Regaining strength can be both a daunting task.

Have you lost your gains?

Where do you start?

What should you do to ensure effectiveness and prevent injury?

This is the perfect guide for you.

WHAT?

Learn the topic.

Regaining Strength

Whether you’ve had a forceable time away from heavy lifting due to the 2020 Lockdown, or from another factor such as injury, it’s always useful to have a framework to follow – on how to approach lifting, ensure optimal progression and minimize the risk of any setback.

The key thing we need to keep in mind when regaining strength, is the concept of context:

> What your goals were before time off? And what are your goals now that you’re back in the gym?

> Where was your strength level before?

> What’s your starting point now that you’re back? E.g. if you’re injured, it’s distinctly different from simply having some time off.

Before we go any further, I just want to reiterate the importance of who you are as an individual – if you are an elite athlete, pushing the limits of your performance and potential prior to time off, then chances are you may have detrained a little more than others – but for 99% of the population, the following points apply.

Lose What You’ve Gained…

The concept of hard work isn’t alien to people. And, call me an optimist, but despite how soft we often call ourselves out to be – most people, under the right circumstances can work incredibly hard. Don’t believe me? Go and stand at the finish line of a marathon. Hundreds of people putting themselves through sheer agony – just for the pride of being able to say they’ve done it.

It’s crazy.

No it’s not the fear of hard work – it’s the fear of putting in graft, time and sacrifice – just to have it stripped away from us.

That is what truly messes with our minds.

It’s a fear that everyone in the world of training presents with. You work so hard to gain an extra 5kg on your bench press, to shave a few seconds off your 10km running time, to drop an extra 1% body fat – that the idea of losing all of it – it’s disheartening at best.

And it truly breaks your spirit – interfering with motivation and causing more problems further down the line.

However, fear not – for your efforts were not in vain!

This article will provide some clarity on what you can expect when you first set foot back in the gym.

It will give you hope, and shine a light on what has been a pretty dark time for a lot of people’s health.

Understanding Strength

Now, strength – which as we know forms the foundation for all other attributes – won’t have dropped as much as people think.

When we’re talking about the physiological output of a muscle and how much force it can produce on a neuromuscular level – strength doesn’t fluctuate the same way people make out.

Granted, things like muscle hypertrophy might have reduced slightly – particularly if you neglected your diet and didn’t maintain a regular anabolic stimulus in the form of high protein intake – but that is a separate discussion in itself.

Regaining strength doesn’t have to be fraught with worries about whether or not you have to reclaim everything you’ve lost.

Different Forms of Strength

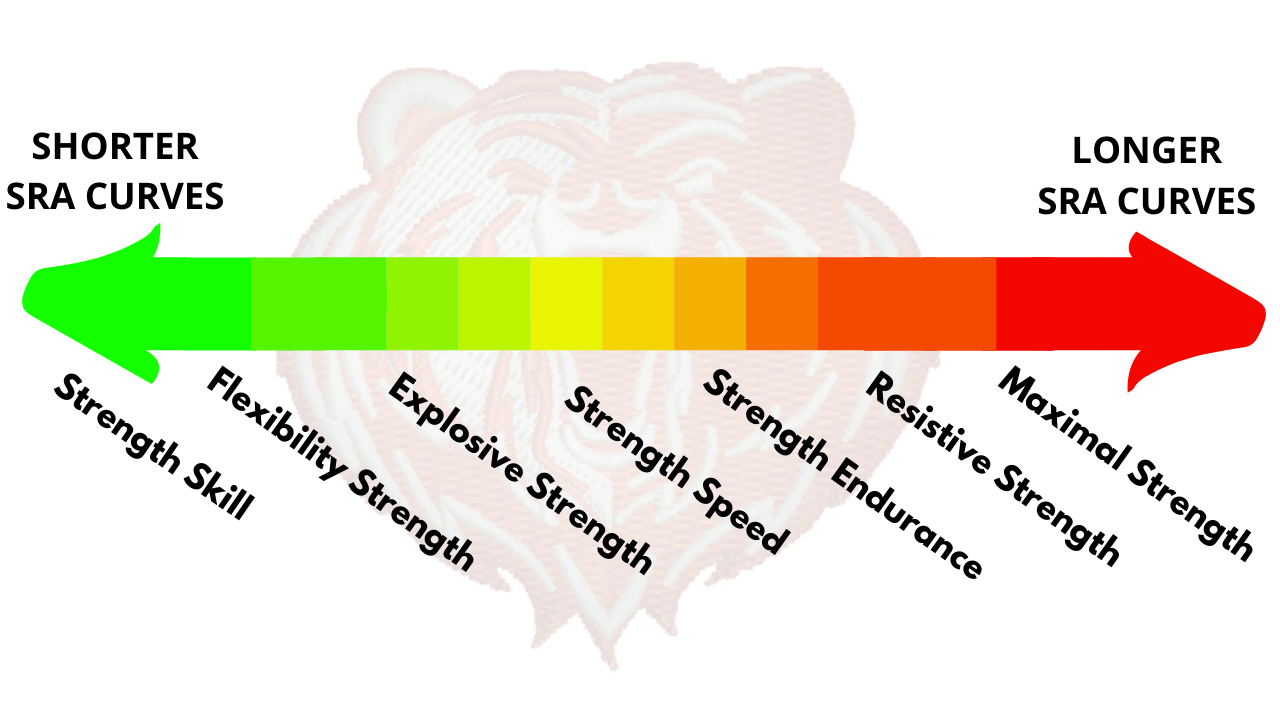

I recently discussed this on an article over at OfficialStrongman.com but not many people are aware that there are several different types of strength – that all works towards a common goal: how much force can you produce and how much weight can you lift?

Now, it’s important to be aware of this – as it has a direct influence over how fast you can hope to not only reclaim what you feel you’ve lost when regaining strength, but also lays the foundation for developing in the future.

Let’s take a brief look at them all in turn:

Type of Strength | Definition | Example Exercise |

|---|---|---|

Maximal Strength | Production of Maximal Force | 1RM Deadlift |

Strength Endurance | Sustain high amounts of force over prolonged period of time | High Rep Bench Press |

Strength Speed | Produce high amounts of force as quickly as possible | Submaximal Back Squat |

Resistive/Reactive Strength | Absorb/resist or control high amounts of force acting on the body | Nordic Hamstring Curls |

Skill Strength | Produce high amounts of force within highly coordinated movement | Clean and Jerk |

Explosive Strength | Produce force rapidly, with a continual acceleration profile (AKA Power) | Snatch |

Flexibility Strength | Produce force over a long range motion | Deficit Stiff Leg Deadlift |

SRA Curves

Now that we’re aware of the different types of strength – we’re already off to a running start when we are regaining strength.

One final point to cover is the notion of Stimulus – Recovery – Adaptation (SRA).

When we train – the stress isn’t just placed on the Muscle. It’s placed on the body as a whole, which typically affects all 4 of the following Systems.

4 BODY SYSTEMS FOR TRAINING

Muscular System

All aspects of Skeletal Muscle, from cross bridge cycling to leverage during movement.

'Fascial' System

Comprised of Bones and other Connective Tissues such as Ligaments, Myofascia etc.

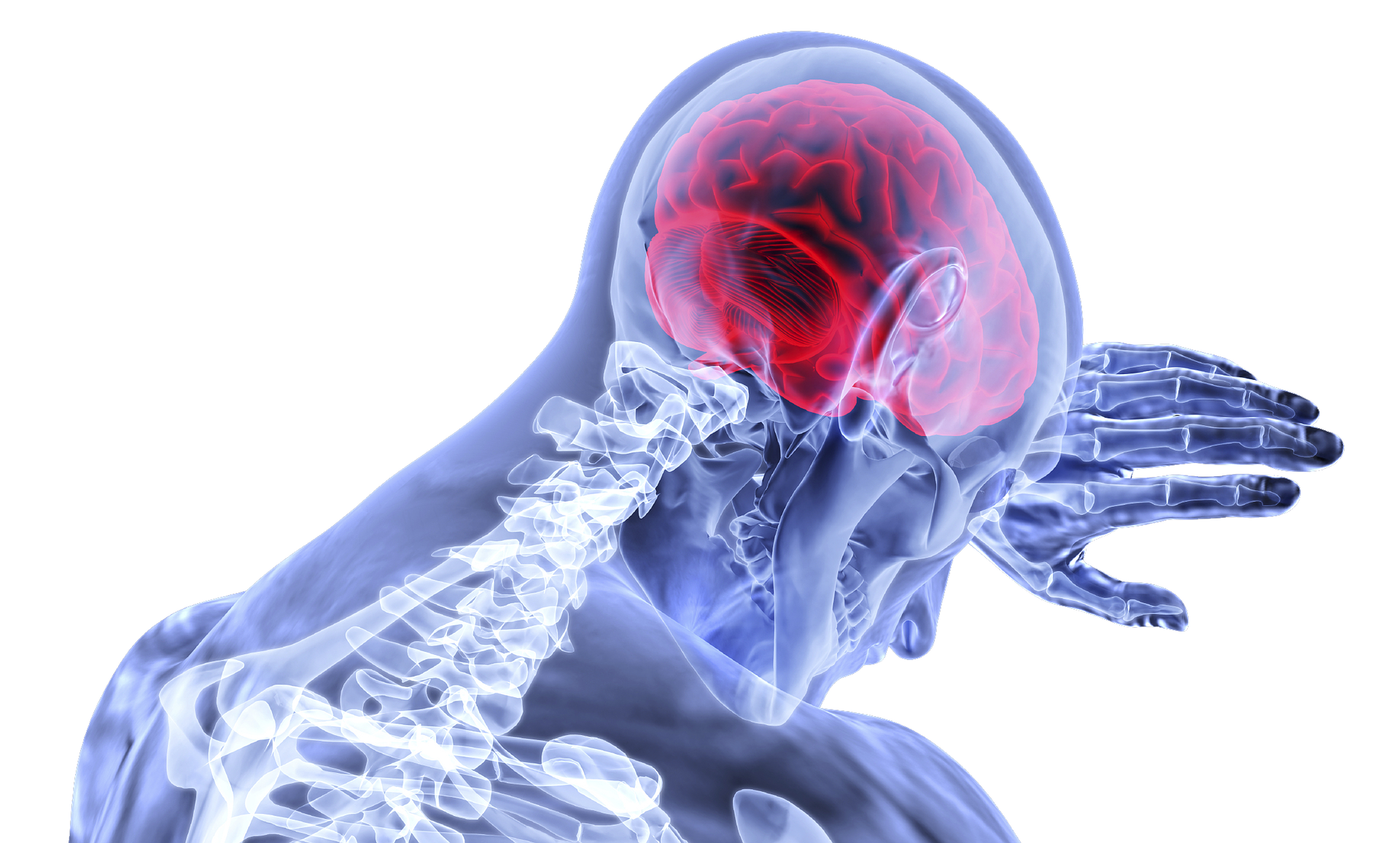

Psychological System

Comprising our perception of stress - taking into account Mental Fatigue, Emotional Response etc.

Neuro-Endocrinological System

Although distinctly different, they fall into a similar category, based off the Sympatho-vagal Response.

To put it simply - Nerves and Hormones.

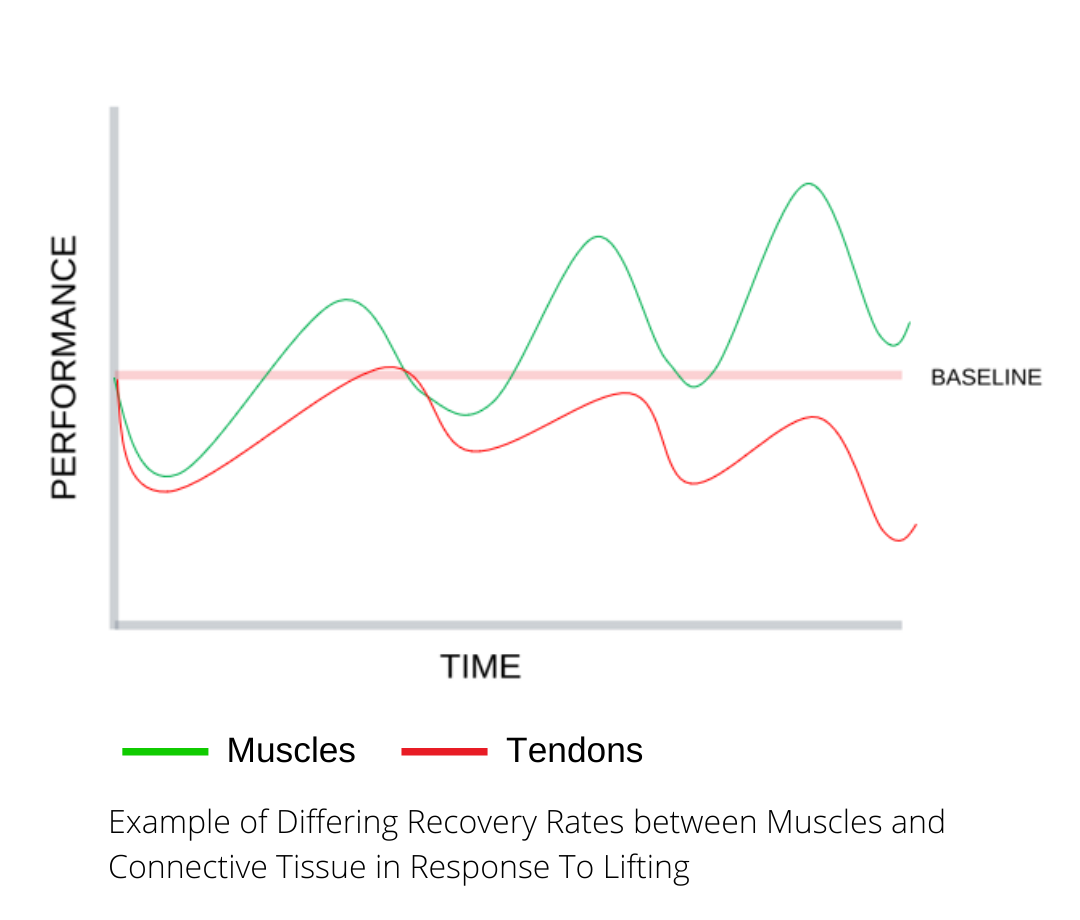

SRA Curves allow us to essentially model and aim to define how each subsystem of the body (muscular, fascial etc.) is influenced by external stress (training).

From this, we can take a few things:

> How Much Fatigue is Required to in order to elicit a training response

> How Fast You Can Expect to Recover from a bout of training.

> How Often you Can Train a Specific Quality.

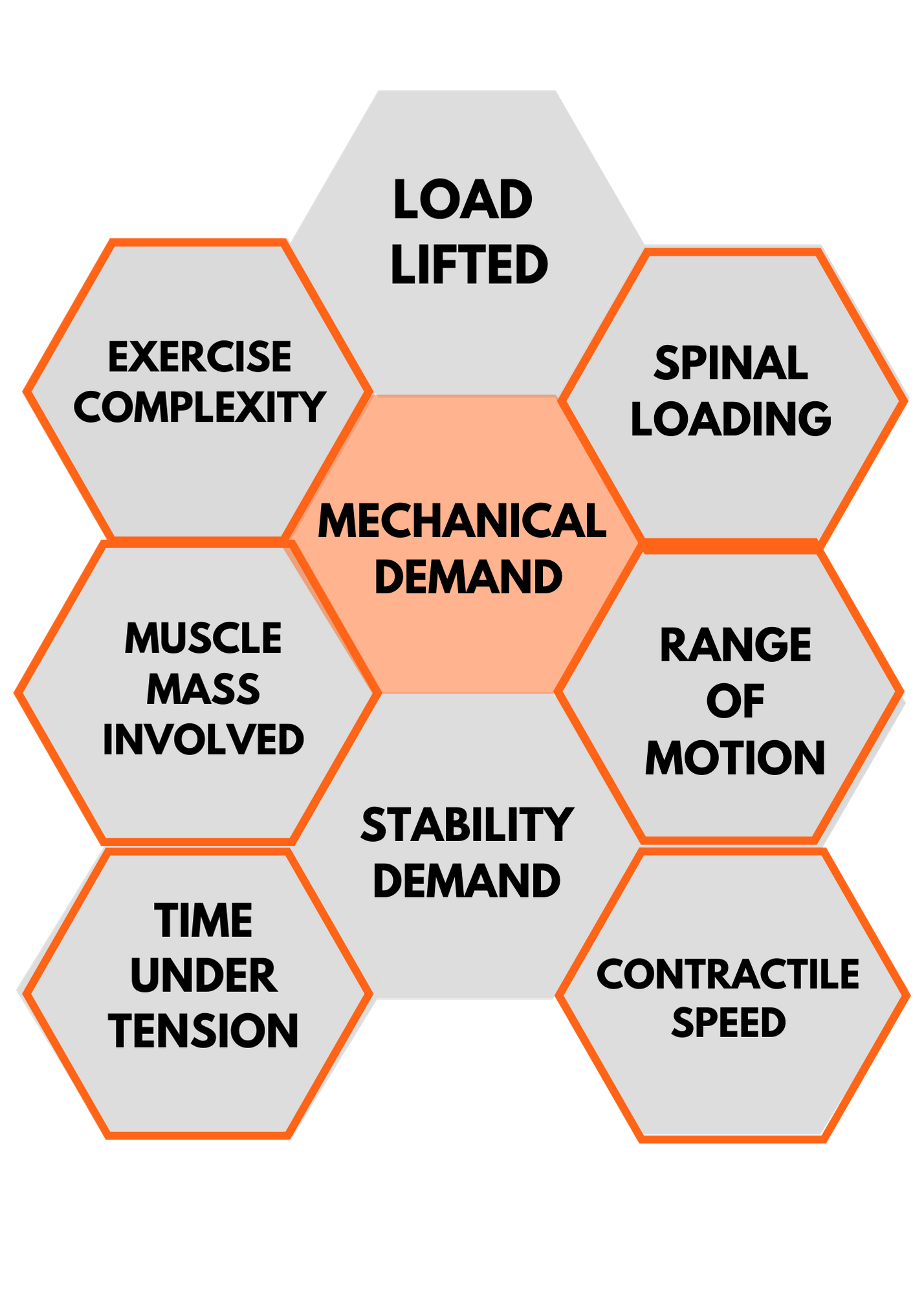

Each bodily system outlined above, has a different SRA curve – they all recover at different rates from the same bout of training – dependent upon a variety of different things known as Mechanical Demand Factors – which is something we’ll touch on in the application section.

EXAMPLE OF DIFFERENT RECOVERY RATES

EXCERPT FROM THE UNSHAKABLE STRENGTH PROTOCOL

The concept of fatigue and how to manage it in response to training is covered in detail, in our latest product - The Unshakable Strength Protocol.

ANOTHER EXAMPLE

A 1RM Deadlift

Very High Stress

Neuro-Endocrinological System

High Stress

Psychological System

Moderate Stress

Fascial System

Low Stress

Muscular System

Harder and Longer…

It’s relatively simple when you look at it in this light.

Ever heard the phrase: You lose it as quick as you gained it?

It’s the same with strength.

The harder the quality is to improve over time. The longer it will take and the more fatigue you will have to go through to be able to improve.

However, the longer it will take to diminish as well.

So when you are regaining strength, we can use this to our advantage: as each strength quality also has a unique SRA Curve.

They exist along a continuum that you can see below:

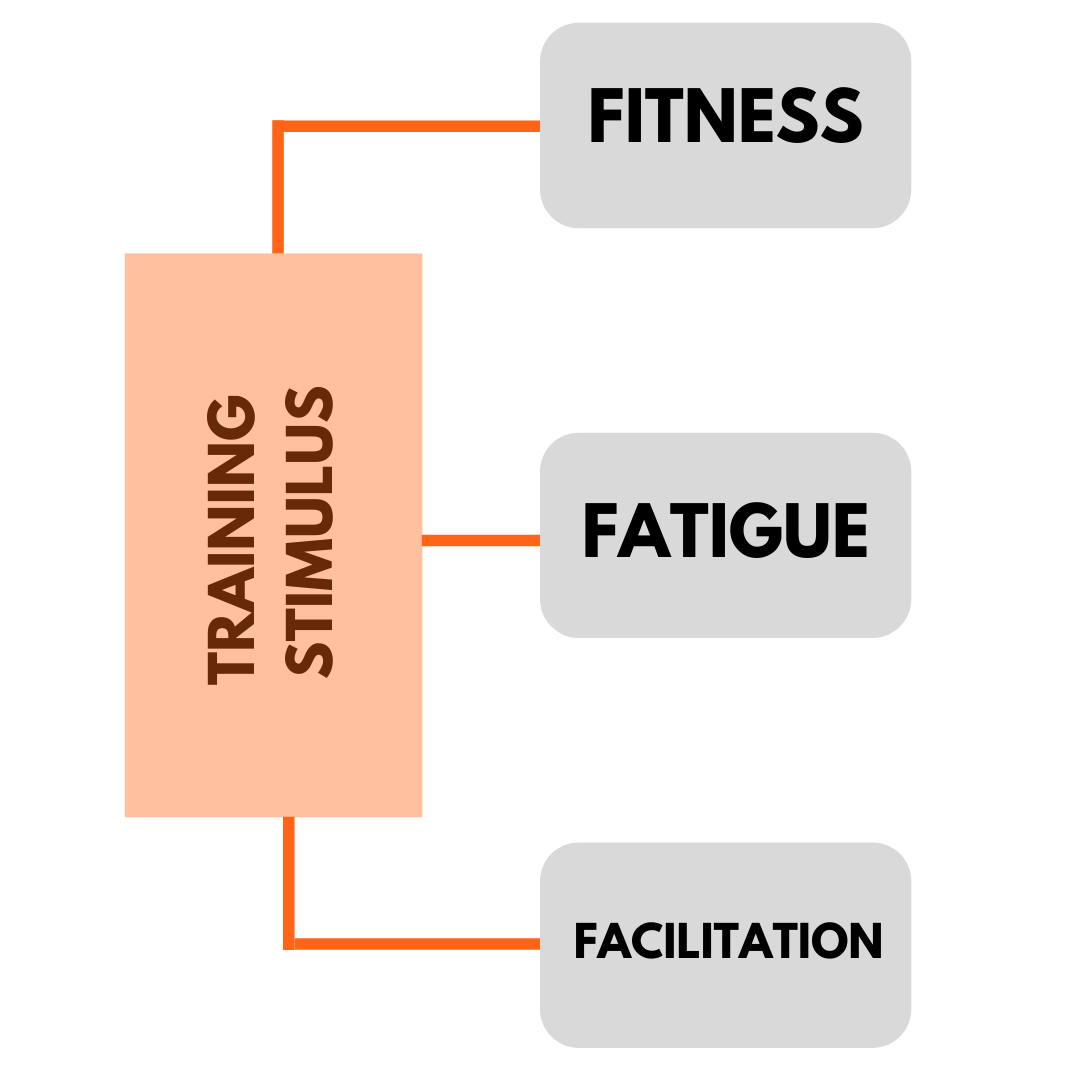

3 Factor Model

One final thing to consider when we discuss training is the 3-factor model, on how we train to improve any fitness variable.

The 3 Factor Model explains how when we train to improve something, there is a resultant bout of fatigue that is experienced, as well as an acute “potentiation” effect.

This is important, as it’s not as simple as “spending more time” working on one component.

There is a point of diminishing returns within each training phase, training session – even each specific exercise, based off the magnitude and sequencing of the stimulus.

Heuristic displaying the 3F Model for Training Response.

Let’s use an incredibly simple example.

We want directly work on improving maximal strength. Which would require lifting maximal loads, let’s say 95% 1RM.

Now, at first glance, you would think that continuing to hit heavy singles at 95% would build maximal strength in a linear format.

If you could do 20 reps at 95%, surely that’s better than doing 5 reps, right?

Well, no.

2 Reasons:

- If you could hit 95% for more than 10 reps in a given session – it’s not 95% of your true max, is it?

- The fatigue that is accumulated as a result of overworking the specific fitness component simply isn’t worth it.

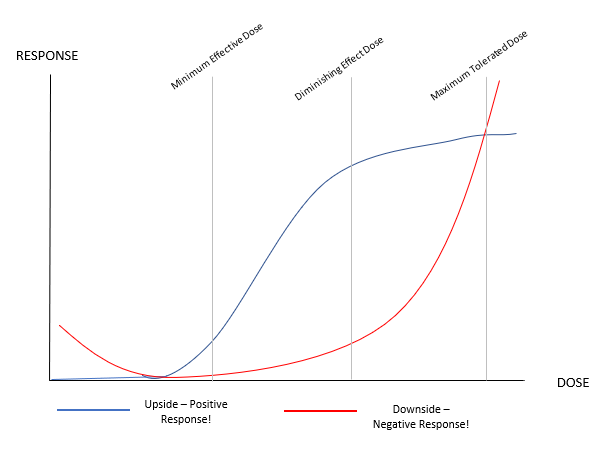

It’s all about finding the sweet spot between the Minimum Effective Dose (the smallest amount of training you need to do to make gains) and the Diminishing Effect Dose (the point at which the downside e.g. potential injury risk – outweighs the benefits).

Example Graph (Adapted from Agile Periodization by Mladen Jovanović)

The final part of the puzzle is the idea of Facilitation, or in the research, more commonly referred to as Potentiation; which is an acute increase in performance (before the fatigue sets in).

Although it has a small role to play, it can still be leveraged to seek out extra gains within a training session.

Again, keep the heavy work in mind.

Let’s say we’re working with 90% Back Squat. Although we will have hit a point of diminishing returns in the “Maximal Strength” section – doing this heavier work opens up the ability to improve other types of Strength.

Performing a set of heavy Squats, with high levels of Exertion – stimulates the neuromuscular system, priming your body and recruiting a higher number of motor units for explosive Contractions – allowing you to potentially run further, jump higher etc. (2).

HOW?

Learn the implementation.

So, now we have the key concepts laid out, let’s dig into the nitty gritty of how to maximise the time when you are regaining strength.

How do we structure our training?

Which Have you Lost?

Whenever you’ve had a significant amount of time away from the gym, each of the strength variables are lost at their own commensurate rate, based on the SRA curve length and where we were prior to your time away from the gym.

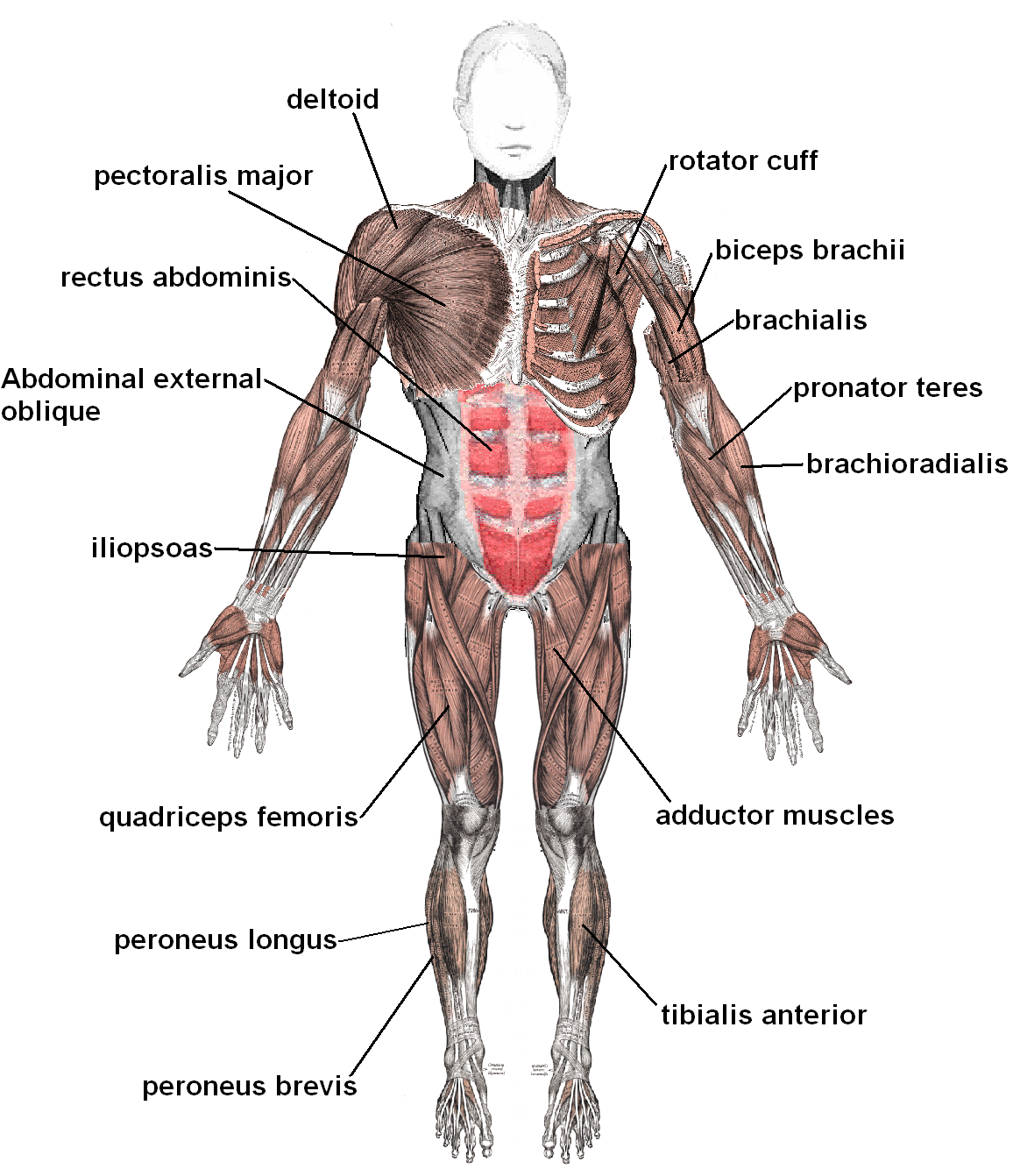

As we said at the start of the article, the actual, physiological output of the muscle won’t have changed as much as people may have thought. But when regaining strength, the two main variables that will have been lost for most people are:

Skill Strength

&

Explosive Strength

Listen to Advice

“Don’t lift heavy…”

“Take your time…”

“Be careful…”

They are all valuable bits of advice being touted across social media – but let’s face it.

How many people are going to listen?

This is coming from someone who is a scientist first, meathead second – but even I can’t wait to get back to serious training.

The key is, using the principles above and a few clever tricks to get you feeling like you’re working as hard as you want – in a slightly different way.

Deconditioned Tissues…

It’s all well and good to talk about what the body is capable of – but what is it capable of tolerating?

Typically, a lot of overuse injuries involve overworking connective tissue that simply don’t have the same blood supply as skeletal muscle.

When you have a significant layout from training, tendons can lose their stiffness and we can see alterations in the collagen structure meaning they might not tolerate the same loads the muscle can lift (4).

To compound the potential problem, the reduced skill strength means people will often lift in a slightly different way to usual – creating a different pressure gradient between the weight that’s lifted AND the stress the connective tissues experience.

Fortunately, we can actually use these issues and the principles above to create a safe and effective method of training when we are regaining strength.

Specific Training Methods

1. Increase Training Frequency

In the world of Periodization, it’s not just about the total work you do, but also the division of that work across each session.

This can be broken into Extensive and Intensive Models.

Intensive Training is when training that focuses on one factor, movement, muscle etc. Takes place over a relatively short time. As a result, the fitness is developed quicker, but the fatigue is greater (as we’ve discussed, from the 3 Factor model).

And then Extensive Training, where we can divide the training dose over a longer period of TIME – this is the approach we’ll be taking when regaining strength.

Instead of having the typical Push Pull Legs Training Routine that a lot of people follow…

…You should start by dividing your training across multiple sessions, adopting closer to a full-body approach.

This will mitigate the likelihood of breaching your maximal recoverable volume and you will also be able to improve your skill strength to a greater degree.

This is a well-known area of study within behavioural psychology – we learn skills much faster when we employ fragmented practice with regular intervals (allowing the brain to create, reinforce and solidify new motor skills.

2. ECCENTRICS and ISOMETRICS

Although we didn’t discuss it in depth, another key variable that is lost at a much faster rate than maximal strength is “Resistive” strength – the ability to control loads/centre of mass.

Placing an emphasis on the eccentric contraction phase of a movement, brings a whole host of benefits that most people simply don’t gain from dynamic training.

ECCENTRICS

Our in-depth discussion on Maximizing Eccentrics.

ISOMETRICS

Our complete guide on Isometric Training.

What Benefits Are There?

For eccentrics – One of the biggest advantages we find when emphasising the Eccentric phase of the movement – is the improved proprioception. For whatever evolutionary reason, there is a heightened degree of biofeedback during the lowering phase of each movement (5, 6).

In addition to that…

ISOMETRIC TRAINING, in my opinion, is one of the greatest, and yet most underutilised method of getting strong there is.

We won’t cover Isometric Training in too much detail – but to keep the scope of this article in mind, isometrics give us two major benefits for when we structure our training and we’re regaining strength:

1. Increased Tendon/Connective Tissue Stiffness

This is arguably one of the greatest benefits of Isometric Training – reorganising the collagen matrix, reducing the likelihood of sustaining overuse injuries and building stronger tendons will be a catalyst for regaining your strength and beyond.

2. Improve Stability

In the same way eccentric training provide benefits for stability during movement, isometrics help to improve static strength endurance, strengthen and improve the ability to maintain a strong, structural position and the ability to maintain a solid.

Although there are Supramaximal methods for both eccentric and isometric training that can increase maximal strength, for those regaining strength, we strongly recommend simply increasing time under tension during the Eccentric phase and implementing Positional Isometrics (e.g. Pause Squat).

Implementing eccentric isometrics will not only improve the rate at which we regain our skill strength, but it will also limit the load that we can lift or, another way of looking at it – Increase the Exertion level at the same weight – keeping you safe in the long run!

UNSHAKABLE STRENGTH PROTOCOL

Get your hands on The Unshakable Strength Protocol - maximize your strength potential.

Figure 1: Heuristic showing Mechanical Demand Factors - variables that can be adjusted to increase exercise intensity and increase strength.

3. Decrease/Progress – Mechanical Demand Factors

I have written about this extensively before – but there are other forms of progressing exercise intensity, outside the realm of simply adding weight.

And if you’ve continued to train during your time away from the gym, you’ll be aware of at least some of them.

Ironically, one of the easiest ways to improve strength, health and performance in a vast majority of the population – is to spend at least a small portion of training time – working on another area outside the realm of just: more weight.

4. Conditioning and Core

Going back to the realm of SRA curves for a second and looking into other fitness components outside “strength”. We find that each fitness component has a different length curve.

With aerobic efficiency being one of the easiest components to improve and quickest to deteriorate.

In other words, you’re not necessarily weaker, but you’re more than likely – much less durable. So spending a dedicated amount of time on improving your energy system efficiency and training in a way that improves your “fitness” will help set you up in the long run for future progression, after regaining strength.

To add to that, one of the key areas that can never be worked too often – core strength and the ability to Brace when LIFTING, is an essential part of being strong and is integral to maximizing strength (1).

Again, this is a valuable method in which you can increase training Exertion without taxing your recovery as much as max effort deadlifts.

GUIDE TO CORE TRAINING

Complete Guide to Maximizing the effectiveness of core training.

GUIDE TO CONDITIONING

Conditioning is an integral part of the strength training journey.

Psychology of Training

There is one final thing to note before we go through a real-world example and provide you with the tools to maximise your training when regaining strength.

Motivation, dedication etc. Whatever you want to call it – is influenced directly by our own inner narrative.

The narrative is essentially the inner dialogue and the story we tell ourselves about the state of a particular facet of our life.

The Peak End Theory states that our narrative is formed by the sum of the Peak Moment in recent memory and the most recent memory you have (3).

NOT the sum of the total situation.

So, it helps to END each training session on a positive light. Provided it doesn’t contradict or interfere with any of the points above. It’s not a max effort deadlift – I would actively encourage you to end each training session with 10 – 15 minutes of a body part, exercise etc. That you really enjoy. For no particular reason, other than you enjoy it!

Example Program

Lets take a typical split that many people follow – the infamous…

Using the leg session as an example, let’s say your typical leg strength training session looked something like the following:

EXERCISE | SETS | REPS | INTENSITY | M.DEMAND FACTOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Low Bar Back Squat | 3 | 3 | Load Lifted + Spinal Loading | |

Leg Press | 3 | 8 | Load Lifted | |

Hack Squat | 2 | 12 | RPE 9 | Load Lifted Range of Motion Time Under Tension |

RDLs | 2 | 6 | 60% Deadlift 1RM | Load Lifted Spinal Loading |

Barbell Calf Raises | 3 | 12 | RPE 10 | Load Lifted Time Under Tension Contractile Speed |

Utilising all the theory we have just learned, we would want to adjust the session – so it would look something like this instead:

EXERCISE | SETS x REPS | INTENSITY | M.DEMAND FACTOR | EXECUTION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

3 x 3 | RPE 9 | Load Lifted Time Under Tension Contractile Speed | 3 Pauses during Eccentric Phase | |

3 x 5 | RPE 8 | Spinal Loading Complexity | 3 sec Isometric Hold in Bottom Position | |

2 x 12 | RPE 10 | Stability | Emphasize full range of motion. Maintain constant tension. | |

2 x 6 | 15 - 25% DL 1RM | Stability Complexity | Emphasize full range of motion - pausing in stretched position | |

3 x 12 | RPE 10 | Time Under Tension Load Lifted | Hold peak contraction for 2 seconds, lower for 2. Maintain constant tension. |

We would then take these exercises and split them across two training sessions, balancing them with upper body work in order to, as we said, increase training frequency and capitalise on Skill Strength gains in the short term.

Reference List

- Barbosa, A. C., Martins, F. M., Silva, A. F., Coelho, A. C., Intelangelo, L., & Vieira, E. R. (2017). Activity of Lower Limb Muscles During Squat With and Without Abdominal Drawing-in and Pilates Breathing. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(11), 3018-3023.

- Esformes, J. I., & Bampouras, T. M. (2013). Effect of back squat depth on lower-body postactivation potentiation. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 27(11), 2997-3000

- Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B. L., Schreiber, C. A., & Redelmeier, D. A. (1993). When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science, 4(6), 401-405.

- Magnusson, S. P., Hansen, P., & Kjaer, M. (2003). Tendon properties in relation to muscular activity and physical training. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 13(4), 211-223

- Matthews, P. B. (1991). The human stretch reflex and the motor cortex. Trends in neurosciences, 14(3), 87-91

- Yue, G. H., Liu, J. Z., Siemionow, V., Ranganathan, V. K., Ng, T. C., & Sahgal, V. (2000). Brain activation during human finger extension and flexion movements. Brain Research, 856(1-2), 291-300