The revolution is finally here. It’s been happening slowly but surely over the past few years and hopefully, will continue. Women aren’t only peeking over to the dumbbells, but instead, weightlifting for women is becoming a go-to form of training. The methods of “high reps, low weight” are (thankfully) slowly dying and being replaced with the principles of strength and power training.

However, there is still a large percentage of people (men and women included) who are unconvinced of the benefits and almost necessity of weightlifting for women.

“I’ll look masculine.”

“I don’t want to be bulky.”

“Doesn’t light weight, high reps tone your muscles?”

Each of these comments (and many more besides) are commonplace in a gym setting and need to be removed and forbidden as soon as possible. Because ladies, you need to be lifting weight! And heavy weight at that!

This article will hopefully convince you of the reasons why weightlifting for women is essential.

Part 2 will follow, with how it should be done.

But as with most things explanation precedes application.

So let’s get started on a few reasons why weightlifting for women is so important!

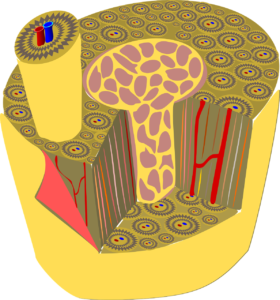

1. BONE HEALTH

Unfortunately, a variety of lifestyle/nutritional factors and decreases in oestrogen in women with age (7), often results in a condition known as osteoporosis. This is marked decrease in bone mineral density, that leaves the individual prone to an increased risk of stress fractures and osteoarthritis (8). Whilst age is a large factor, want to know the one way this can be prevented/remedied?

Strength training. That’s right. Research has extensively shown that bone tissue becomes more dense and stronger as a long term adaptation to resistance training (5, 9, 10, 12). And better yet, this is not gender or age specific. Most of the research has actually been conducted on women, due to the higher prevalence of osteoporosis, lending more than enough evidence to suggest that weightlifting for women is more important than ever.

Also note, that whilst a lot of the research has been conducted on elderly women/populations, the process of heavy loading throughout life will lead to prevent this condition from occurring.

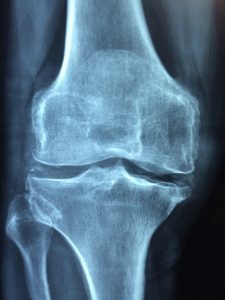

2. JOINT HEALTH

Let’s face it. How many times have you heard, lifting weights is bad for your joints? If you’ve been training at the gym and you pick up a joint issue, people will immediately state something along the lines of, “That’s because you’re lifting weights”.

You want to know what else is bad (actually worse) for joint health? Sitting at a desk, remaining inactive for 40-50 years of your life. So what can we do?

Weightlifting for women (and men for that matter) has been shown to favourably modify connective tissue and actually improve joint health (17), providing that the intensity of loading is high to stimulate collagen synthesis.

So where does the knowledge of lifting being bad for your joints come from? Misconceptions and misinformation.

No exercise is inherently dangerous, how you perform it is.

3. RISK OF INJURY

Within the female population, there are several complications with joint health that could be avoided by strength training. Hyper-mobility of the lumbar spine (lower back) is all too common. Whilst this may be down to individual anthropometry, it is largely dependent upon society encouraging women to adopt a lordotic, ‘feminine’ posture. This leads to poor trunk angle control and an inability to stabilise the position of your torso (2, 14). Whilst previous speculation surrounding severe injuries (e.g. ACL ruptures) was based on physiological factors such as pelvic width and intercondylar notch width (the gap in which the ACL lies), recent research has found a weak correlation between these factors and rates of ACL ruptures (1). They and other researchers have found that other factors such as muscular strength may play a more significant role (16).

How can these injuries be prevented?

Answer: Strength Training (combined with correct movement mechanics).

What’s one of the main differences between male and female sport?

Answer: A lack of strength training in female sport.

4. DEVELOPING CORRECT MOVEMENT

As mentioned above, strength training not only has the capacity to strengthen connective tissue within/surrounding the joint, but it also provides the foundation for developing correct and efficient movement patterns that are performed in everyday life and out on the field. For example, teaching someone how to squat safely, has high sporting transfer and benefits to jumping performance and can decrease injury risk.

Whilst power training is great, one aspect in which people’s form tends to breakdown is the velocity of the movement, and you would be surprised how much of a breakdown may occur. Yes, weight can result in form breakdown, but there are also other methods of increasing strength without simply always adding weight to the bar.

5. ‘TONING’/DEFINITION

First of all, muscle tone refers to the level of neural innervation within a muscle. It has nothing to do with the way the muscle looks, so please can we stop using it? Muscular definition on the other hand is referring to the aesthetic look of a muscle and is therefore more appropriate. This refers to the combination of reducing body fat and increasing muscle mass of a given body part.

However, in females (despite what the media may have you believe), having low body fat levels can result in a serious health condition often termed the “female athlete triad”. This is a combination of hormone/menstrual irregularities, disordered eating and low bone mineral density (as mentioned earlier) (3, 15).

For women to be within a “healthy” range, they must have more body fat compared to men. As a general guideline, going below 15% body fat can result in negative symptoms occurring.

So, out of the equation mentioned above, all we have left to do (as well as minimising body fat within a healthy range), is to alter the muscle mass within a given region of the body. How can this be done? Surprise, surprise…Strength Training.

6. ENDURANCE AND SPORT

Although this section could take up a whole article within itself, in addition to the numerous factors mentioned above, strength is well-known to be the foundation upon which all other components of performance such as power are developed (4). Strength training has also been found to have a direct effect on improving performance across a variety of tasks in endurance (6, 8) and team-based sports (11).

SUMMARY

- Strength training in females is just as effective as it is in male populations.

- Hormones and age have a negative effect on bone health. Resistance training can be highly effective to prevent symptoms occurring by increasing bone mineral density.

- Strength training has been shown to be effective at reducing injury risk in females.

- “Toning” refers to nervous activity within a muscle, not the way it looks.

- The muscular definition refers to aesthetic appearance, including decreased body fat and increased muscle mass.

- Due to significantly low body fat levels (less than 15%) having negative implications on hormone function and body systems, the focus should be on training the muscular component.

- Strength training has been shown to be highly effective at improving sporting performance within females.

- NO EXCUSES. The long term benefits of resistance training are unmatched and therefore should be included within your training.

Look out for Part 2, in which we discuss HOW weightlifting for women should be done and if there are any differences from the “general recommendations”.

REFERENCE LIST

- Anderson, A. F., Dome, D. C., Gautam, S., Awh, M. H., & Rennirt, G. W. (2001). Correlation of anthropometric measurements, strength, anterior cruciate ligament size, and intercondylar notch characteristics to sex differences in anterior cruciate ligament tear rates. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 29(1), 58-66.

- Balali, (2014). Comparison of Postural Control and Core Endurance in Young Females with and Without Hyperlordosis. Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 1(2), 109-128.

- Cobb, K. L., Bachrach, L. K., Greendale, G., Marcus, R., Neer, R. M., Nieves, J., … & Tanner, H. K. (2003). Disordered eating, menstrual irregularity, and bone mineral density in female runners. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 35(5), 711.

- Cormie, P., McGuigan, M. R., & Newton, R. U. (2010). Influence of strength on magnitude and mechanisms of adaptation to power training. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 42(8), 1566-81.

- Heinonen, A., Oja, P., Kannus, P., Sievanen, H., Haapasalo, H., Mänttäri, A., & Vuori, I. (1995). Bone mineral density in female athletes representing sports with different loading characteristics of the skeleton. Bone, 17(3), 197-203.

- Hoff, J., Helgerud, J., & Wisloeff, U. L. R. I. K. (1999). Maximal strength training improves work economy in trained female cross-country skiers. Medicine and Science in sports and Exercise, 31, 870-877.

- Johnell, O. (1996). Advances in osteoporosis: better identification of risk factors can reduce morbidity and mortality. Journal of internal medicine, 239(4), 299-304.

- Johnson, R. E., Quinn, T. J., Kertzer, R., & Vroman, N. B. (1997). Strength training in female distance runners: impact on running economy. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 11(4), 224-229.

- Kelley, G. A., Kelley, K. S., & Tran, Z. V. (2001). Resistance training and bone mineral density in women: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 80(1), 65-77.

- Lohman, T., Going, S., Hall, M., Ritenbaugh, C., Bare, L., Hill, A., … & Pamenter, R. (1995). Effects of resistance training on regional and total bone mineral density in premenopausal women: a randomized prospective study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 10(7), 1015-1024.

- Myer, G. D., Ford, K. R., Palumbo, J. P., & Hewett, T. E. (2005). Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. Journal of strength and conditioning research/National Strength & Conditioning Association, 19(1), 51-60.

- Nichols, D. L., Sanborn, C. F., & Love, A. M. (2001). Resistance training and bone mineral density in adolescent females. The Journal of pediatrics, 139(4), 494-500.

- Panay, N. (2008). Menopause and the postmenopausal woman. Dewhurst’s Textbook of obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 479-95.

- Rijken, N. H. M., van Engelen, B. G. M., de Rooy, J. W. J., Geurts, A. C. H., & Weerdesteyn, V. (2014). Trunk muscle involvement is most critical for the loss of balance control in patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Clinical Biomechanics, 29(8), 855-860.

- Stand, P. (2007). The female athlete triad. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc, 39(10), 1867-82.

- Straub, R. K., Khayambashi, K., Ghoddosi, N., & Powers, C. M. (2015). Hip muscle strength predicts noncontact ACL injury in male and female athletes: a prospective study.Journal of Athletic Training, 50(10), 1103-1104.

- Stone, M. H., & Karatzaferi, C. (2008). Connective tissue and bone response to strength training. Strength and Power in Sport, Second Edition, 343-360.