Without a doubt the most underrated, misunderstood and often ignored principle of an effective fitness program. Sure, focus on the “optimal” of everything, but completely neglect the idea of how strength and conditioning fits into the logistics of life. Whether you’re an athlete or average gym goer, training is supposed to improve the quality of your life…not detract from it.

The idea that many people state that their lack of results is purely down to “not having enough time” is absurd. I have literally been in a scenario whereby an old friend and I were discussing how someone we knew had recently won a women’s figure competition; whilst studying and graduating with a 1st class Honours Degree from University. Now, my friend said, “I would love to look like that, but I just don’t have the time”.

Whilst we were sat in the pub…and had been for two hours on a Thursday evening.

That was one of the turning points for me and my work ethic, realising that people complain about a lack of time because they have it in their minds that it takes hours and hours to improve their physique and athleticism. You might also think the same. But you couldn’t be more wrong…

PRIORITIES

“It is vain to do with more what can be done with fewer” – William of Occam.

What is more important to you…Spending time in the gym doing bicep curls or spending time with your friends, family, business? If you say the former 100% of the time, then I suggest you reassess where your priorities lie. You don’t get any extra brownie points for getting the same results as one person, having spent twice the time in the gym.

WHAT IS TRAINING ECONOMY?

Training economy refers to the concept of gaining the maximal amount of results, in the shortest time possible and doing the least work required. Many coaches, including the great Joe DeFranco, may argue that this is one of the most important principles in the development of an effective fitness program.

COACHES AND TRAINERS AMONG US

You should keep in mind, that depending on your business model or how you work with clients (that’s down to you), but people (athletes and the public alike) are evidence based individuals. They want results and you must provide that. But stomping your foot and saying, “It would work if we worked together more, so pay up” is rarely going to work.

Instead, part of your job is to evaluate the time you have and choose the biggest “bang for your buck” exercises to include within the fitness program.

Enough of the leg extensions and isolating the upper ubulus maximus diagonalis muscle (not actually a thing by the way). Not only does the client/athlete possess limited desire for how intelligent you appear to them within the session, you don’t have the luxury of the elusive thing: time. On most occasions, you’ll have an hour or two a week.

Working with athletes carries the same issues. In an ideal scenario, you could monitor every aspect of the athlete’s life and make minor adjustments to every aspect of their daily life to optimise the results. Real world? You would be lucky to get 2 hours a week with some athletes/teams.

I’ve worked in clubs/facilities where I was literally given athletes for 30 minutes a session before they went on to do their “technical” work. I know of strength and conditioning coaches who are given 4 minutes. Yes. FOUR minutes to provide an adequate warm up for athletes prior to a game.

Time is a luxury; not something you always have in abundance.

SUBTRACT BEFORE YOU ADD

The biggest issue with training and the whole of the fitness industry nowadays, is that everyone is obsessed with adding the newest trick or exercise that promises newfound gains. Whilst I’m all for trying to continually seek the answers and improve on what we already have, you would be much better to stick with the tried and tested methods to form the core of your training program, then look to experiment later.

Or continually add in new things and gamble with your most valuable resource: time. The choice is yours.

Instead, I urge you to just do a quick 80:20 Analysis of your current fitness program, based off a simple concept of Pareto’s Law. Find the 20% of the work that is bringing about 80% of your results, and don’t worry (or completely discard) the rest.

“Perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but then there is nothing left to take away” – Antoine de Saint-Exupery. This couldn’t be more true when looking to construct an effective fitness program.

Look to your fitness program and ask yourself one of many simple questions…

How much time do you spend on machines/cables vs. how much time you spend with a barbell and free weights?

As you will read shortly, this is one of the reasons your “results” take such a long time to achieve. Before you read ahead, don’t think of what you’re going to add to your training. First, take away the exercises that aren’t worth your time.

HOLD YOUR HORSES

Now…I must preface this by saying, this is entirely contextual. There will be many bodybuilding purists that will swear by certain exercises and the idea that the development of muscle mass is something everyone should pursue. To be fair, they wouldn’t be wrong.

However, we are referring to the greatest results in performance adaptations (strength, power, longevity and health), in the shortest time possible.

1) IGNORE ISOLATION, DEVELOP “COMPOUND INTEREST”

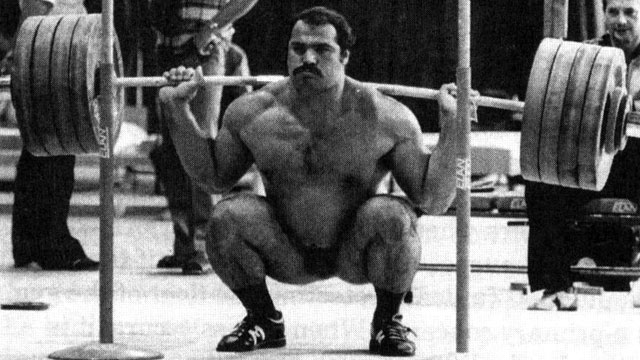

Whilst isolation exercises have their place and are great for focusing on imbalances and lagging body parts, when looking to get the biggest “bang for your buck”, your time is better well spent on the “larger” movements. The amount of people I see performing leg presses and leg extensions but shy away from the squat rack is quite frankly depressing. Simply because it takes a little longer to learn/teach (this largely depends on your ability as an athlete/coach), people “can’t be bothered”.

Although there is research to suggest a similar hypertrophic/muscle growth response within single and multi-joint exercises, the methodology is flawed and lends support to the use of multi-joint exercises anyway. Gentil (4) found that performing a multi-joint exercise involving the biceps (lat pulldowns) compared to a single joint (bicep curl) resulted in the same hypertrophic response in the biceps…but in the multi-joint group you gained additional benefit by stimulating a whole host of other muscles involved, right?

In addition, research comparing the squat and leg extension found similar muscular recruitment. However, they only measured muscular recruitment of the quadriceps. Again, the squat will help develop the glutes, spinal erectors and a whole host of other muscles, not to mention the efficacy of using the squat to develop sprint speed and jump height (1, 7).

In addition, recent research has found that adding single joint isolation exercises to a training session following the completion of compound exercises, provides little to no extra benefits (3) and when comparing squats versus leg presses research has found a greater release of testosterone and growth hormone when performing the squat (6).

2) SUPER-SETS

Instead of resting for 3 minutes between sets, then 3 minutes between exercises etc. Combine two together and perform them back to back. Now, be careful…I would be inclined to say that you should avoid this with the more mechanically demanding compound exercises (e.g. squats, bench press etc.) and use it for the “easier” compound exercises (e.g. dumbbell press, pullups etc.). It’s also a good way to get (and keep) the heart rate up without doing dreaded cardi-no within your fitness program

In addition, super-setting has been found to increase energy expenditure and excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC) and may benefit individuals attempting to increase exercise volume and energy expenditure with limited time (5).

3) GO FULL BODY

If you truly want to optimise your progress and get the most out of the least, stop basing your training days off a traditional bodybuilding split, whereby you only train chest once a week and legs another. On top of countless physiological reasons why this is one of the least productive ways to make gains, you are limited in what adaptation you can cause within one training session. Using a hypothetical example:

Monday = Chest Day (World-wide).

You plan for Wednesday to be your leg day. But something comes up and you can’t make it to the gym until the weekend (when you planned to do back). Do you train your back or your legs in that scenario? Or do you put both of those sessions together and just stay in the gym for 3-4 hours to “get it done”.

You plan for Wednesday to be your leg day. But something comes up and you can’t make it to the gym until the weekend (when you planned to do back). Do you train your back or your legs in that scenario? Or do you put both of those sessions together and just stay in the gym for 3-4 hours to “get it done”.

No. Instead, you could have (on the Monday) trained 1-2 chest exercises, then performed some squats and a rowing variation. You would have covered most of your large muscle groups and (if you miss a session due to unforeseen circumstances, it’s not the end of the world).

Recent research compared a full body routine to traditional “split training” fitness program. They not only found similar strength adaptations for both groups, but they also found a greater reduction in body fat with the full body training group (2). Which would you rather have?

USEFUL LINKS:

- Joe DeFranco – Training Economy = https://www.defrancostraining.com/training-economy-how-to-maximize-efficiency-in-the-gym/

- Strength Forge 5 Key Strength Exercises = https://www.strength-forge.com/articles/strength/key-strength-exercises-structure-workout/

REFERENCE LIST

- Chelly, M. S., Fathloun, M., Cherif, N., Amar, M. B., Tabka, Z., & Van Praagh, E. (2009). Effects of a back squat training program on leg power, jump, and sprint performances in junior soccer players.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(8), 2241-2249

- Crewther, B. T., Heke, T. O. L., & Keogh, J. W. (2016). The effects of two equal-volume training protocols upon strength, body composition and salivary hormones in male rugby union players.Biology of sport, 33(2), 111.

- Gentil, P., Soares, S. R. S., Pereira, M. C., Cunha, R. R. D., Martorelli, S. S., Martorelli, A. S., & Bottaro, M. (2013). Effect of adding single-joint exercises to a multi-joint exercise resistance-training program on strength and hypertrophy in untrained subjects.Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 38(3), 341-344

- Gentil, P., Soares, S., & Bottaro, M. (2015). Single vs. multi-joint resistance exercises: effects on muscle strength and hypertrophy.Asian journal of sports medicine, 6(2)

- Kelleher, A. R., Hackney, K. J., Fairchild, T. J., Keslacy, S., & Ploutz-Snyder, L. L. (2010). The metabolic costs of reciprocal supersets vs. traditional resistance exercise in young recreationally active adults.The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(4), 1043-1051.

- Vingren, J. L. (2012).Hormonal response to free weight and machine weight resistance exercise (Doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas).

- Wisløff, U., Castagna, C., Helgerud, J., Jones, R., & Hoff, J. (2004). Strong correlation of maximal squat strength with sprint performance and vertical jump height in elite soccer players.British journal of sports medicine, 38(3), 285-288