WHAT?

Learn the topic.

Diaphragmatic Breathing? A fancy term you may or may not have heard of. It’s a key aspect of more remedial exercise practices such as yoga and pilates, but is rarely translated over to the exercise and lifting world.

Basics

“Breathe out against resistance” “Exhale when you lift.” “Don’t hold your breath!”

Breathe out against resistance? Often the adage that is taught not only to fitness professionals, but as a result, directly to anyone who seeks advice about lifting weights. But when it comes to staying safe and being strong, it couldn’t be more wrong.

This article will show you how correctly utilising your breathing pattern during exercise will not only keep you safe, but make you feel stronger than you’ve ever been.

*NOTE = If you have any blood pressure issues, please consult a medial/healthcare professional before trying the techniques in discussed in this article.

What Choice Do We Have?

There are several breathing patterns/methods to utilise, however most within the strength community accepts that diaphragmatic breathing and holding your breath is essential for optimal performance and to reduce injury risk.

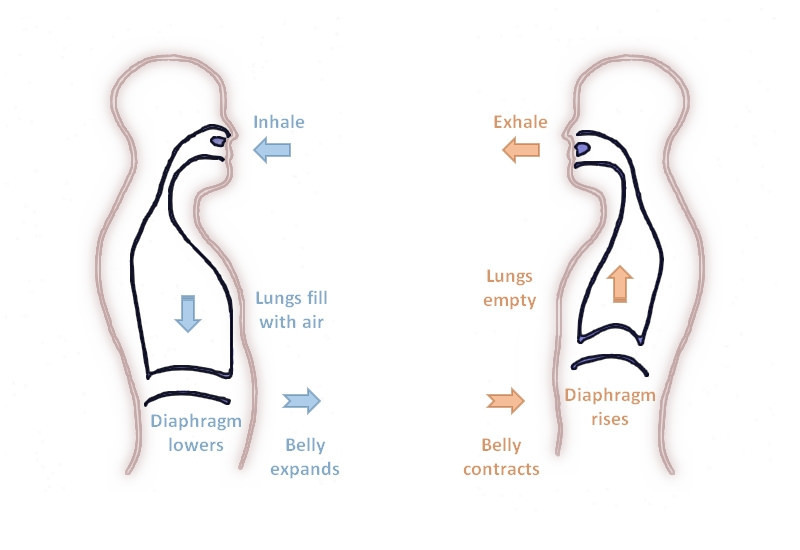

Diaphragmatic breathing involves the expansion of your stomach/abdominal region as you breathe in. Unfortunately, most people do not naturally breathe in this manner and actually do the opposite, with the stomach pulling in as they inhale and flaccidly expanding as they exhale. Try it now and see, which do you do?

Uh-oh. You’re the chest breather? Try and change it.

Struggling? Don’t worry, for many people this is actually a difficult task. You breathe involuntarily, thousands of times a day and your body has become conditioned breathe inefficiently. Now there are a host of reasons why we breathe poorly, however I’m more interested in teaching you WHY we need to breathe correctly.

If you just want to get down to the nitty gritty and learn how to breathe correctly then you can skip to the exercises shown towards the end of the article. The why however, starts now.

WHY?

Learn the science and theory.

Common Misconceptions

As with most things in fitness and training, one misconception has resulted in a “law” that simply isn’t true. Often thrown around in the gym, common knowledge would have you believe that you should be breathing out as you lift a weight, to “keep your blood pressure down” and “stop you from going light headed”. Whilst it’s true, there are extreme cases in which incredibly heavy loads lifted result in people passing out or feeling a bit dizzy, the fact is…breathing out whilst lifting is something you should be avoiding. And may be placing you in more danger than you realise.

Lower Back Pain

Breathing helps to keep the spine healthy (particularly the lumbar region), with the diaphragm being a key aspect of the core musculature that helps to provide stability (5). In fact, there is extensive research showing that breathing dysfunction can have a serious impact on lower back pain (3, 6).

Breathing helps to keep the spine healthy (particularly the lumbar region), with the diaphragm being a key aspect of the core musculature that helps to provide stability (5). In fact, there is extensive research showing that breathing dysfunction can have a serious impact on lower back pain (3, 6).

This can be explained by a model known as the Panjabi Model, with spinal stability being maintained by 3 major subsystems:

– Central Nervous Subsystem (CNS) = Control

– Osteo-ligamentous Subsystem = Passive

– Muscle Subsystem = Active

Any stimulus that interferes with these 3 systems may have a negative effect on spinal health (7).

Yep. You read that right.

Your breathing pattern (poor or great) may be significantly influencing the pain you experience either in movement, or in day to day life.

But how?

Furthermore, research into the myofascial web and intracellular matrix of the human body has found that breathing dysfunction can decrease the resting pH level of the body (creating a more acidic environment), which has been shown to increase contractility of slow acting, tension generating cells known as myofibroblasts (8). This could, overall, result in a general stiffening of the fascia in the human body (4) or, in other words, the sporadic ‘tightness’ you feel in your lower back or knee, with research showing myofibroblasts to significantly influence spinal stability (10).

Overall Posture

Another example you may be more familiar with it the classic example of how breathing restrictions such as asthma have been linked to a change in cervical spine position (also known as forward head posture) due to the body’s attempt to ease breathing and swallowing (2, 9). So if you have poor posture, your breathing pattern may be the first place to start.

Effects on Strength

You better believe it. Strength is governed by breath. World class powerlifters (such as Chad Wesley Smith and Chris Duffin) have been touting its importance for a fair few years, not only in their own performance, but the performance of the lifters they coach Recent research has directly compared different breathing manoeuvres during exercise, with diaphragmatic breathing significantly improving muscle activation and movement stability (1).

Within loaded movement, the core acts as the “transfer unit” from the force produced by the legs into the bar, not to mention providing stability for the spine. If the body senses poor stabilisation around the spinal column, it will intentionally ‘dial down’ the force it can produce to keep the body safe. Therefore, if the core is governed by the breath, you better hope you’re breathing effectively.

HOW?

Learn the implementation.

Well, first off, you need to learn how to breathe effectively. Then you need to learn how to do this properly in your lifts and in exercise/training.

90:90 Breathing

This is the first drill you need to do. Simple and effective, lying on your back with your feet up will (more or less) completely de-load your spine and pelvis as well as eliminating postural sway/balance, meaning you can focus on the task at hand. Trust me, you’ll notice when you try and do the same exercise stood up!

This is the first drill you need to do. Simple and effective, lying on your back with your feet up will (more or less) completely de-load your spine and pelvis as well as eliminating postural sway/balance, meaning you can focus on the task at hand. Trust me, you’ll notice when you try and do the same exercise stood up!

Place one hand on your chest and the other hand on your stomach. Breathe in (just steady, regularly breathing at first) and notice, which hand lifts first and then which hand lifts the most. If your “chest hand” is the answer in either of these cases, you have a faulty breathing pattern.

Although it is fine if your chest does lift, especially when you take a maximal breath, it is essential that the stomach/abdomen expands first.

Practice this exercise by establishing a rhythm in which the abdomen dominates the breathing. This is known as a diaphragmatic breath.

Crocodile Breathing

The next drill you can do is to lie flat on your front with your legs stretched out and your hands just above your head.

Press your hips down into the ground and squeeze your glutes. Then aim to take a diaphragmatic breath into your stomach, until you feel your stomach expand and press into the ground.

Bracing

Once you have this down, you need to brace effectively. After taking a diaphragmatic breath, push a finger into your lower abdomen (as shown in both photos), then using your abdominal wall, push out against your finger.

If you’re unsure how to use your abdominal wall at all, another easy way, is to push your finger into your lower abdomen, then cough hard. It’s physiologically impossible to cough without a small degree of core activation. You should feel your stomach push out against your finger. Now all you need to do, is breathe into your stomach and cough (without the cough). You have the basics of abdominal bracing down. Although it is far more complicated than that, particularly at the advanced level.

Now, it’s simply a matter of incorporating this diaphragmatic breathing pattern into your bigger exercises. The main issue is, it’s harder to coordinate when stood up, let alone during dynamic movement. Don’t believe me, do the diaphragmatic breathing drill above, then stand up and try it. Guarantee, at first, you struggle to get the same amount of expansion in your abdomen.

Low, Low, Lower Down

Here is a tip that I learned from a physiotherapist aiding with rehabilitation from abdominal surgery. To focus on the pelvic floor and lower transverse abdominis, you should also be placing an emphasis on activating as low down as possible. Main people I have come across in the training/coaching world do an excellent job of cueing the activation of their external obliques and rectus abdominis (the more superficial muscles), however with most things, true stability during dynamic movement comes from the activation/conscious control of deeper tissues.

Start off Small – Warm Ups

As I have written about before, there is more to a warm up than simply getting warm. It’s the opportune time to teach yourself and hone in on new skills, not to mention addressing postural issues of movement dysfunctions such as: how you breathe.

Perform the following in your warm up –

20 total reps of body weight squats with a strong emphasis on diaphragmatic breathing and bracing.

Remember that introducing any form of physical stress can challenge coordination, especially at first and if the stress is too great for your body to handle. Not to mention having to coordinate the use of equipment (e.g. bar position, grip width etc). Therefore, we start out with simpler exercises such as the body weight squat, to the goblet squat and gradually progress the complexity of the exercise as we become more proficient at correct and effective diaphragmatic breathing.

However, this shouldn’t take away from your current lifting routine. When ever corrective exercises are suggested, they should be used to supplement and look to improve your current routine, never to replace them (refer to this article to learn more).

Summary

– Diaphragmatic breathing is important. Not only is it a key factor that governs your potential strength but is also significantly linked to spinal stability and the incidence of lower back pain.

– Learn how to breath into your diaphragm and then brace your core effectively using the exercises shown above.

– Include these remedial breathing exercises in your warm up, followed by simple alternatives to the big lifts (e.g. goblet squat versus back squat).

– Make a conscious effort of transferring what you learn about your diaphragmatic breathing pattern, into all forms of loaded movement to maximise your performance.

Reference List

- Barbosa, A. C., Martins, F. M., Silva, A. F., Coelho, A. C., Intelangelo, L., & Vieira, E. R. (2017). Activity of Lower Limb Muscles During Squat With and Without Abdominal Drawing-in and Pilates Breathing. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(11), 3018-3023.

- Gonzalez, H. E., & Manns, A. (1996). Forward head posture: its structural and functional influence on the stomatognathic system, a conceptual study. CRANIO®, 14(1), 71-80

- Kolar, P., Sulc, J., Kyncl, M., Sanda, J., Neuwirth, J., Bokarius, A. V., … & Kobesova, A. (2010). Stabilizing function of the diaphragm: dynamic MRI and synchronized spirometric assessment. Journal of Applied Physiology, 109(4), 1064-1071

- Myers, T. W. (2013). Anatomy Trains E-Book: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. Elsevier Health Sciences

- Nelson, N. (2012). Diaphragmatic breathing: The foundation of core stability. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(5), 34-40.

- O’Sullivan, P. B., & Beales, D. J. (2007). Changes in pelvic floor and diaphragm kinematics and respiratory patterns in subjects with sacroiliac joint pain following a motor learning intervention: a case series. Manual therapy, 12(3), 209-218

- Panjabi, M. M. (1992). The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. Journal of spinal disorders, 5, 383-383.

- Pipelzadeh, M. H., & Naylor, I. L. (1998). The in vitro enhancement of rat myofibroblast contractility by alterations to the pH of the physiological solution. European journal of pharmacology, 357(2-3), 257-259.

- Solow, B., Siersbæk-Nielsen, S., & Greve, E. (1984). Airway adequacy, head posture, and craniofacial morphology. American Journal of Orthodontics, 86(3), 214-223

- Tomasek, J. J., Gabbiani, G., Hinz, B., Chaponnier, C., & Brown, R. A. (2002). Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 3(5), 349.