If you haven’t already I strongly recommend you head on over to Part 1 (Women Who Lift – Why Women Should Strength Train) and give it a quick read to understand a few scientific reasons behind why females should be regularly lifting! So, now we know why, we need to understand how. Now for the feminists out there, I am sorry to announce that you should not be doing the same as men.  Or at least not everything the same. You can go ahead, but there are certain advantages that women possess over men in the realms of muscle and strength development, so why wouldn’t you train to those strengths?

Or at least not everything the same. You can go ahead, but there are certain advantages that women possess over men in the realms of muscle and strength development, so why wouldn’t you train to those strengths?

SCIENTIFIC BIAS

Unfortunately, throughout the coaching and even the scientific community, there is a strong bias towards the use of the male population in research studies (2, 3, 6, 28, 29, 42) and to therefore inform training recommendations. Now, I’m not going to go into the social-sexist-economical-philosophical reasoning behind this, but note that current recommendations (largely based from males) are sub-optimal for the female athlete. Fortunately, this article should give you an insight into the differences between training recommendations for females and allow you to reap the rewards being a female can bring! Thankfully, there is a plethora of research available investigating sex differences within resistance training that can hopefully clear some of the misconceptions.

THE RESEARCH:

FATIGUE RESISTANCE

This is arguably the biggest advantage females possess. Research has consistently shown an increased fatigue resistance during a range of contraction types and populations during single limb and respiratory muscle contractions (8, 13, 20, 21, 22, 23, 35). One study found that strength-matched women could perform an intermittent isometric (static) task to failure almost 3x longer than men! (22).

This isn’t just limited to static/isometric contractions either, with greater fatigue resistance being found during dynamic movements (32). It is important to note however, that when intensity increases, the superiority of females begins to reduce slightly, but usually still remain more resistant to fatigue than men.

With muscle fatigability being a primary vehicle for promoting overload and adaptation of the neuromuscular system (1, 5, 25, 30), women are in a pretty good situation! Thus, this means that women can perform a greater number of repetitions each set and an overall greater submaximal volume.

FASTER RECOVERY RATES BETWEEN WORKOUTS

Females have also been found to recover faster than males between highly intense strength based workouts. In one study, no significant differences in strength levels were observed during a strength test, 4 hours after a 5RM bench press workout (27). In addition, there is support within the literature that women may benefit from splitting their total training volume across two daily training sessions (increasing training frequency) (15) despite previous research finding no significant strength benefits with twice daily training in males (17).

And no. Before you say it. This is not to do with differences in strength level/muscle size. Contrary to popular belief, the fact that men possess greater muscle size and strength doesn’t always have a significant impact on their inability to fatigue when compared to women. This is supported by the research by Judge & Burke (27) finding that a control group consisting of males (who were strength-matched with female’s athletes) still experienced greater levels of muscular fatigue than females. They concluded that training background (i.e. muscle strength and size) did not influence gender differences in fatigue resistance.

Whilst it may be different up at the elite level, the current research surrounding novice to intermediates suggest that women are just more fatigue resistant than men, irrespective of the relative weight being lifted.

WHAT EXPLAINS THESE BENEFITS?

Largely, this can all be explained by two major factors: fibre type distribution and the circulatory system.

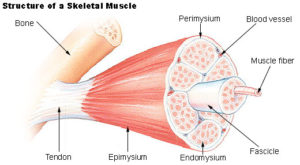

FIBRE TYPE DISTRIBUTION

It has been extensively shown that women possess a greater proportion of type I (slow twitch) muscle fibres (7, 33, 34, 38, 40) and it is no secret that these fibres are more oxidative and take longer to fatigue. In the past, this has been tagged as a negative thing, due to everyone focusing on reduced power/force output and not being able to be as explosive. And, it is true. Research has shown that women cannot recover as fast from explosive, power based repeated efforts such as maximal velocity sprinting (9). However, is this always a bad thing?

People tend to condemn type I muscle fibres with the idea that because they don’t produce as much force as type IIa/b fibres, that they are inferior and that those who possess more type I muscle fibres should stick to endurance sports like running. Since when was it a bad thing to have a higher work capacity? When considering using strength as a means of improving health and even performance, type I muscle fibres can still produce force and can still grow in response to resistance training (37).

As mentioned above, muscle fatigability is a primary vehicle for overload and adaptation. This is the sole reason that most resistance training programs involve a GPP/Strength Endurance/Hypertrophy block or whatever you want it to call. To increase your work capacity and can deal with greater volumes of overload work further down the line. Therefore, women, you have a physiological benefit and are starting at a higher work capacity from the get go.

Plus, we know that fibre type alteration is a common response to exercise (36), so you don’t have to settle for what you start with!

BLOOD FLOW TO MUSCLE TISSUE

This section refers to the circulatory system and how it results in decreased fatigue and potentially explains the improved recovery rates. To begin with, research has previously shown that women tend to possess a greater capillary density per unit of skeletal muscle when compared to men (33).

In addition, during resistance training, females express reduced mechanical compression on blood vessels supplying oxygen and other essential metabolic products as well as improved vasodilation (19, 20, 31), which largely contributes to fatigue resistance.

This essentially means that during exercise, muscle tissue within females is essentially being supplied with more blood. It also means that the removal of metabolic waste-products and CO2 occurs more efficiently, delaying the onset of fatigue even further.

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND MYTHS

OESTROGEN

Many people believe that testosterone reigns supreme and anyone with more oestrogen is incapable of building muscle. However, recent research has found oestrogen to have an anabolic effect on muscle, primarily by lowering protein turnover and enhancing sensitivity to resistance training (16).

Studies have found oestrogen to be key in the activation and proliferation of satellite cell numbers (essential for muscle growth) in regenerating skeletal muscle tissue (11, 39). It has also been found to be highly effective at preventing muscle strength loss in aging females (4).

Studies have found oestrogen to be key in the activation and proliferation of satellite cell numbers (essential for muscle growth) in regenerating skeletal muscle tissue (11, 39). It has also been found to be highly effective at preventing muscle strength loss in aging females (4).

Whilst it remains unclear as to what extent oestrogen has an influence, and what levels are deemed optimal, we cannot condemn this hormone as the enemy of muscle growth and strength!

MENSTRUAL CYCLE

Now this is largely going to be open to individuality obviously. Women have and always will respond differently during their menstrual cycle. However, it is important to note what the research has to say. Whilst this may come as good or bad news to some females, studies have shown no differences in strength and/or fatigability across the whole of the menstrual cycle (10, 12, 18, 26) on a physiological level. However, it has been well documented that motivation and psychological profile on a day to day basis can affect your strength. Therefore, it depends on how you respond as to whether you can train at the same intensity, but note that on a physiological level, your body possesses the same ability at any stage of the month!

SUMMARY

All in all, women are in a greater situation for developing strength and muscle, people just don’t think or know it. Most people use the phrase, “Women don’t have testosterone so can’t build muscle”. I admit I used to think the same (unfortunately). However, the research simply disagrees. Women possess significant ability to increase muscle size and strength. And so they should! Without turning this into a debate, too many women are afraid of lifting weights and too many people project their own opinions on the idea of a muscular female. Take note, being muscular doesn’t mean you will look like a bodybuilder. Far from it. I don’t think people realise how many thousands of hours it takes for bodybuilders to look the way they do.

If women don’t want to become muscular then fair enough, I don’t recommend it or discourage it. I’m neutral. However, when it comes to strength training, I think everyone (not just women) but everyone should be actively seeking to increase their strength. For the purposes of this article (and the one before) I have emphasised women due to frustration on how women avoid weight training entirely. The reason behind this I’m not sure, but the concept of developing one’s physical capacity is a natural tendency, you shouldn’t be avoiding it!

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

After sifting through the research, there are a few points that can be drawn on how women/coaches of female athletes should structure their training:

- More reps and sets/overall volume.

- More frequent training (potentially training twice a day if possible).

- Able to perform high intensity strength workouts more frequently.

- Lower volumes of power based training.

- Emphasis on developing muscle mass through bodybuilding style movements.

REFERENCES

- Adams, G.R.,Cheng, D.C., Haddad, F. & Baldwin, K.M. 2004. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy in response to isometric, lengthening, and shortening training bouts of equivalent duration. J Appl Physiol, 96, 1613–1618.

- Anonymous2010. Putting gender on the agenda. Nature, 465, 665.

- Beery, A.K.& Zucker, I. 2011. Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 35, 565–572.

- Brown, M. (2013). Estrogen Effects on Skeletal Muscle. InIntegrative Biology of Women’s Health (pp. 35-51). Springer New York

- Burd, N.A.,Andrews, R.J., West, D.W., Little, J.P., Cochran, A.J., Hector, A.J., Cashaback, J.G., Gibala, M.J., Potvin, J.R., Baker, S.K. & Phillips, S.M. 2012. Muscle time under tension during resistance exercise stimulates differential muscle protein sub-fractional synthetic responses in men. J Physiol 590, 351–362.

- Cahill, L.2012. A half-truth is a whole lie: on the necessity of investigating sex influences on the brain. Endocrinology 153, 2541–2543.

- Carter, S.L.,Rennie, C.D., Hamilton, S.J. & Tarnopolsky, , 2001b. Changes in skeletal muscle in males and females following endurance training. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 79, 386–392.

- Clark, B.C.,Manini, T.M., The, D.J., Doldo, N.A. & Ploutz-Snyder, L.L. 2003. Gender differences in skeletal muscle fatigability are related to contraction type and EMG spectral compression. J Appl Physiol 94, 2263–2272.

- Dent, J. R., Edge, J. A., Hawke, E., McMahon, C., & Mündel, T. (2015). Sex differences in acute translational repressor 4E-BP1 activity and sprint performance in response to repeated-sprint exercise in team sport athletes.Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(6), 730-736.

- Ettinger, S.M.,Silber, D.H., Gray, K.S., Smith, M.B., Yang, Q.X., Kunselman, A.R. & Sinoway, L.I.1998. Effects of the ovarian cycle on sympathetic neural outflow during static exercise. J Appl Physiol 85, 2075–2081.

- Enns, D. L., & Tiidus, P. M. (2010). The influence of estrogen on skeletal muscle.Sports Medicine, 40(1), 41-5

- Friden, C.,Hirschberg, A.L. & Saartok, T. 2003. Muscle strength and endurance do not significantly vary across 3 phases of the menstrual cycle in moderately active premenopausal women. Clin J Sport Med 13, 238–241.

- Guenette, J.A.,Romer, L.M., Querido, J.S., Chua, R., Eves, N.D., Road, J.D., McKenzie, D.C. & Sheel, A.W. 2010. Sex differences in exercise-induced diaphragmatic fatigue in endurance-trained athletes. J Appl Physiol 109, 35–46.

- Häkkinen, K. (1991). Force production characteristics of leg extensor, trunk flexor and extensor muscles in male and female basketball players.The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 31(3), 325-331.

- Häkkinen, K., & Kallinen, M. (1994). Distribution of strength training volume into one or two daily sessions and neuromuscular adaptations in female athletes.Electromyography and clinical neurophysiology, 34(2), 117-124

- Hansen, M., & Kjaer, M. (2014). Influence of sex and estrogen on musculotendinous protein turnover at rest and after exercise.Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 42(4), 183-192

- Hartman, M. J., Clark, B., Bemben, D. A., Kilgore, J. L., & Bemben, M. G. (2007). Comparisons between twice-daily and once-daily training sessions in male weight lifters.International journal of sports physiology and performance, 2(2), 159.

- Hoeger Bement, M.K.,Rasiarmos, R.L., Dicapo, J.M., Lewis, A., Keller, M.L., Harkins, A.L. & Hunter, S.K. 2009a. The role of the menstrual cycle phase in pain perception before and after an isometric fatiguing contraction. Eur J Appl Physiol 106, 105–112.

- Hogarth, A.J.,Mackintosh, A.F. & Mary, D.A. 2007. Gender-related differences in the sympathetic vasoconstrictor drive of normal subjects. Clin Sci 112, 353–361.

- Hunter, S.K.& Enoka, R.M. 2001. Sex differences in the fatigability of arm muscles depends on absolute force during isometric contractions. J Appl Physiol 91, 2686–2694.

- Hunter, S.K.2009. Sex differences and mechanisms of task-specific muscle fatigue. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 37, 113–122.

- Hunter, S.K.,Critchlow, A., Shin, I.S. & Enoka, R.M. 2004c. Men are more fatigable than strength-matched women when performing intermittent submaximal contractions. J Appl Physiol 96, 2125–2132.

- Hunter, S.K.,Ryan, D.L., Ortega, J.D. & Enoka, R.M. 2002. Task differences with the same load torque alter the endurance time of submaximal fatiguing contractions in humans. J Neurophysiol88, 3087–3096.

- Hunter, S.K.,Schletty, J.M., Schlachter, K.M., Griffith, E.E., Polichnowski, A.J. & Ng, A.V. 2006b. Active hyperemia and vascular conductance differ between men and women for an isometric fatiguing contraction. J Appl Physiol 101, 140–150.

- Hunter, S.K.,Thompson, M.W., Ruell, P.A., Harmer, A.R., Thom, J.M., Gwinn, T.H. & Adams, R.D.1999. Human skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2 + uptake and muscle function with aging and strength training. J Appl Physiol 86, 1858–1865

- Janse de Jonge, X.A.,Boot, C.R., Thom, J.M., Ruell, P.A. & Thompson, M.W. 2001. The influence of menstrual cycle phase on skeletal muscle contractile characteristics in humans. J Physiol 530, 161–166.

- Judge, L. W., & Burke, J. R. (2010). The effect of recovery time on strength performance following a high intensity bench press workout in males and females.International journal of sports physiology and performance, 5, 184-196

- Kim, A.M.,Tingen, C.M. & Woodruff, T.K. 2010. Sex bias in trials and treatment must end. Nature465, 688–689.

- Miller, V.M.2012. In pursuit of scientific excellence: sex matters. J Appl Physiol 112, 1427–1428.

- Munn, J.,Herbert, R.D., Hancock, M.J. & Gandevia, S.C. 2005. Resistance training for strength: effect of number of sets and contraction speed. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37, 1622–1626.

- Parker, B.A.,Smithmyer, S.L., Pelberg, J.A., Mishkin, A.D., Herr, M.D. & Proctor, D.N. 2007. Sex differences in leg vasodilation during graded knee extensor exercise in young adults. J Appl Physiol 103, 1583–1591.

- Pincivero, D.M.,Gandaio, C.M. & Ito, Y. 2003. Gender-specific knee extensor torque, flexor torque, and muscle fatigue responses during maximal effort contractions. Eur J Appl Physiol 89, 134–141.

- Porter, M.M.,Stuart, S., Boij, M. & Lexell, J. 2002. Capillary supply of the tibialis anterior muscle in young, healthy, and moderately active men and women. J Appl Physiol 92, 1451–1457.

- Roepstorff, C.,Thiele, M., Hillig, T., Pilegaard, H., Richter, E.A., Wojtaszewski, J.F. & Kiens, B. 2006. Higher skeletal muscle alpha2AMPK activation and lower energy charge and fat oxidation in men than in women during submaximal exercise. J Physiol 574, 125–138.

- Russ, D.W.& Kent-Braun, J.A. 2003. Sex differences in human skeletal muscle fatigue are eliminated under ischemic conditions. J Appl Physiol 94, 2414–2422.

- Staron, R. S., et al. “Skeletal muscle adaptations during early phase of heavy-resistance training in men and women.”Journal of applied physiology3 (1994): 1247-1255.

- Staron, R.S.,Hagerman, F.C., Hikida, R.S., Murray, T.F., Hostler, D.P., Crill, M.T., Ragg, K.E. & Toma, K. 2000. Fiber type composition of the vastus lateralis muscle of young men and women. J Histochem Cytochem 48, 623–629.

- Velders, M., & Diel, P. (2013). How sex hormones promote skeletal muscle regeneration.Sports medicine, 43(11), 1089-1100.

- Welle, S.,Tawil, R. & Thornton, C.A. 2008. Sex-related differences in gene expression in human skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE 3, e1385.

- Yoon, T.,Keller, M.L., De-Lap, B.S., Harkins, A., Lepers, R. & Hunter, S.K. 2009b. Sex differences in response to cognitive stress during a fatiguing contraction. J Appl Physiol 107, 1486–1496.

- Zucker, I.& Beery, A.K. 2010. Males still dominate animal studies. Nature 465, 690.