Core Strength training often eludes most gym goers. Whether it’s sticking to the same routine of crunches and side bends or simply neglecting it altogether – everyone could do with the answers to correct core strength training.

And here it is.

Back Pain and Poor Posture in every day movement. Knee pain during the squat. Lack of stability in exercise or poor balance in certain movements. Each of these problems plague most day people day to day. But can all be rooted back to one potential cause:

Core Strength training and Stability.

Set the Scene

Gareth had always wanted to improve his core strength. He tried all the popular programs, working from the more gimmicky “6 minute abs” right through to trying his hand at writing his own routine. But non seemed to work for him. He had been told from one person that situps were the way to go from another saying that planks were the forward and then another person saying heavy squats and deadlifts were the key to a super strong core.

Which was he to believe?

Although most often dream for the “flat stomach” or “ripped abs”, core strength training has a much greater influence on the human body than simply the way it looks. And because it’s something that most people desire (you’d probably be lying if you said that a part of you didn’t want your abs to show), there’s an abundance of misinformation swimming around the fitness community, on how to effectively build core strength.

WHAT?

Learn the topic.

What is the Core?

The core can be comprised of several component parts and is often disputed amongst fitness professionals as to how much of the body can be considered as an element of “core musculature”. Although the core is essential for a wide array of bodily functions, we are only really concerned (in the scope of this article) with how the core effects lumbo-pelvic stability and spinal position, intrabdominal pressure (IAP) and overall postural integrity.

Core strength training has previously been defined as…

…the ability of the lumbopelvic-hip complex to prevent buckling of the vertebral column and return it to equilibrium following movement (12).

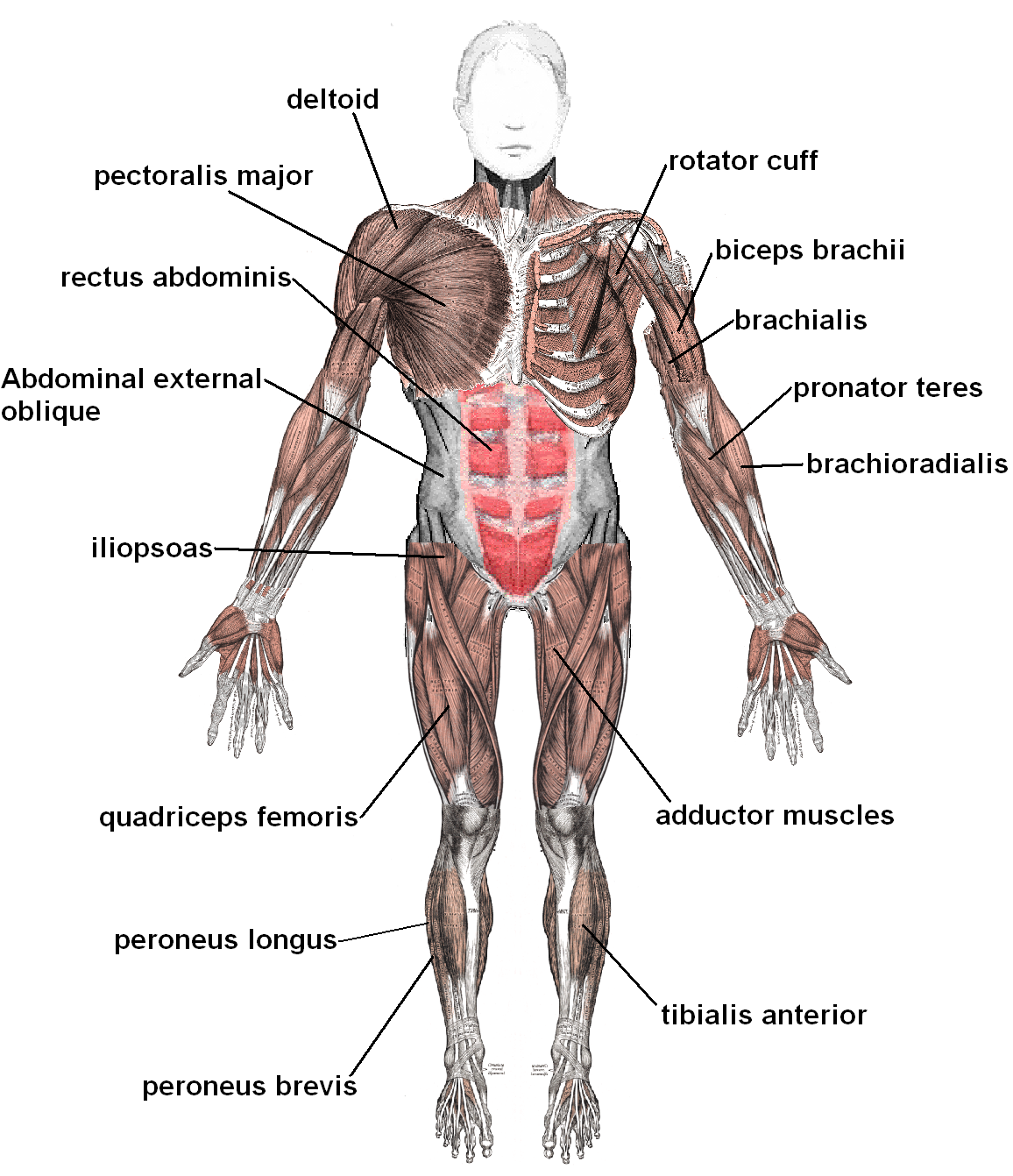

So, when talking about the core as an isolated region of the body, we’re talking about the following 2 regions:

Antero-Lateral Wall of the Abdomen

The anterior compartment of the core involves a muscle known as the rectus abdominis. The main muscle of the “six pack” region that is primarily responsible for postural maintenance –

- When fixing the pelvis in place; contraction results in flexion of the lumbar spine/lower back.

- When fixing the rib cage in place; contraction results in posterior pelvic tilt (7).

Weakness of this muscle can result in one of two issues:

- High tone of the neck musculature during core strength training exercises (due to an inability to fix the rib cage in position).

- Hyper-lordotic (bum out) posture (10).

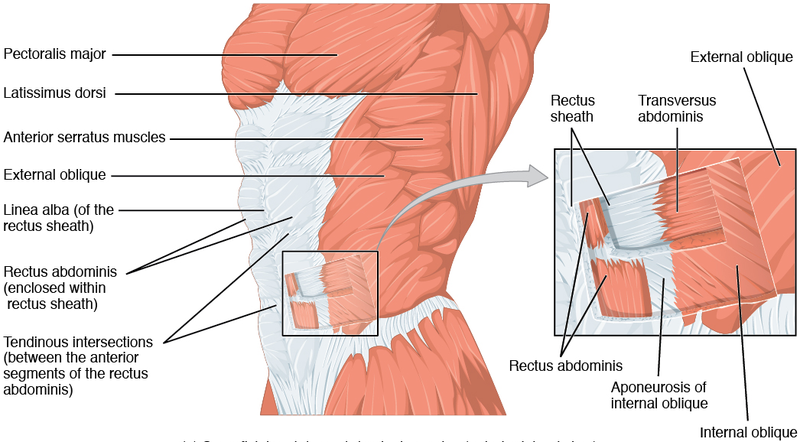

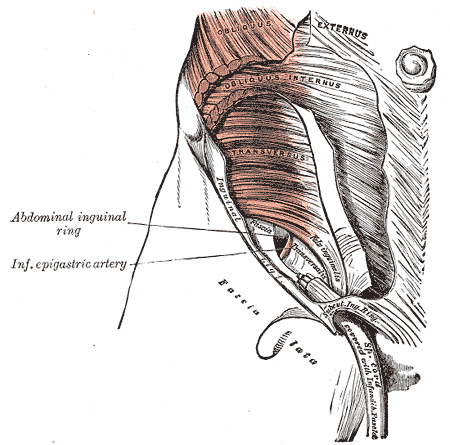

Lateral Abdominal Wall

Although the anterior wall is still essential, the next layer is far more important when it comes to core strength training. The lateral abdominal wall is comprised of 3 major muscles:

External Obliques

Acting together on both sides of the body = Spinal flexion (pulling the body over)

Acting one sided: flexion towards the side they are contracting on (i.e. the left oblique flexes the trunk to the left) and rotation of the trunk to the opposite direction (7).

Internal Obliques

Acting one sided: flexion and rotation of the trunk towards the side they are contracting on (7).

Essential for generating IAP and supporting the abdominal wall.

Transverse Abdominis (TrA)

Primary function to draw the abdominal wall inwards and to…

…Stabilise the lumbar spine and pelvis, prior to movement of the lower or upper limbs (11).

Common Considerations

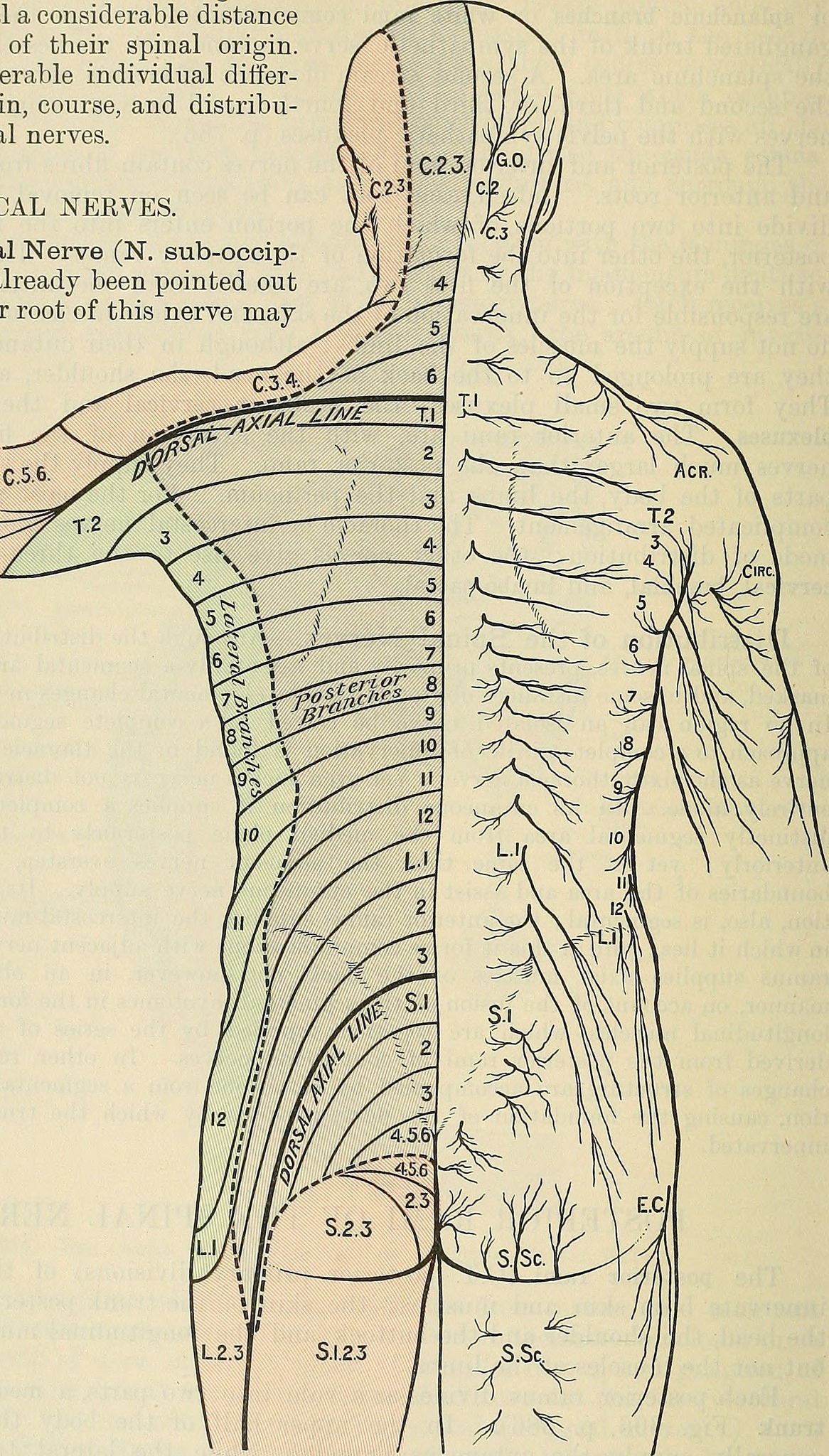

Nerve Innervation and Thoracic Spine Mobility

This is a little gem I learned when investigating core anatomy, that most aren’t aware of and may directly influence your core stabilisation.

All of the above muscles are innervated primarily from the lower six thoracic nerves (2). And, when thoracic mobility is restricted, compression of the tissues in this area may result in reduced activation of the muscles they innervate.

In other words, in the interest of balancing out strength throughout the body, you may need a mobile thoracic spine and complete overhead mobility to optimise your abdominal activation.

Relation to Thoraco-lumbar Fascia

If you weren’t aware alrwady, there is a huge sheath of tissue across the back, which connects the shoulders to the hip known as the Thoraco-lumbar fascia. It relays signals between muscles such as the glutes and latissimus dorsi to increase strength in a wide array of exercises.

The transverse abdominis and internal oblique muscles are connected to the deep layer of the thoracolumbar fascia (4, 5, 14).

This means that as well as stabilising the spine, these 2 core muscles will directly contribute to transferring the force generated from the legs/hips up to the shoulders and may have the greatest involvement during heavy loaded movements like the squat and deadlift.

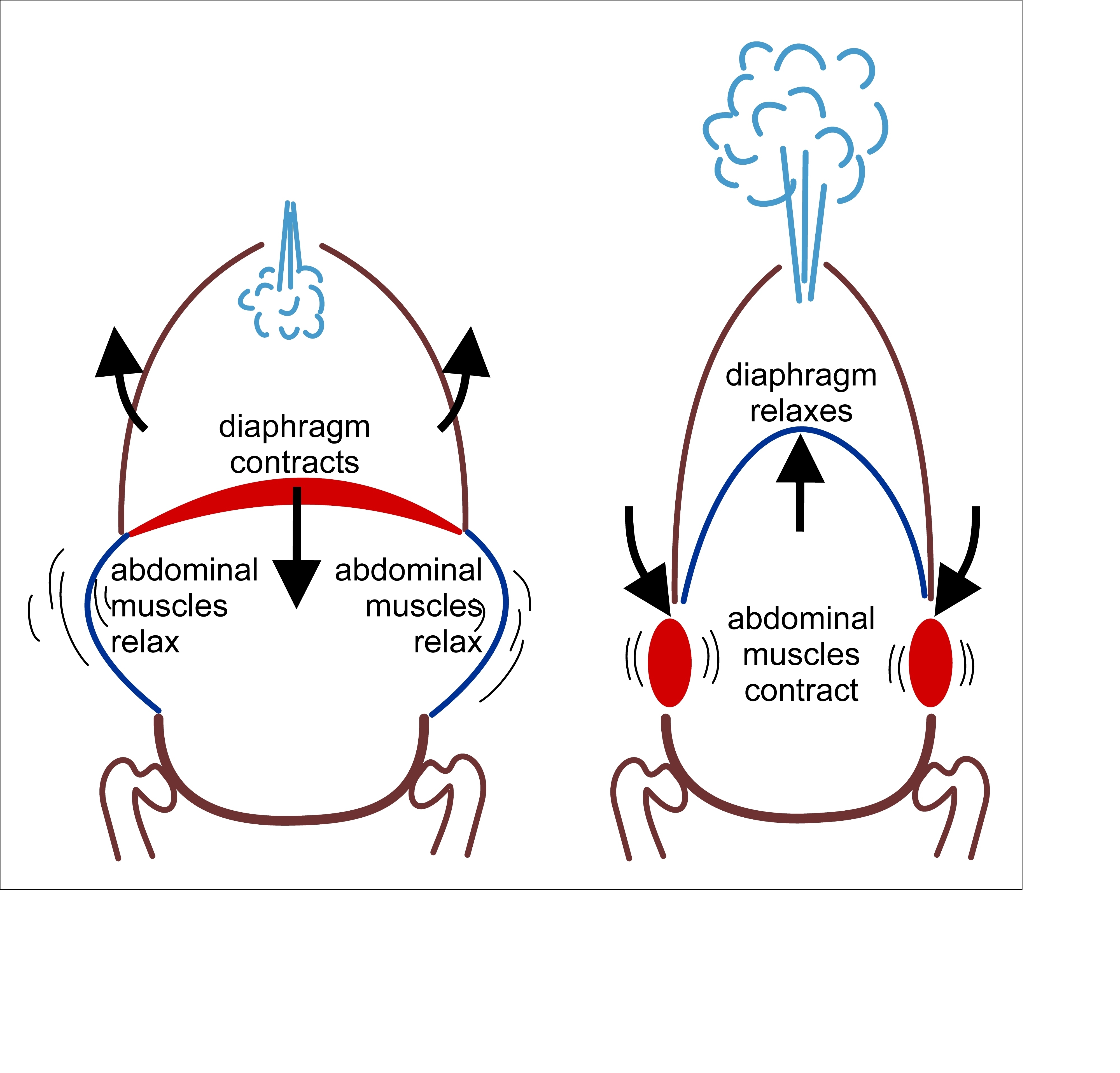

Intra-abdominal Pressure (IAP).

Although this is an entirely separate field in of itself, the importance of IAP can’t be overstated.

There’s so much research available showing how IAP positively influences spinal stability I won’t even quote the papers. Just know that if you’re not doing it already…

…you need to learn. Fast.

Fortunately, I’ve covered the 1st major part of generating IAP, which comes from diaphragmatic breathing. The second part after breathing, is that you’ve gotta brace, which comes from the connection to, and strength of, your core musculature.

WHY?

Learn the science and theory.

Control yourself proximally, before you control things distally – Eric Cressey

This basically means, control the core, before you try and control your arms and legs.

Many coaches, physical therapists and health related professionals rightly believe the core to be the root of everything and have a large degree of influence on all forms of health related impairment. Whether this comes in the form of poor movement, nagging pain or even immune system health, the ability to effectively control core musculature is essential.

Below included the top 5 reasons the core is an area of the body that should be trained on a regular basis

1. Over Extended and Over Flexed – Postural Maintenance

We all know that sitting down for prolonged periods of time is bad for us. But, suffice it to say, standing up for an equally long period of time can be just as bad on your posture over the long term.

“So, what then?! I can’t sit. And I can’t stand. What is the body good for?”

Movement.

As I’ve mentioned before, your best position is your next position. But I’m fully aware that we can’t spend all day walking around the office, telling your boss that you’re still able to get your accounting work done whilst jogging on the spot on performing lunges with a cup of coffee in your hand and a spreadsheet in the other.

So, if you can’t do that (sucks to be working at your place), then instead you should be addressing these issues in training. If, of course, you care about your health long term.

It just so happens that the ability to establish a good posture and combat the effects of over-extended standing or over—flexed sitting comes in the form of appropriately training your core (namely your rectus abdominis in this instance)

2. Spinal Stability

Core strength training is essential for spinal stability. There’s not much else to say besides a stable spine during dynamic movement (or under any position of load) simply cannot be stable if the core musculature surrounding it is weak (9).

3. Injury Reduction

There is an ever-growing body of literature linking core strength training to injury rates in more or less every joint of the body from the lumbar spine (3) to other more distal areas of the body such as the shoulder (13) and knee joints (1).

Common Injuries such as…

ACL. An injury all too common in sport in the form of non-contact ACL injuries are also linked to core strength and stability, due to an individual’s ability to control torso position and therefore loading throughout the lower body.

Groin Strains. Ever had a groin strain? The rectus abdominis attaches to the same aponeurosis (layer of connective tissue) that one of the key groin muscles (Adductor longus) also attaches to. Therefore, core strength training also plays a huge role in preventing groin ruptures (8).

4. Expiration/Respiration – Cardiovascular Fitness

When we have a healthy breathing pattern, chances are there’s nothing to worry about.

However, as we’ve discussed before, most of us don’t breathe properly, meaning our cardiovascular fitness will be negatively effected.

When breathing at rest, exhalation (breathing out) is largely a passive action. Meaning we don’t have to use any energy to breathe out. However, when ever we have to generate forceful exhalation (i.e. during intense cardiovascular exercise to get rid of CO2), the core muscles are essential for this process.

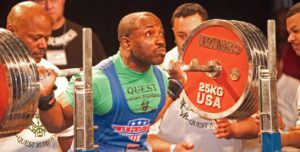

5. Transferring Force

And finally, the one we’re wanting to hear about, is the direct effect the core has on overall strength.

You should literally see the core as the buffer through which force transfers from the legs up into the torso and shoulder joint.

The squat, deadlift, bench press, military press, rows, pullups, pressups etc. Everything that involves the hip and shoulder joint will…in one way or another…involve the core.

We know that the core attaches directly to the thoraco-lumbar fascia, which is the connection between the shoulder and hip joints.

Adding to that, you should be aware by now that the ability to correctly position your joints (particularly your lumbar spine and pelvis) has a huge bearing on your body’s excitation pattern.

If there is something dodgy going on down there, you body won’t be having any of it…and down-regulate force output in it’s extremities to protect you.

Again…

Control yourself proximally, before you control things distally – Eric Cressey.

HOW?

Learn the implementation.

If we refer to the functions above, we can see that each region of the core is biased towards performing individual movements (e.g. oblique creates rotation).

However, which muscle action do we want?

Although we can target the muscles with a focus on either concentric, eccentric or isometric muscle actions; it would be much more effective to not only provide a variety but to also bias them towards what you are aiming to achieve and, where your starting point is.

Muscles are roughly 20-40% stronger when lowering a weight than they are lifting. They are much stronger isometrically and then at their weakest when being asked to lift something.

Although you are at your strongest with eccentric muscle actions, dynamic movement is also much harder to control.

If you are unable to effectively stabilise your spine using your core, then whenever possible, you should start out using isometric exercise first, followed by eccentric and then finally concentric muscle actions.

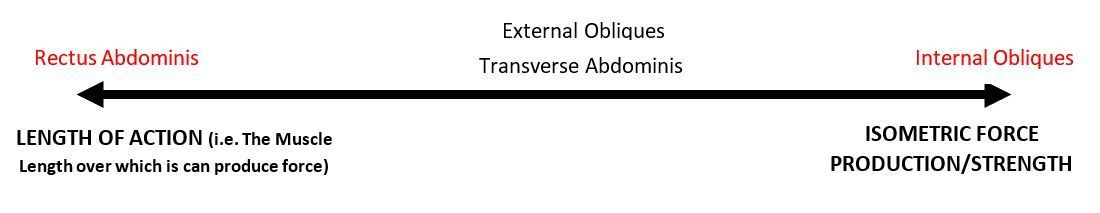

To add to that, research investigating the architectural structure of each abdominal muscle shows that each of the four component parts, possesses different levels of strength and a completely different “length-tension relationship”, or in other words, “how strong it can be at different ranges of motion” (6).

In a nutshell, the study found the following:

Adapted from findings of Brown et al. (6)

Can you Isolate It?

Although you can never truly isolate a muscle to work on it’s own, the core is even harder.

We can’t only train the rectus abdominis, but we can bias an exercise towards it’s functions and what range of motion it prefers to work within.

1. Rectus Abdominis

“Train the rectus abdominis to control the movement into and/or to resist spinal hyper-extension, ideally over at a long range of motion”.

Another way to word this, is to train the rectus abdominis to maintain a neutral posture and challenge this by simply taking the two support points further away from one another and taking the muscles to the most stretched position possible.

Example Exercises

Extended Plank – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_N0ZGN3sBg

Barbell/Ab Wheel Rollout – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5I3LgiumTJM

2. External Obliques

The external obliques are naturally stronger than the rectus abdominis and sit as the “middle ground muscle” able to produce “decent” force over a “decent” length (as seen above).

It can be trained through flexion and/or rotation (or resisting both of these functions).

Example Exercise

Weighted Carries (Anteriorly Loaded – Picture shown)

Landmine Twists – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDakeCOBdDE

3. Internal Obliques*

Although they primarily resist trunk rotation, they also have a key function in the stabilising the abdominal wall under pressure and are directly attached to the thoraco-lumbar fascia*.

As a result, the internal obliques can be trained to support the spinal column/pelvis position, whilst exerting IAP and to resist lateral flexion or twisting.

Example Exercise

Side Plank w/Leg Lift (Picture Shown)

Laterally Offset Carries (e.g. Suitcase Walks) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ye1GFuAj4hc

4. Transverse Abdominis (TrA)*

This muscle is also connected directly to the thoraco-lumbar fascia, stabilises the lumbo-pelvic region during limb movement and draws the stomach inwards.

Example Exercise

Dead Bug (Picture shown)

Stomach Vacuum – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDx1xfSobG4

*The internal obliques and TrA directly attach to the thoraco-lumbar fascia and have a more important role in maintaining stability as oppose to creating movement.

They should be the focus of your core training.

If you truly want to build strength and stay safe whilst lifting, build your TrA and internal obliques.

Altogether Now

Look. I get it.

Everyone nowadays is completely aware that the squat and deadlift trains your core. I will be the first to say, “Want a strong core? Lift heavy”.

However, there are two main flaws with this ideology.

- It’s based on the assumption that you currently possess a good level of muscular balance between your core strength and the rest of your body.

- It also assumes, that you know how to use your core effectively. For every comment said that “The deadlift works your core”, there is another comment talking about how you have to “learn to use your lats effectively”. Not everyone knows how to effectively utilise their core or any other muscle for that matter, especially the deeper (ironically far more influential core muscles – the TrA and internal obliques) whilst moving, so core specific training may be the one thing you’re missing.

Having said that, it’s important to note that the end goal should always be how to transfer your new core strength into the important tasks.

No use being able to hold a plank for 4 minutes, if your pelvis kicks under and your back hunches over, looking like a distant cousin of Quasimodo as soon as you squat.

Summary

- Core strength training refers to the ability to maintain appropriate lumbo-pelvic control, stabilise the spine and maintain postural integrity during movement.

- The antero-lateral core is comprised of four major parts: Rectus Abdominis, External & Internal Obliques and Transverse Abdominis.

- There are several reasons to want a strong core, such as injury reduction, improved cardiovascular fitness and the transfer of strength from hip to shoulder.

- Although you can’t isolate core muscles at all, you can bias exercises to increase the recruitment of some muscles. For example, a normal plank has a huge degree of rectus abdominis recruitment. Lift one leg off the ground and you’ve just recruited more of your internal obliques due to resisting trunk rotation.

- The TrA and internal obliques should be the focus of your core training if you want a greater transfer over to other strength exercises.

- The core can and should be effectively trained during dynamic movement rather than isolation. However, utilising core specific exercise can develop foundational strength and teach people how to effectively use their core strength during other exercises.

Reference List

- Alentorn-Geli, E., Myer, G. D., Silvers, H. J., Samitier, G., Romero, D., Lázaro-Haro, C., & Cugat, R. (2009). Prevention of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer players. Part 1: Mechanisms of injury and underlying risk factors. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy, 17(7), 705-729

- Barlow, F. H. (1978). Physiotherapy in obstetrics and gynaecology. British medical journal, 2(6150), 1497

- Biering-sØrensen, F. (1984). Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine, 9(2), 106-119

- Bogduk, N. (2005). Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum. Elsevier Health Sciences

- Bogduk, N., & Macintosh, J. E. (1984). The applied anatomy of the thoracolumbar fascia. Spine, 9(2), 164-170

- Brown, S. H., Ward, S. R., Cook, M. S., & Lieber, R. L. (2011). Architectural analysis of human abdominal wall muscles: implications for mechanical function. Spine, 36(5), 355

- Drake, R., Vogl, A. W., & Mitchell, A. W. (2009). Gray’s Anatomy for Students E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences

- Garvey, J. F. W., & Hazard, H. (2014). Sports hernia or groin disruption injury? Chronic athletic groin pain: a retrospective study of 100 patients with long-term follow-up. Hernia, 18(6), 815-823

- Hoffman, J., & Gabel, P. (2013). Expanding Panjabi’s stability model to express movement: a theoretical model. Medical hypotheses, 80(6), 692-697

- Kendall, F. P., McCreary, E. K., Provance, P. G., Rodgers, M. M., & Romani, W. A. (1993). Muscles, testing and function: with posture and pain(Vol. 103). Baltimore, MD: williams & wilkins

- Lee, D. G. (2011). The Pelvic Girdle E-Book: An integration of clinical expertise and research. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Pope, M. H., & Panjabi, M. (1985). Biomechanical definitions of spinal instability. Spine, 10(3), 255-256

- Rubin, B. D., & Kibler, W. B. (2002). Fundamental principles of shoulder rehabilitation: conservative to postoperative management. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 18(9), 29-39

- Vleeming, A., Pool-Goudzwaard, A. L., Stoeckart, R., van Wingerden, J. P., & Snijders, C. J. (1995). The posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. Spine, 20(7), 753-758