit more detail, but the ability to effectively coordinate hip flexion followed by rapid extension is essential for health and performance in almost every single sport you could name.

Increasing jump height? Research has shown that greater jump heights involve an increased moment at the hip (11).

Want to run faster? Research has also shown that increasing sprint velocity involves a greater moment at the hip (13).

PUSH

Bench Press. Military/Overhead Press. Press Ups. Handstand Press Ups.

The ability to effectively co-ordinate your scapula with your glenohumeral aspect of the shoulder is essential to prevent any limited movement in your thoracic spine and optimise sporting performance (10). Often, a “kyphotic posture” is caused by internal rotation of the shoulder and poor shoulder proprioception (8). In addition, head and shoulder postural position has been shown to significantly influence scapular mechanics and muscular activity during overhead tasks (15).

In other words, if you’re walking around looking like Quasimodo from Hunch Back of Notre Dame, it’s probably down to your poor shoulder function. Learn how to push things effectively and those problems are likely to disappear.

PULL

Bent Over Row. Pendlay Row. Pullups. Pulldowns.

“Pulling” strength exercises involves a significant contribution from what is commonly referred to as the “posterior chain”. The posterior chain consists of large tendons, ligaments and muscle groups including the back, legs and hip musculature that are highly active during a variety of extension based tasks (5). Research has also highlighted the importance of back strength in the prevention of lower back pain later in life (12). Combine this with an effective hip hinge and you’re good to train knowing you’re doing yourself a favour, not damage.

Due to society, nowadays, we spend a lot of our time sat down and relatively immobile, meaning this section of the body becomes significantly weaker, day by day. Neglecting your posterior chain musculature can significantly hinder your posture, mobility, flexibility and overall sporting performance (2).

Not only does the posterior chain have a significant role to play in health and the maintenance of good posture, several sporting tasks are dominated by the neuro-muscular contribution from this series of muscle groups (1, 9).

TRIPLE EXTENSION

Jumping. Olympic Lifting. Sprinting.

A missing link for most people who train in a gym. Except for athletes and strength and conditioning coaches, most people have absolutely no idea what triple extension even is.

Triple extension involves the co-ordination and rapid extension of the ankle, knee and hip joint from a flexed position. Although it might not be an absolute necessity for your average gym goer on the surface, the ability to triple extend carries with it a certain element of dynamism that carries over to a multitude of tasks in daily life and is a great way to inform the choice of strength exercises used.

Not to mention, that if you are aiming to improve sporting performance across a range of tasks, triple extension is a key action that inevitably will be performed and determine success (16).

SUMMARY

I have consistently stated that the choice of strength exercises with which athlete’s train is something to aspire to, and there you have it. Rather than thinking about the muscles you need to train, begin to base your selection of strength exercises around the movements covered, the aesthetic gains will follow later.

REFERENCES:

- Bennell, K. L., & Crossley, K. (1996). Musculoskeletal injuries in track and field: incidence, distribution and risk factors.Australian journal of science and medicine in sport, 28(3), 69-75.

- Brown, S. R., Brughelli, M., Griffiths, P. C., & Cronin, J. B. (2014). Lower-extremity isokinetic strength profiling in professional rugby league and rugby union.International journal of sports physiology and performance, 9(2), 358-361.

- Caterisano, A., Moss, R. E., Pellinger, T. K., Woodruff, K., Lewis, V. C., Booth, W., & Khadra, T. (2002). The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 16(3), 428-432.

- Comfort, P., & Kasim, P. (2007). Optimizing Squat Technique.Strength & Conditioning Journal, 29(6), 10-13.

- De Ridder, E. M., Van Oosterwijck, J. O., Vleeming, A., Vanderstraeten, G. G., & Danneels, L. A. (2013). Posterior muscle chain activity during various extension exercises: an observational study.BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 14(1), 204.

- Delitto, R. S., & Rose, S. J. (1992). An electromyographic analysis of two techniques for squat lifting and lowering.Physical therapy, 72(6), 438-448.

- Gorsuch, J., Long, J., Miller, K., Primeau, K., Rutledge, S., Sossong, A., & Durocher, J. J. (2013). The effect of squat depth on multiarticular muscle activation in collegiate cross-country runners.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 27(9), 2619-2625.

- Greenfield, B., Catlin, P. A., Coats, P. W., Green, E., McDonald, J. J., & North, C. (1995). Posture in patients with shoulder overuse injuries and healthy individuals.Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 21(5), 287-295

- Hawkins, R. D., Hulse, M. A., Wilkinson, C., Hodson, A., & Gibson, M. (2001). The association football medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football.British journal of sports medicine, 35(1), 43-47.

- Kibler, W. B. (1998). The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function.The American journal of sports medicine, 26(2), 325-337

- Lees, A., Vanrenterghem, J., & De Clercq, D. (2004). The maximal and submaximal vertical jump: implications for strength and conditioning. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 18(4), 787-791.

- Luoto, S., Heliövaara, M., Hurri, H., & Alaranta, H. (1995). Static back endurance and the risk of low-back pain.Clinical biomechanics, 10(6), 323-324.

- Schache, A. G., Blanch, P. D., Dorn, T. W., Brown, N. A., Rosemond, D., & Pandy, M. G. (2011). Effect of running speed on lower limb joint kinetics. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 43(7), pp. 1260-1271.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3497-3506.

- Thigpen, C. A., Padua, D. A., Michener, L. A., Guskiewicz, K., Giuliani, C., Keener, J. D., & Stergiou, N. (2010). Head and shoulder posture affect scapular mechanics and muscle activity in overhead tasks.Journal of Electromyography and kinesiology, 20(4), 701-709

- Timothy, J. (2013). Baseball Resistance Training: Should Power Clean Variations Be Incorporated?Journal of Athletic Enhancement.