You’ve received your training plan.

You open up the document and see a whole host of exercises sprawled on the page in front of you – when the first decision comes into play…

What Exercise Order Do I Follow?

Your plan says a heavy set of deadlifts are due – surely you don’t want to waste any energy before hitting those?

Although what seems to be a simple issue, it can quickly manifest itself into a pretty big barrier for some, particularly when faced with the constraints of time and availability.

Not only that, it can actually have a marked effect on your performance and gains as a result.

Exercise Order doesn’t really need a definition – it’s the order in which you choose to perform them.

And despite there being a pretty clear-cut structure within most training regimes, they are open to manipulation based on a few factors – let’s discuss what they are.

*Quick Disclaimer – if you have a coach, chances are they have laid out your exercise order as part of the program design, so consult directly with them if you feel you need anything changing, or leave it as is!

HOW?

Learn the implementation.

1. Specificity / Priority

This section largely depends on whether or not you’re planning on competing in sport at any level. If you are, then the exercise with the greatest carryover to your athletic performance is probably best going at the start, when you’re fresh from a physical and cognitive standpoint.

Specificity in the gym itself is particularly important if you are competing in powerlifting or any other form of strength sport. If you are being physically tested in one specific exercise, then you should rate that at the start of the exercise order list.

Is this always the case? Well, regardless of the training plan you follow, it’s almost unanimously agreed that specificity should increase the closer you are to a contest – with the specific exercise forming the foundation of the training session.

If you are off-season or a good few months away from any form of test, then it stands to reason that the demand for specificity is lower, in which case you can adjust the exercise order, so that movement occurs later, if the other variables are more pressing.

2. Neural Demand

At the risk of running full geek mode – Neural Demand is next step to consider when considering exercise order.

When talking about anything Neurological, we’re referring to a few different things:

- Motor Unit Recruitment

- Firing Rate

- Neurotransmitter Release

- Psychological Arousal

Covering them in detail is beyond the scope of this article, but it’s important to be aware that each of these factors contributes to how taxing a movement can be on the Neurological System.

With that in mind, there are 2 Primary Training Variables that determine the level of CNS Recruitment and they have a fairly intricate relationship:

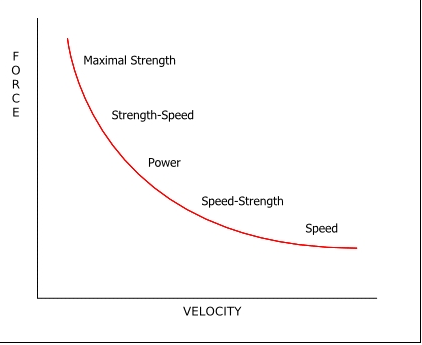

Force and Velocity

Keeping it super simple – here is an oversimplified version of something known as the Force Velocity Curve below:

2A. Speed + Skill

Provided that you’ve already made the decision on specificity – as a rule, the faster a movement occurs, the earlier it should be in the exercise order.

This is because the Neural Demand for high-velocity movements is so much higher than in any other task performed by the human body.

Contrary to popular belief in the fitness world, lifting heavy and training to failure don’t even get close to the neural demand of high-speed training.

World-Renowned sprint coach Charlie Francis was often quoted for saying that sprint training occurs “FAST or SLOW”, with nothing in between (Francis, 2012, 2013). In fact, his emphasis on Intensity for Speed was so heavy, he would monitor his athletes and physically stop their training sessions if they were “out” by a few fractions of a second.

DAYS TO COMPETITION | TRAINING PRESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

10 Days | Spikes on track: 4 × 30 m from blocks with full recovery. 80-100-120-150-m flying sprints with maximal intensity, full recovery (i.e., 20–35 min between sprints) |

9 Days | Trainers on grass: 10 × 200 m tempo runs with 100-m walking in between |

8 Days | Spikes on track: 4 × 30 m from blocks and 1 × 120 m at 95% intensity, full recovery |

7 Days | Trainers on grass: 2 × 10 × 100 m tempo runs with 100-m walking in between |

6 Days | Spikes on track: 4 × 30 m from blocks and 1 × 150 m at 95% intensity, full recovery |

5 Days | No training |

4 Days | Spikes on track: 4 × 30 m from blocks and 1 × 80 m at 95% intensity, full recovery |

3 Days | Trainers on grass: 10 × 100 m tempo runs with 100-m walking in between |

2 Days | Spikes on track: 4 × 30 m from blocks at 95% intensity, full recovery |

1 Day | No Training |

At the risk of sounding reductionist – there’s a reason most sprinters look like this…

The neuromuscular demand placed on the human body is leagues beyond almost anything we can replicate in the gym. From the impact on bone tissue, to the neuromuscular recruitment – there are few things that come even close.

Find Out Yourself...

Now I wouldn't recommend diving into high speed sprinting straight out of the gate - the skill demand is fairly high. Instead, choose something with a fairly low skill demand that you can perform at high speeds in the gym. A classic example is a maximal effort jump.

After warming up appropriately, perform a maximal effort jump and record the height.

Then spend a decent chunk of time, aiming to replicate that same effort.

I can almost guarantee, you will hit it once or twice more (maybe even surpass it a little), then once fatigue sets in, the drop-off will be remarkable.

Another even easier test, perform 5 consecutive jumps. By the 5th jump, it will feel like you're hardly leaving the floor.

A Few Examples of High Speed Movements in Training

BONUS – Potentiation

To add to the idea of speed being trained first to capitalize on neurological readiness – I want to introduce you to the concept of ‘Post Activation Performance Enhancement (PAPe)’.

Originally coined Post Activation Potentiation it is a phenomenon by which the force exerted by a muscle is increased due to its previous contraction caused by phosphorylation of the myosin-light chain filaments, showed an increased twitch-invoked force production (Blazevich et al., 2019).

Since then, researchers have more appropriately measured the direct effect on performance (PAPe) due to other possible explanations such as changes in muscle temperature, calcium ion concentration and more which still remain unexplained (Blazevich et al., 2019)

Irrespective of the direct mechanism, it is a theory that states the contractile history of a muscle influences the mechanical performance of subsequent muscle contractions (Robinz et al., 2005; Lorenz, 2011).

To put it simply – performing a movement that stimulates the nervous system, prior to completing another task, will result in improved performance.

Now, the majority of research shows PAPe taking place with heavy loads being lifted prior to high-speed movements, but we also know that the opposite is true (Beato et al., 2021), applying perfectly to any scenario in the strength and lifting world!

So provided it doesn’t negatively affect the 1st rule of specificity, in many instances performing your higher velocity movements at the start of a training session, may actually enhance your strength later on in the workout.

2B. Absolute Work

This is the next step to consider when it comes to the exercise order in a training session.

Notice – it’s not absolute load.

Just think logically. You could leg press 400kg, but squat 300kg. I think anyone with experience of both movements could safely assess that the squat is more taxing than the leg press.

‘Work’ on the other hand, as the biomechanical definition states is:

A product of the force x displacement of the external load.

In other words, it’s the combination of load being lifted AND the range of motion over which the weight is being lifted, that creates the fatigue response.

Although it’s not an extensively researched area – there are a few very interesting articles that show this to be the case.

In fact, a recent article challenged the popular claim that “Deadlifts are more fatiguing than squats” and directly tested the fatigue response of both exercises (Barnes, 2019). And in this instance, they actually found the opposite to be true – when assessing both central and peripheral fatigue – they found no differences with central fatigue and actually greater peripheral fatigue in the barbell back squat (Barnes et al., 2019).

Despite the heavier load being lifted in the Deadlift for all participants, they theorized that the best explanation for this was due to the larger amount of mechanical work done in the squat, relative to the deadlift for those individuals.

Now, taking this with a pinch of salt, it doesn’t mean that the squat will always be more tiring for you. You have to factor in that most people lift more in the deadlift (unlike the subjects in this study) and more importantly, the efficiency of technique plays a big role.

But the point still stands – both load AND range of motion forms the WORK being performed, which is the primary factor.

And even without the empirical data – we see this observation regularly in the gym.

Squats are more tiring than leg press.

Sumo Deadlifts are less fatiguing than conventional deadlifts for most, due to the shorter range of motion and lower work done as a result (Escamilla et al., 2000).

PRACTICAL THOUGHTS

There's a clear distinction between TRAINING and TESTING.

If you're new to the World of Strength, then you may not have objected to the above.

Chances are however, if you're familiar with lifting you will have come across the notion of max effort lifting creating CNS fatigue and much more besides. While there is still ambiguity surrounding this topic, a key takeaway is that we're discussing training - which in most cases, shouldn't involve maximal weights.

One final thing to consider is the trained state of the individual. If you're a powerlifter, then no - a power clean when you first start out, probably isn't going to fatigue you as much as a working set of deadlifts. But the limiting factor in this situation is the skill of the movement.

Choosing exercises where the skilful execution isn't the limiting factor and in a training environment, the faster the movement - the greater the neural recruitment.

3. Weak Points

As I’ve spoken about before using the “Layer Theory”, if glutes are your weakness, they should receive a higher priority in the exercise order.

Get them out of the way, chances are you’re going to skip on them or conveniently “run out of time” when it matters most.

Weaker areas typically also create larger amounts of fatigue, at least in the early days – as they are much more mentally taxing as well.

The only time “Weak Point” training shouldn’t go first, is if and when it interferes with the two, previous rules.

For example – if you have heavy squats and your quads at your weak point, don’t go and train 4×10 on the leg extension before putting a barbell on your back. In most cases, the back squat will still be deemed the more “specific” movement in that training session, so it should occur first anyway – but it’s still worth mentioning to avoid confusion!

This can actually be leveraged to great benefit in a training method known as “Pre-Exhaustion” – a training technique that will be described later in the article.

Usually, the things we should do, that will improve our results and set us up for long term progression, also happen to be the things we hate doing.

5. Metabolic Demand

The final rule for Exercise Order considers Metabolic Demand.

This section typically refers to hypertrophy, prep and conditioning work but also has a bearing on your entire training plan.

The longer the duration, the higher number of repetitions, the lighter the load – the further along in the training session the exercise should take place.

Although acute fatigue is high, provided the load isn’t excessive (which in most cases for this type of exercise, it isn’t) it’s usually fairly easy to recover from and the injury risk is low.

This is where you can safely and effectively slot in what are often known as ‘bodybuilding intensifiers’.

- Supersets

- Giant Sets

- Pre-Exhaustion etc.

They’re all incredibly effective methods of increasing the total volume of work done, correcting muscular imbalances and increasing muscle mass.

*Bonus Point = It will also improve your training economy and the pace at which you can complete your workout. Spending less time in the gym and gaining the same amount of progress.

Cardio vs. Lifting

It's forever a battle between which should come first - cardio or lifting?

Conditioning for strength athletes has always been something people have struggled with but as with almost all questions asked... it depends.

Largely on two things -

- What intensity are you working at with your cardio? - Is it high-intensity interval training and classed as conditioning for strength athletes or slow cardio that hardly raises your heart rate?

- How heavy are you planning on lifting?

A Case for Cardio First

If you're planning on working at a lighter, slower pace for a longer duration (i.e. the typical aerobic training), you would be much better off performing cardio first.

This for 3 reasons:

- You're not working hard enough to cause lots of fatigue prior to training.

- You're going to provide a pretty sufficient warm-up (which is something far too many people skip!) before lifting anything heavy.

- Excessive amounts of long, slow cardio after lifting suppresses a neurotransmitter known as mTOR (Ogasawara, 2014) which is a key trigger for the anabolic process of building muscle. Essentially, you would "cancel out" a chunk of the potential gains made from lifting.

In addition, if you are performing the longer, slower aerobic exercise first, it has been shown to have no negative effects on muscle hypertrophy (Lundberg, 2014).

Now it's important to note on that last point - this would only apply if you were planning on doing slow, aerobic training for more than about 15 minutes. The catabolic ('breaking-down') process that occurs from long bouts of aerobic training only kicks in after a certain length of time - high-intensity cardio is a little different.

Which leads me on to...

A Case for Cardio Last...

If you're performing high-intensity forms of cardio, you're much better performing this towards the end of the training session.

As noted above, the fatigue element is quite a big factor. Meaning that if you are planning on hitting some heavy conditioning right at the start of the session - you run the risk of negatively affecting your performance when doing the stuff that really matters; lifting.

To add to that, high-intensity cardio (particularly the type referred to as conditioning with external resistance) doesn't necessarily result in the mTOR suppression we saw earlier - meaning you can happily leave the cardio to the end without it affecting your session.

Just remember...don't skip it every time.

References

- Barnes, M. J., Miller, A., Reeve, D., & Stewart, R. J. (2019). Acute Neuromuscular and Endocrine Responses to Two Different Compound Exercises: Squat vs. Deadlift. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 33(9), 2381-2387.

- Beato, M., Stiff, A., & Coratella, G. (2021). Effects of postactivation potentiation after an eccentric overload bout on countermovement jump and lower-limb muscle strength. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 35(7), 1825-1832

- Blazevich, A. J., & Babault, N. (2019). Post-activation potentiation versus post-activation performance enhancement in humans: historical perspective, underlying mechanisms, and current issues. Frontiers in Physiology, 10, 1359

- Escamilla, R. F., Francisco, A. C., Fleisig, G. S., Barrentine, S. W., Welch, C. M., Kayes, A. V., … & Andrews, J. R. (2000). A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 32(7), 1265-1275

- Lorenz, D. (2011). Postactivation potentiation: an introduction. International journal of sports physical therapy, 6(3), 234

- Lundberg, T. R., Fernandez-Gonzalo, R., & Tesch, P. A. (2014). Exercise-induced AMPK activation does not interfere with muscle hypertrophy in response to resistance training in men. Journal of applied physiology, 116(6), 611-620

- Robbins, D. W. (2005). Postactivation potentiation and its practical applicability. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 19(2), 453-458

- Francis C. Structure of training for speed (ebook). https://www.amazon.com/Structure-Training-Charlie-Francis-Concepts-ebook/dp/B00BG9F8UG. Assessed 24 Nov 2021.

- Francis C. The Charlie Francis training system (ebook). https://www.amazon.com/Charlie-Francis-Training-System-ebook/dp/B008ZK0WR8. Assessed 24 Nov 2021.

- Ogasawara, R., Sato, K., Matsutani, K., Nakazato, K., & Fujita, S. (2014). The order of concurrent endurance and resistance exercise modifies mTOR signaling and protein synthesis in rat skeletal muscle. American Journal of physiology-endocrinology and Metabolism, 306(10), E1155-E1162