Don’t have time to read the whole article right now?

No prob. Let me send you a copy so you can read it when it’s convenient for you.

Just let me know where to send it (takes 5 seconds):

Note - you'll also receive our exclusive weekly newsletter to help you on your Journey to Strong, once you've received your guide!

Don't worry, there's no spam and you're free to unsubscribe at any time.

Set the Scene

Through rain, wind and sun, she pushed onwards. Step by step, each time feeling the earth beneath her feet Melissa forged her way through the 26.2 mile course laid out in front of her. Hoping for the best, but always preparing for the worst she had trained leading up to this point with the notion of not only completing a marathon but doing so comfortably.

And by this point…up to 16 miles in, she felt more positive than ever.

Keeping her stride long and her shoulders relaxed, she wondered what all the fuss was about.

Until mile 17.

As the saying goes, she ran into an imaginary brick wall.

Enough to stop anyone in their tracks and call it a day.

Dizziness, feeling faint and unaware of where she actually was…and yet…she carried on forwards.

Step by step, one foot at a time, her legs seemed to continue to carry her.

By mile 18 the feeling of complete exhaustion had left her and, going off her km times, she actually finished the final 2km a full 30 seconds faster than her average.

Whilst others were limping around at the finish line, she walked around as if she had been a spectator the whole time.

How?

One Foot in Front of the Other…

It’s a bucket list thing that many people say they want to do: to take part and complete a full marathon – but few actually get round to it.

Or better yet, thousands of people lace up their shoes and hit the open road with more willpower than they ever knew existed – only to end up hurt and potentially suffer a life-altering injury as a result.

Does it have to be that way?

Do all marathons (or other forms of running for that matter) have to end with battle scars or torturous sensations that would flatten most people for weeks?

The simple answer is…no.

Whether it’s a marathon or simply using running as a method of losing weight –

Strength training for runners is going to be an integral part of your journey.

Today we’re going to discuss why strength training for runners is the key component missing for most when building up to a marathon or any form of running race.

Chapter One – What Is It About Running?

Before we go any further, I’d just like to point out that the majority of this guide on strength training for runners, is tailored towards longer distances. There is a section on short distances, but primarily, we’re concerned with anything 5km and upwards.

WHAT?

Learn the topic.

Masochistic Obsessions

Running has always fascinated me.

Not from a viewpoint as a participant but merely a spectator of the sport and the sense of community it creates.

Although the brotherhood of iron and the lifting community has some of the most devout followers you’ll ever come across, the sport/exercise modality of running holds the mantle of “most participants” by far; surpassing every other sport by several strides (pun intended).

What is it that makes so many people gravitate towards this form of exercise?

Ease of Access + Love/Hate Relationship

Ironically, when asked most people would curl their lip upwards in disgust at the idea of running.

More often than not, I come across people who hate the idea of having to run and yet when they decide they want to “get fit”, it is the first thing they gravitate towards.

Why?

It’s primarily to do, with ease of access.

The primary mission of Strength Forge is to remove all barriers to strength, providing everyone with an understanding of what, why and how to include strength into your life.

Running however, already has those barriers removed.

Simply strap on a pair of shoes (or if you’re part of the barefoot crowd, you don’t even need that!), put one foot in front of the other…and you’re off.

Whilst this is far from optimal, the concept of technique/running efficiency/training plans/peaking/tapering etc. all comes later. For now, just go out, run as far as you can comfortably and go from there.

Not only do you need minimal equipment, but there is virtually no skill involved. As a result, people are more than willing to engage in competition without the fear of embarrassment or loss. You race against others yes, but you primarily race against yourself, whilst enjoying the company of others.

The barrier of entry to running is non-existent, as a result - it's the go to exercise choice for most of the general population.

This means that the competitions that take place such as local 10k, right through to the London Marathon are usually packed full, particularly when compared to other sports.

When looking at the numbers, the results are staggering, taken from runnersworld.com…

To register for the 2020 race, runners had to submit their application this month—and there was no shortage of interest this year. According to a news release from the London Marathon, 457,861 applicants registered for a spot on the ballot for 2020, which was more than a 10 percent increase from last year (414,168 applied for the 2019 race).

Just re-read that again.

That’s 457,000+ people that applied to run a marathon. Not just jog around the local park, but to compete in a 26.2-mile running race.

And within that race, there is a range of experience levels, from recreational runners – right the way through to the greatest in history, the almighty Kipchoge.

So where does strength training for runners fit into this recipe?

Born 2 Run

You see, in the process of evolution, Mother Nature granted animals several impressive physical traits – The speed of the cheetah, the power of the lion, the sight of a hawk…but few people mention, the endurance of man.

As a result of thousands of years of selective pressures, we’re up in the big leagues along with horses, sled dogs and other mammals that are capable of covering great distances in one fell swoop.

Several physiological adaptations exist that you might not be aware of – Did you also know that the arch of your foot acts as a springboard to recoil and propel your body forward after each step? (15).

Contrary to what you may think, we’re actually built for this.

If you look a little further, there’s a current debate as to whether we’re subject to evolution in the modern age. The most agreed upon answer seems to be that although we’re not going directly experiencing Darwinian Evolution – selection based off the natural, environmental pressures – we are still exposed to Cultural Evolution – adaptations brought about changes in our collective, cultural behaviour.

And one of the major things we see with Cultural Evolution, is a rapid decline in our physical strength and overall fitness – it’s a well-known fact we’re not as fit as our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

I won’t delve into this topic in too much detail, but it’s becoming increasingly recognised that our decline in health can be attributed to processes known as sarcopenia, the loss of muscle tissue and dynapenia, the loss of strength.

In fact, recent research has attributed the dynapenia to be a key regulator of physical ability for everyone – from the elderly (4, 20, 24) and even in children (10).

In other words – if this is where a huge portion of our physical decline comes from – it means it’s our primary weakness and the main thing we need to work on to stay healthy.

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Interesting Fact!” no=”1/1″]Learning about dynapenia and sarcopenia was the primary motive behind teaching others about the importance of strength training. [/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

There are several factors that contribute to our ability to run and although yes, we should play to our strengths, if you hope to be the best that you can be (and long term, the healthiest version of yourself), strength training for runners is the key to addressing your weaknesses.

Chapter Two – Faults with Traditional Running Training

Whilst this may sound controversial, the current and most popular method of training for a marathon is actually far from optimal for most and can be improved to not only create a more enjoyable experience but increase the likelihood of PBs for experienced runners.

But in order to understand what we need to fix, we first need to understand what’s broken.

So let’s dive into the faults with traditional running and why strength training for runners is the way to go.

1. Too Much Specificity

Let’s take football as the example.

Do you think it would be wise for a footballer to train for football, by simply playing 90-minute games constantly throughout their training week?

Or boxing. Is the best way to train for boxing to keep getting in the ring, gloves on, mouthguard in and standing toe to toe for a full 12 round bout?

No.

Although playing the game is part of the training, it’s far from being the only thing that matters.

There are drills that break down specific components of the skill. There are separate exercises given to the athletes that address weaknesses and condition their body to be best suited for the task at hand.

So, answer this question, why is it that when people sign up to the world of running, all they do is lace up and…well…go for a run?

It’s simple really. As mentioned earlier, there is a such a small barrier to entry (more or less anyone can slap on a pair of running shoes and step outside their front door), that this is the route most choose to take.

However, if you want to keep running and believe it or not, actually enjoy it…strength training for runners is the way to go.

2. Individuality

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Pop Quiz – What is the 3rd Law of Physical Training?” no=”1/1″]Law of Individuality – Tailoring exercise to meet the needs of the person, taking into account:

- Genetics

- Efficiency of Execution

- Enjoyment

- Logistics[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

So why is it, that when starting to run, we simply all do the same form of running program?

The traditional form of running training typically consists of:

- Series of shorter distance runs to start off with.

- Gradually increase the frequency (may be add in 1 or 2 extra runs per week).

- Stabilise the frequency (i.e. around 3x per week) and begin to increase the length of 1 of them.

- Then begin to increase the length of the other two, but still keeping them shorter than the actual long run.

- Finally peak your training distance and then enter a 2-week taper in which the volume drastically reduces, prior to race day.

The primary problem with this method (as effective as it genuinely is), is…

…What works for some, doesn’t work well for others.

Let’s Gain Some Clarity

Look. I get it. The distance you have set out to run, is the same for everyone. So the actual running side of things has to be pretty similar for most people – regardless of what I say.

However, strength training for runners is where the Individuality comes into play.

This is where we can target the weaknesses, we can tailor the specific exercise needs to you as an individual and overall, make you a better runner.

3. Improper Progression + Monitoring

As I’ve written about before, monitoring yourself during an exercise program is one of the most integral aspects of physical training – and it’s no different with strength training for runners.

In the same way, someone trying to lose weight will be defeated if they only focus on what the scales are saying…getting better at running isn’t always about getting faster or running further.

Other factors such as:

- Improved running economy

- Rate of Perceived Exertion (I.E. How difficult did the run feel?)

- Joint Stability and Strength etc.

Are all metrics that strength training for runners should involve, in order to keep you on track to becoming a better runner overall.

4. No Focus on Weaknesses

For most, running comes across as the major weakness. Because it’s tiring, mentally challenging and at the start, relatively difficult many people believe that they simply aren’t “made to run”.

Unfortunately, however, that excuse no longer carries any weight.

Chapter Three – Why Strength Training for Runners is so Important

So now that we understand what’s wrong with traditional training, it’s time to dive into the nuances behind why strength training for runners is essential.

WHY?

Learn the science and theory.

1. Running Economy

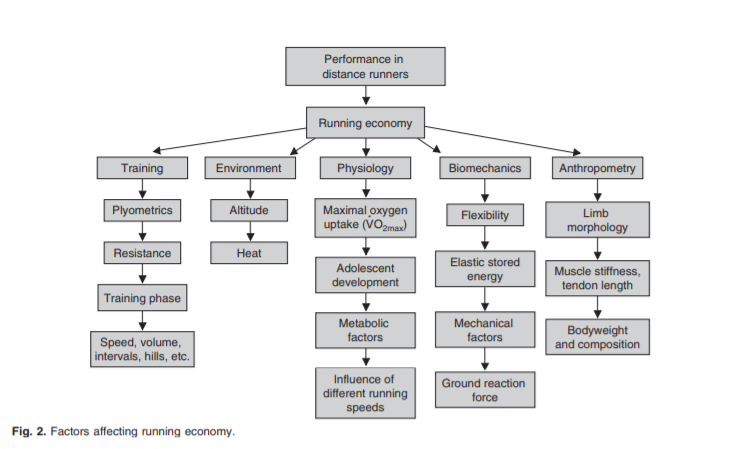

Running economy is something that is often underrated and yet, is one of the biggest factors contributing to success in running. It can be defined as:

The steady-state oxygen consumption (VO2) at a given running velocity, which is often referred to as running economy (5, 6, 25).

Taken from Saunders et al. (2004)

Now, this isn’t going to be a comprehensive breakdown of the mechanics of running, but it’s clear, there’s a lot that goes into being a runner with great running economy.

Too Little, Too Late…Or Is It?

It might be tempting to look at the diagram above and sigh, thinking, “I didn’t have control of adolescent development and certainly can’t change my limb morphology”…fortunately, however, there are several factors that we can influence, through correct training.

General Running Posture

Now, this term is used as a catch-all phrase, grouping together several of the variables above (such as flexibility, tendon stiffness etc.). It essentially refers to the balance of your body’s biomechanics. Are you wasting energy anywhere, or over-relying on some areas more than others?

In general, a lot of people, consider themselves to have bad posture. But when running, postural issues only get worse. Remember, speed is the enemy of control. So as soon as you set off running, it’s not uncommon to see people start to:

- Hunch over…

- Shuffle their feet…

- Droop their heads…

- Twist their body from side to side…

- Swinging the legs out to the side

- Knee valgus

- Ankle pronation.

Thankfully, we can fix most of them through strength training for runners.

Stride Length

Stride length refers to…well…the length of your stride.

And is a directly influenced by how much force your lower body can produce, each time it hits the floor (8).

Research has found running economy to be directly influenced by the coactivation of muscle groups that maintain stiffness in the tendons when the foot hits the ground with each contact (16).

To add to that, one study postulated that the focus on increasing stride length and the timing of muscle activity may lead to improvements in running economy (1).

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Here’s a Handy Lil’ Tip for all You Runners Out There…” no=”1/1″] A great way to tell if your stride length is your weakness is to listen to the sound of your feet. If you’re a shuffler or in other words, you’re lazily pushing the floor away whilst dragging your feet, then you definitely aren’t maximising your stride length and could do with a little more strength. [/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

Strength training for runners directly addresses this problem.

Strength Training For Runners, Makes You a Better Runner

By getting stronger (particularly in your lower body), you provide your body with the necessary neuromuscular arsenal to run for prolonged distances.

This isn’t just supported by theoretical evidence.

There is a plethora of research showing that strength training is an incredibly effective method at improving running ability.

From improving the force production to increasing lactic acid tolerance (3, 13) strength training for runners has been found to be highly effective at increasing performance.

And it’s not exclusive to one type of person.

Studies have found significant improvements in untrained individuals (12, 21, 22), to moderately trained females (14), right through to well-trained triathletes (23).

Strength training for runners is the link you’re missing.

2. Preventing Injuries

If there was one reason, one reason only, that you took up strength training for runners – it’s this one.

Running is an incredibly demanding task on the body. Even though we’re built for it, our bodies aren’t necessarily adapted to run, after spending hours sat at a desk wasting away and eating too much food.

Due to the reasons outlined above, simply getting out onto the road often leaves the community of runners rife with “niggles” and “sprains” and whatever other words you want to use in its place.

And short of gaining a significant injury from a trip or fall, the majority of these injuries are preventable with appropriate strength training for runners.

Muscle strength has been shown to be a strong predictor of several overuse injuries such as:

- Achilles tendinopathy (18)

- Patellofemoral syndrome (2)

- Overall lower body injury rates (7, 17).

3. Carry Your Own Weight

This reason is a rationale for all athletes, and everyone else for that matter, to start strength training.

Think about it logically…your muscles have to carry your skeleton, skin, organs…your entire body. Your body has to physically carry, support and move itself as you go about your daily activities.

Even more of a reason – an overweight person with weak muscles is going to have a hard time moving not only their own body weight but the excess tissue they’re having to carry around.

It’s the equivalent of me handing you a heavy rucksack and telling you to get a shift on.

However, the stronger you become, the lighter that rucksack begins to feel.

You can move and manipulate your own body with greater ease.

Strength training for runners allows you to feel lighter on your feet – skipping along the floor, rather than trudging your feet step by step.

You've come this far...

If you've ran out of time, no worries at all - get the article as a full PDF here.

Chapter Four – Implementing Strength Training for Runners

HOW?

Learn the implementation.

Strength Should Supplement

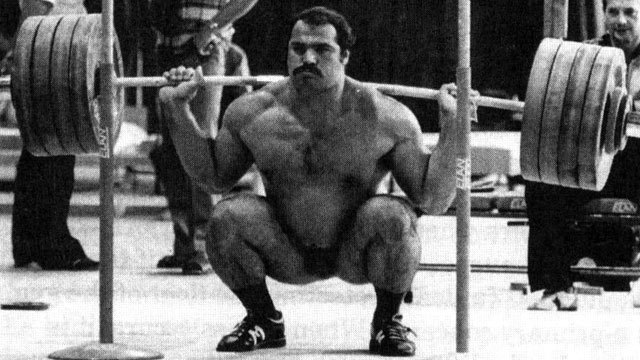

Look, I get it. I’m not trying to use strength training for runners, to make them turn to the dark side and begin powerlifting and strongman.

And this is actually one of the biggest fears for most with strength training for runners. They think that starting lifting weights is going to result in detracting away from running time. Why spend an hour in the gym lifting when I can spend an hour running? (See reasons above)

In the same way, a strength athlete trying to get fit shouldn’t abandon all forms of lifting and begin cardio, strength training for runners shouldn’t involve ditching the running shoes and holistically lifting. There needs to be a balance.

Instead, we add it into your current routine as shown in the example layout below.

Day of the Week | Running | Strength Training |

|---|---|---|

Monday | 3 km (Gym Run) | Core, Isolation and Upper Body |

Tuesday | - | - |

Wednesday | 5 km (Outdoor) | - |

Thursday | - | Lower Body + Core |

Friday | - | - |

Saturday | 10 km (Outdoor) | - |

Sunday | - | Lower Body + Isolation |

Build Your Base

Compound movements are much more important to develop overall strength, however, that’s not to say that strength training for runners doesn’t utilise some isolation exercises to their full effect.

As discussed in | The Ultimate Guide to Strength Training for Beginners |, there are 8 key movement archetypes that the human body should be able to perform under load.

Primarily, in strength training for runners, we want to be focusing on:

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Squat” no=”1/1″]The squat – a staple of any lower body strength training program.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Hip Hinge” no=”1/1″]The hip hinge is the key to developing the strongest version of yourself – it’s a paramount movement for strength training.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Loaded Carries” no=”1/1″] For all that there is in the world of exercise, our neuro-muscular system is orchestrated for one primary role: Walking.

[/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

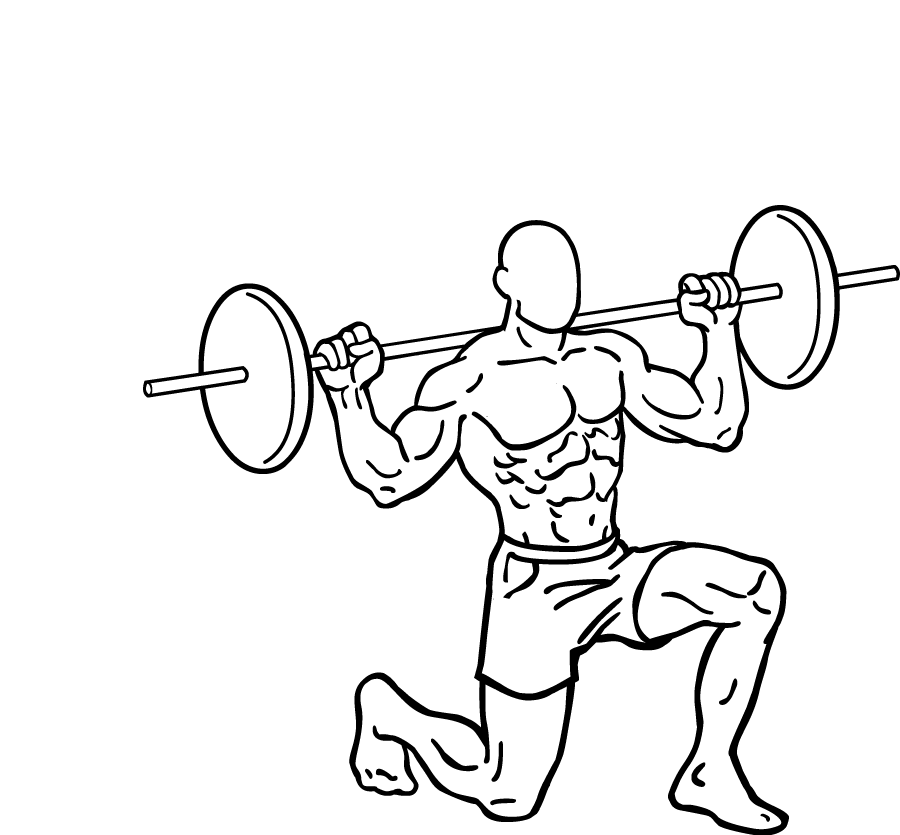

[thrive_toggles_group”][thrive_toggles title=”Lunges/Unilateral Work” no=”1/1″]

The lunge pattern is essential to build coordination, core control and stability – there’s no use having a strong squat if you can’t even balance on one leg. [/thrive_toggles][/thrive_toggles_group]

Strength training for runners should involve the above movements and their variations, such as the example table given below:

Lower Body | Acute Training Variables (Reps, Sets etc.) |

|---|---|

Hinge = Sumo Deadlift | 3 sets of 5 reps (Progressing to 5 sets of 3 reps) |

Squat = Goblet Squat | 3 sets of 8 reps (Progressing to 4 sets of 6 reps) |

Loaded Carries = Farmers Walks | 3 sets of 20 secs (Progressing to 4 sets of 60 secs) |

Unilateral Exercises = Split Squats | 4 sets of 6 reps (Progressing to 3 sets of 12 reps) |

Now that’s not to say that upper body exercises aren’t valid, as you can see with the infamous Sir Mo Farah performing back squats and a few upper body movements in the video below:

Main Aims of Strength Training for Runners

Now, the nitty gritty reason for the progressions for each could take a while (if you’re interested, you’re more than welcome to leave a comment below), but note that when strength training for runners, we should have 3 primary outcomes:

- Bulletproof the Body – Prevent Injuries from Occurring:

This involves strengthening connective tissue, improving motor pattern efficiency (i.e. how well you move) and keeping the body healthy.

- Maximise Relative Strength Gains

This refers to increasing strength, without gaining massive amounts of muscle – click here if you want to learn more about how to forge strength without size.

- Improve running times

To all of the runners out there, this is the main one. Otherwise, what’s the point?

Acute Variables – Reps, Sets and Load

We know the Laws of Physical Training:

Component Specific Progression, Best Suited to the Individual.

However, the acute variables are the small things that determine the direction in which your progression goes. In other words, higher rep ranges tend to lead to greater muscular endurance and lower repetition ranges tend to build maximal strength.

Now, in strength training for runners, most people would immediately assume that we want higher repetition ranges to build muscular endurance.

However, this isn’t always the best idea.

And here’s why…

What Are You Working For?

Muscular endurance is an essential aspect of running performance. That’s kind of an obvious fact.

However, the involvement of the muscle is largely dependent upon the distance you’re running. If you’re running really long distances (relative to the individual such as 10km plus), the muscles don’t actually contribute as much as people think.

Referring back to running economy, the actual process of running is so efficient within the human body, that we rely heavily on tendon stiffness and the recycling of gravitational/kinetic energy to propel us forward.

Let’s take a look at the Olympics…

The shorter the distance the athlete covers, the more muscular they tend to be – and vice versa.

What Distance Are You Covering?

This is probably one of the most distinguishing factors that will determine how we program the strength training for runners.

We know that it’s recommended, and the movements listed above are crucial to build the strongest body you can have – but what about the number of reps, sets, load and other variables that contribute to programming.

Shorter Distances = Below 1500m

The shorter the distance being covered, the more lactate based the activity.

In other words, the more we’re requiring energy to be produced in the absence of oxygen – fortunately, this is something that can be trained.

You’re also looking at faster running speeds for most, meaning we need to focus on power.

In other words, the strength training for runners should be centred around building maximal strength (there’s never a downside to this), then utilising explosive tasks, with shorter rest intervals to build lactate tolerance.

Now without causing too much confusion, these fitness components can overlap and also contradict one another in their development.

For example, the production of lactic acid during training has been shown to negatively influence power output in a variety of tasks due to potentially interfering with neural feedback (9, 11).

In other words, you’ll have to be savvy in your methods of structuring them in your training.

Going back to strength training for runners…the argument for building muscular endurance is a sound one, but it shouldn’t be the only thing that is developed – maximal strength is essential.

Not only does the complexity of the exercise influence how many reps should be done with each exercise but higher rep ranges can also lead to stimulating a hypertrophic (muscle building) response. Excess muscle tissue isn’t necessarily something you want as it increases the oxygen consumption when running which can actually increase the energy cost of running (19).

This isn’t always the case, but it’s not rare to see “strength training for runners” involving the all too common – 3 sets of 10 repetitions, which also happens to be the same recommendations for bodybuilding.

Finding Balance – Max Strength and Muscular Endurance

So… just to recap, we want to build maximal strength for the reasons outlined above:

- Improve running economy due to greater tendon stiffness, improved flexibility, stride length etc.

- Preventing Injuries – stronger, stiffer tendons are more resilient ones.

- Ability to carry one’s bodyweight.

But we also want muscular endurance in certain areas to make sure our body’s don’t give up after the first 300 yards.

So how is it done?

Strength training for runners should aim to do 3 things: 1) Bulletproof the Body (2) Max Relative Strength (3) Improve Running Times...otherwise what's the point?

Isolation Exercises

Isolation Exercises focus primarily on building individual muscles, which helps to build and maintain stability and structure.

It’s common to see people possess the following weaknesses when starting strength training for runners:

- Glutes – Particularly glute medius which helps control hip stability (as mentioned earlier, weakness here is a common cause of patellofemoral pain (17)).

- Hip Flexors – Hence why they’re often so tight.

- Quadriceps.

When significant muscle imbalances occur, we can’t simply load up heavy weight and get them moving.

Due to a process known as neurological inhibition (discussed in | The Ultimate Guide to Strength Training for Beginners | here), they won’t always be recruited and therefore made stronger.

So instead, we have to attack them with higher rep ranges to build up the activation and durability first.

And this, is where the muscular endurance takes place.

Isolation exercises will help address each of these areas in turn – don’t skip over isolation exercises in strength training for runners, they can be just as helpful as the bigger compound movements. The key is making sure you isolate the muscles effectively – you can learn more about how to do that here.

Example Lower Body Strength Session

EXERCISE | Sets | Reps | Load |

|---|---|---|---|

Goblet Squat | 3 | 6 | RPE - 8/10 |

2 | 5 | 75-80% 1RM | |

Suitcase Walks | 4 | 30 seconds each side | - |

Walking Lunges | 3 | 6 each side | RPE - 7/10 |

Weighted Calf Raises (Single Leg) | 3 | 15 each side | - |

Eccentric Focused Reverse Nordics | 3 | 8 | Bodyweight |

Clamshells | 3 | 15 each side | Bodyweight |

Summary

- Running is fairly popular…and for good reason – The barrier of entry to running is non-existent and as a result it’s the go-to exercise choice for most of the general population.

- In the process of evolution, Mother Nature granted animals several impressive physical traits – The speed of the cheetah, the power of the lion, the sight of a hawk…but few people mention, the endurance of man.

- There are a few problems with the traditional approach of “whack on some shoes and go” running training: too much specificity, lack of individuality, improper progression and no attention to weaknesses.

- Running economy and preventing injuries are just two of the major reasons why strength training for runners is essential.

- Strength training for runners should supplement their current training program and be centred around the 8 key movements of strength in order to develop maximal strength.

- This should then be followed by isolation exercises that address muscle imbalances and improve muscular endurance.

References

- Anderson, T. (1996). Biomechanics and running economy. Sports medicine, 22(2), 76-89

- Boling, M. C., Padua, D. A., Marshall, S. W., Guskiewicz, K., Pyne, S., & Beutler, A. (2009). A prospective investigation of biomechanical risk factors for patellofemoral pain syndrome: the Joint Undertaking to Monitor and Prevent ACL Injury (JUMP-ACL) cohort. The American journal of sports medicine, 37(11), 2108-2116

- Bulbulian, R., Wilcox, A. R., & Darabos, B. L. (1986). Anaerobic contribution to distance running performance of trained cross-country athletes. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 18(1), 107.

- Clark, B. C., & Manini, T. M. (2010). Functional consequences of sarcopenia and dynapenia in the elderly. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care, 13(3), 271.

- Conley, D. L., & Krahenbuhl, G. S. (1980). Running economy and distance running performance of highly trained athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 12(5), 357-60.

- Daniels, J. T. (1985). A physiologist’s view of running economy. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 17(3), 332-338

- de Marche Baldon, R., Nakagawa, T. H., Muniz, T. B., Amorim, C. F., Maciel, C. D., & Serrão, F. V. (2009). Eccentric hip muscle function in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. Journal of athletic training, 44(5), 490-496

- Deriex, D., The Effects of Strength Training on Stride Length and Frequency – a comparative study. Technical Bulletin IAAF, 1991, 2, pp.24-27.

- Dousset, E., Steinberg, J. G., Balon, N., & Jammes, Y. (2001). Effects of acute hypoxemia on force and surface EMG during sustained handgrip. Muscle & Nerve: Official Journal of the American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine, 24(3), 364-371

- Faigenbaum, A. D., & Bruno, L. E. (2017). A fundamental approach for treating pediatric dynapenia in kids. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal, 21(4), 18-24

- Garner, S. H., Sutton, J. R., Burse, R. L., McComas, A. J., Cymerman, A., & Houston, C. S. (1990). Operation Everest II: neuromuscular performance under conditions of extreme simulated altitude. Journal of Applied Physiology, 68(3), 1167-1172

- Hickson, R. C., Dvorak, B. A., Gorostiaga, E. M., Kurowski, T. T., & Foster, C. (1988). Potential for strength and endurance training to amplify endurance performance. Journal of applied physiology, 65(5), 2285-2290

- Houmard, J. A., Costill, D. L., Mitchell, J. B., Park, S. H., & Chenier, T. C. (1991). The role of anaerobic ability in middle distance running performance. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 62(1), 40-43

- Johnston, R. E., Quinn, T. J., Kertzer, R., & Vroman, N. B. (1997). Strength training in female distance runners: impact on running economy. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 11(4), 224-229

- Ker, R. F., Bennett, M. B., Bibby, S. R., Kester, R. C., & Alexander, R. M. (1987). The spring in the arch of the human foot. Nature, 325(6100), 147.

- Kyröläinen, H., Belli, A., & Komi, P. V. (2001). Biomechanical factors affecting running economy. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 33(8), 1330-1337.

- Leetun, D. T., Ireland, M. L., Willson, J. D., Ballantyne, B. T., & Davis, I. M. (2004). Core stability measures as risk factors for lower extremity injury in athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(6), 926-934

- Mahieu, N. N., Witvrouw, E., Stevens, V., Van Tiggelen, D., & Roget, P. (2006). Intrinsic risk factors for the development of achilles tendon overuse injury: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine, 34(2), 226-235

- Maldonado, S., Mujika, I., & Padilla, S. (2002). Influence of body mass and height on the energy cost of running in highly trained middle-and long-distance runners. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 23(04), 268-272

- Manini, T. M., & Clark, B. C. (2011). Dynapenia and aging: an update. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67(1), 28-40.

- Marcinik, E. J., Potts, J., Schlabach, G., Will, S., Dawson, P., & Hurley, B. F. (1991). Effects of strength training on lactate threshold and endurance performance. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 23(6), 739-743

- McCarthy, J. P., Agre, J. C., Graf, B. K., Pozniak, M. A., & Vailas, A. C. (1995). Compatibility of Actaptive responses with combining strength and endurance training. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 27(3), 429-436.

- Millet, G. P., Jaouen, B., Borrani, F., & Candau, R. (2002). Effects of concurrent endurance and strength training on running economy and. VO (2) kinetics. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34(8), 1351-1359.

- Mitchell, W. K., Atherton, P. J., Williams, J., Larvin, M., Lund, J. N., & Narici, M. (2012). Sarcopenia, dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength; a quantitative review. Frontiers in physiology, 3, 260

- Saunders, P. U., Pyne, D. B., Telford, R. D., & Hawley, J. A. (2004). Factors affecting running economy in trained distance runners. Sports medicine, 34(7), 465-485.