| Mental Toughness – Think Yourself Stronger |

Mental toughness is an aspect of fitness that's often overlooked - yet may hold the secret to keeping you on track towards your goals and smashing through training plateaus. Let's dig…

Mental toughness is an aspect of fitness that's often overlooked - yet may hold the secret to keeping you on track towards your goals and smashing through training plateaus. Let's dig…

Loaded carries may be the missing link in your training; they are the way to building the ultimate, strongest version of yourself. Simply grab a weight and walk. Here's why.…

Eccentric Training How long have your numbers been stuck? How long have you been riding the latest plateau in training, waiting to see when you'll see the progression you're after? …

Set the Scene Struggling to decide what core exercise is worth your time? Kath felt like she tried everything to get her towards her goal of bringing up her squat.…

There's still a debate raging about isolation exercises vs compound. Which is the most effective for strength development and when/where are they appropriate? As is often the case, the answer…

For an even more in-depth look into the world of deadlifting, head on over and grab a copy of your free EBook – “The Deadlift – 8 Steps from Start to Finish”.

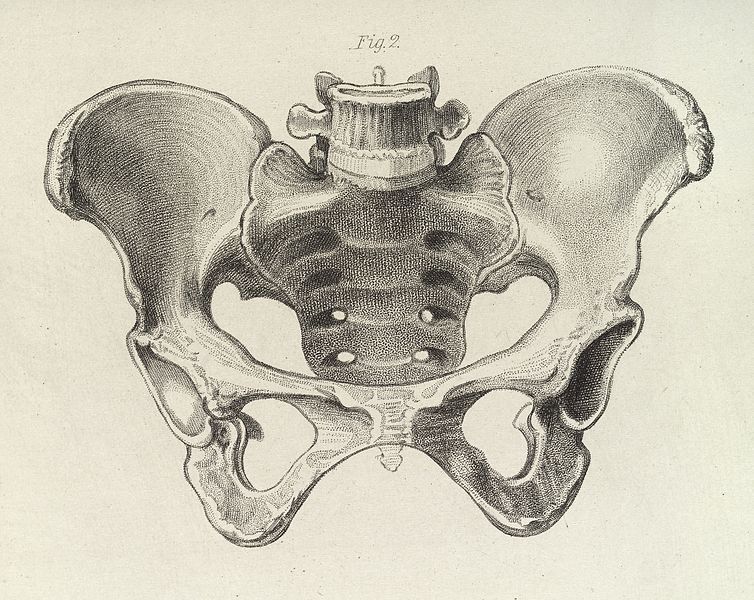

Holy hip mobility. You walk into the gym and see someone deadlifting with the widest stance imaginable. I mean, how in gods name are they stood so wide? What’s the point? Suddenly, you start asking questions and wondering if you’ve been “doing it wrong” or missing out on something golden this whole time. And the answer is, the sumo deadlift.

Chances are if you haven’t heard of powerlifting, you may not even be aware of what the sumo deadlift is. Or that there even is a difference. After all, almost all fitness classes only teach a poor derivative of the Romanian deadlift or conventional stance. And when ever people do perform something that looks like a sumo deadlift, it’s more likely to be a wide stance squat.

But fear not…this article will clear up the confusion and give you all the take home information you need to determine whether or not sumo deadlifting is the way to go.

Learn the topic.

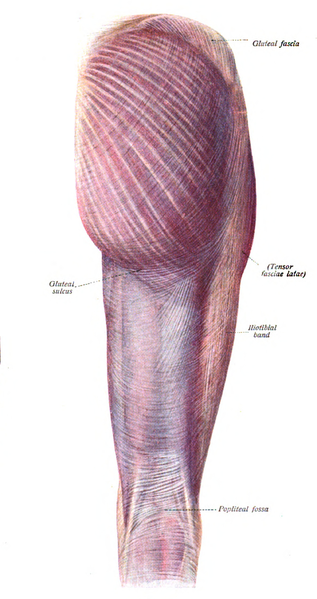

First off, we need to cover what the sumo deadlift is and what it entails. The sumo deadlift is a lift characterised by a wider stance (usually well outside shoulder width and determined by your height, femur length and overall mobility), with the hands and grip placed on the inside of the legs.

This results in something resembling the following:

As is the case with the conventional deadlift, it is more or less every muscle in the body in one way or another.

However, if we compare the sumo deadlift to the conventional, research has shown key differences to occur with muscle activation of the upper back (trapezius) and quadricep muscles (3), with much lower activation of the erector spinae and hamstrings.

The sumo deadlift brings with it, 3 major benefits over the conventional deadlift:

This is a biggy one of the best rationales for performing the sumo deadlift (although not as simple as you will see towards the end of this article), but for most the sumo deadlift is much friendlier to those that suffer from back pain.

Although the conventional is still a fantastic lower back management tool, no matter how we look at it the sumo is a bit more friendly, with significantly lower lumbar compressive forces being reported (1).

This is a widely spoken debate in the world of lifting as to which lift trains the glutes the most. Research has shown that there is no significant difference to be found (3) between sumo or conventional.

However, there are two main things we need to mention here.

It appears there’s a bit of an epidemic at the moment, of people being unable to effectively activate their glutes. We won’t be discussing why, but how to effectively switch them on.

To effectively train any muscle individually, or to improve the mind muscle connection, it’s important to know what, and to perform, all the movements it is involved in. The glutes for example, don’t simply extend at the hip. They also create abduction (taking the leg out away from the body) and external rotation (turning your leg outwards). When performing the sumo deadlift, all 3 principles are performed simultaneously.

Now you could rationalize that all 3 principles should be performed in the conventional deadlift. That is a good point, they should.

However, it is also much easier to feel a muscle working at the extremes of length (i.e. in a stretched position or a shortened one).

For example, do the following exercise:

Hold your arm down by your side and tense your arm.

Then slowly (as if lifting a really heavy weight) bend at the elbow. Keep bending until right at the top (tensing your arm throughout).

You will have “felt the bicep” the most, right at the top position.

To return to the deadlift, when in the sumo stance, because of wide foot position, your legs are already “abducted”, meaning the glutes are partially shortened and as a result, people tend to feel them a little more.

Also try the following exercise:

Stand up with your feet in your conventional deadlift stance. Squeeze your glutes as hard as possible.

Then take your feet out wide (into a sumo stance), rotate your feet out to about 30 degrees and do the same thing. Chances are, you will feel your glutes tighten much more on the second example.

Now this sounds like I’m misleading you a little but bear with me.

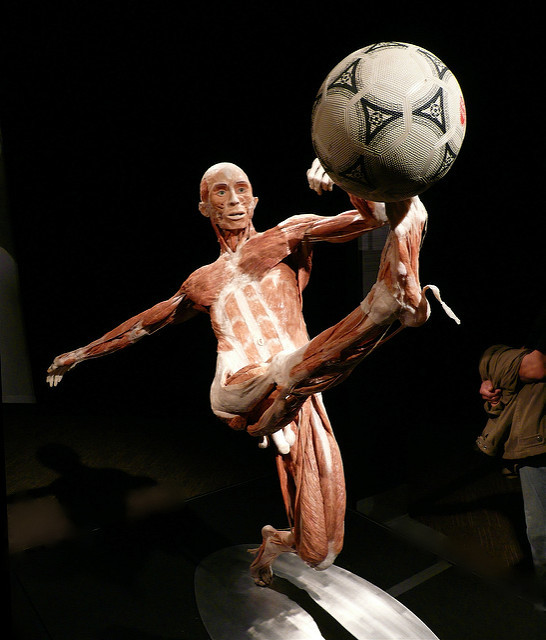

This is where the idea of movement and the study of anatomy blend into an irritating, hard to explain grey area.

With the majority of early research on muscle tissue done either on cadavers (dead people) with electro-stimulation right through to research done on live subjects today in isolated motions, the study of a muscle is just that. The muscle.

Unfortunately, technological and methodological limitations often hinder the ability to study the muscle during active locomotion.

Thankfully however, there are a few that have done the pain staking work of delving into insane levels of depth by the like of Thomas Myers over decades of studying have found that the actions muscles can create, isn’t what they create in every day movement.

And this is where the glutes come into a play. Even though the glutes can create hip abduction, in every day life, they perform this action more commonly by “resisting adduction”, i.e. preventing the leg falling towards the midline.

Our most primitive form of movement is in walking. All our developmental stages in life lead us towards the most efficient form of gait cycle seen throughout the animal kingdom, the human walking pattern. When we take a step forward with our left leg and support ourselves with our right leg…It is the right glute (and the left quadratus lumborum) that prevents our pelvis collapsing, our torso leaning to the left and us falling over (4).

When performing the sumo deadlift, the action of “abduction” is actually manifested as “resisting your knees being pulled inwards/adduction”. And although again, you do also perform this in the conventional deadlift, the wider stance challenging this motion to a much greater degree due to the changes in length tension of the glutes we mentioned earlier.

As a result, there is actually rationale for using the sumo deadlift to improve a faulty gait pattern.

And this is why most people refer to the sumo deadlift as “cheating”.

Not only common sense (from watching how far the bar moves) but scientific research has confirmed the sumo deadlift to result in an average of 25-40% less mechanical work/effort is required to move the same load (2).

This is simply because work = force x displacement.

The bar doesn’t move as far. It’s that simple.

Learn the science and theory.

So why do different muscles activate and why do we get these benefits?

“The greater the distance from the pivot point = the greater the moment arm = the more force can be/is exerted.”

We don’t have to get too complicated really.

When you lift a weight, you both become part of the same system. Excuse the cliché, but you and the weight literally become one.

Now you are applying force to the weight, but it also applying a force directly back at you (in the form of it’s mass (kg) x gravity (9.812)).

If you imagine in this instance, that your spine is a screw that is being undone.

Your spine is literally being turned inwards and collapsed by the weight you are lifting…what happens when you use a longer spanner/wrench to undo a tight bolt?

The longer moment arm means you can undo the same bolt with less force. Or, you can undo a tighter bolt with the same force.

The same is true with how the bar acts on your body. The same weight, is going to have a much easier job of bending your spine in half so you look like a dog taking a dump when it is way out in front of you; than it would if you kept it closer to the body.

That’s it. Physics lesson done. I won’t even delve into individual moment arms for each joint.

We can go into that in more detail at a later date, but for now, that’s all you really need to know.

Within the sumo deadlift, the wider stance gives you a much broader base of support. This allows you to assume a much more vertical torso position relative to the barbell and as a result, unless you struggle with hip mobility, then the bar should be closer to your hips (i.e. the pivot point) within the sumo vs. the conventional.

And within the research our good old pal, Escamilla and Co. returns again for another research paper to show the key biomechanical differences, finding…

“The sumo group had 5-10 degrees greater vertical trunk and thigh positions, employed a wider stance (70 +/- 11 cm vs 32 +/- 8 cm) and turned their feet out more (42 +/- 8 vs 14 +/- 6 degrees)” – Escamilla et al. (3).

So we know that the vertical torso position, closer hip position and changes in muscle activation favouring the legs and upper back is gained from performing the sumo deadlift.

Why the hell don’t we always sumo deadlift?

This is where individual anthropometry comes into play (boom…word of the day right there).

This refers to the bodily structure of a person, such as the limb length, natural joint position etc. Although this is often used to dismiss poor movement as “individuality”, it does have a minor role to play when deciding which lift is best for you.

For example, if you’re someone who has excessively long femurs (length from your hip joint to your knee), you may have a hard time deadlifting in a conventional stance. This is simply because of the distance the bar will have to be positioned during the setup, relative to the hip joint. Meaning, you may be better off in a sumo.

If you have longer arms and shorter femurs (god damn you), then chances are you will be able to make light of deadlifting the world in a conventional stance without too much effort.

HOWEVER…

This is one of the situations where individual comfort comes into play. There are quite a few exceptions to the limb length rule, largely because of pelvic structure. Everyone’s pelvis is built differently, and some will prefer a wider stance over another.

Without going into too much detail (after all, you’re probably not going to go and get an x-ray to discover what your hip joint looks like relative to your pelvis), it’s important to note that the easiest way to tell which is best for you, is to perform both for a few months and see which feels more comfortable.

For example, I love conventional deadlifting. I used to dismiss the thought of the sumo stance, until my first ever session where I hit my 5kg above my conventional max (225kg at the time) without anywhere near as much effort. Since then I’ve continuously rotated them both, but clearly I am naturally stronger in the sumo stance.

Although there is no direct, published research on this topic, I spent a large portion of undergraduate and postgraduate studying to investigating the deadlift and found one thing – impulse is everything.

Impulse = force x time (i.e. the amount of force you can apply x how long you’re able to apply that force)

In order to overcome the inertia of the bar (the fact that the bar wants to stay glued to the ground), you have to generate a huge impulse.

Now, because the conventional deadlift is a much more natural position for most (versus standing incredibly wide), it is much easier to generate this impulse. You tend to be able to generate more force straight out of the gate, and therefore don’t have to spend as much time pushing into the ground.

HOWEVER…

This is where most people go wrong in the sumo deadlift. Due to being unable to apply force at the same rate, you have to push for longer (sounds odd I know, but if you want me to bore you with the Impulse-Momentum relationship, you need only leave a comment below).

Most people…don’t like being uncomfortable for too long.

So what do they do?

They push for a little, then say, “F this”, break their form, their knees cave in and their back rounds slightly (which ironically shifts the technique towards the starting position of a conventional deadlift).

The weight rushes off the ground, and then they get stuck at lockout.

The same thing happens with all forms of deadlifting. But it is much more prominent in the sumo deadlift, because you have to apply force for longer to get the weight moving.

This is what most people refer to as the “skill” element. As well as a whole host of other factors, this is the most common area where people go wrong.

Learn the implementation.

Check List:

The rest of the points can be found, in a free copy of our E-Book:

“The Deadlift – 8 Steps from Start to Finish”

The conventional deadlift and sumo deadlift both possess key differences such as:

However, they are largely the same movement.

Just when you thought it was over…the nerdy stuff makes a return at the last minute. This is actually the only real “beware” point I can think of when sumo deadlifting…but it’s worth mentioning.

Bear with me…

Significant weakness in the core, results in high tone of the muscles that attach to the same apoeneurosis namely the adductor magnus/groin (7) and hip flexors.

This excessively high tone can result in reciprocal inhibition (decreased activation) of the glutes (5).

This means the glutes don’t work properly to effectively abduct/resist adduction at the hip, or to produce the hip extension (6).

This may result in a sub-optimal position in which you either can’t get into the upright torso position (due to lack of mobility) or you have the hyper-mobility, but lack the appropriate stability from the surrounding musculature to stabilise your pelvis and lower back.

In this instance, you will ultimately end up rounding your lower back and experiencing similar compression as you would in the conventional deadlift, but you’ve also stretched your hip joints under load with very little stability.

Basically, just because the sumo deadlift is closer to the hip and “doesn’t load your lower back as much” doesn’t mean you can get away with having a weak core. Make sure you’re building your core in the mean time.

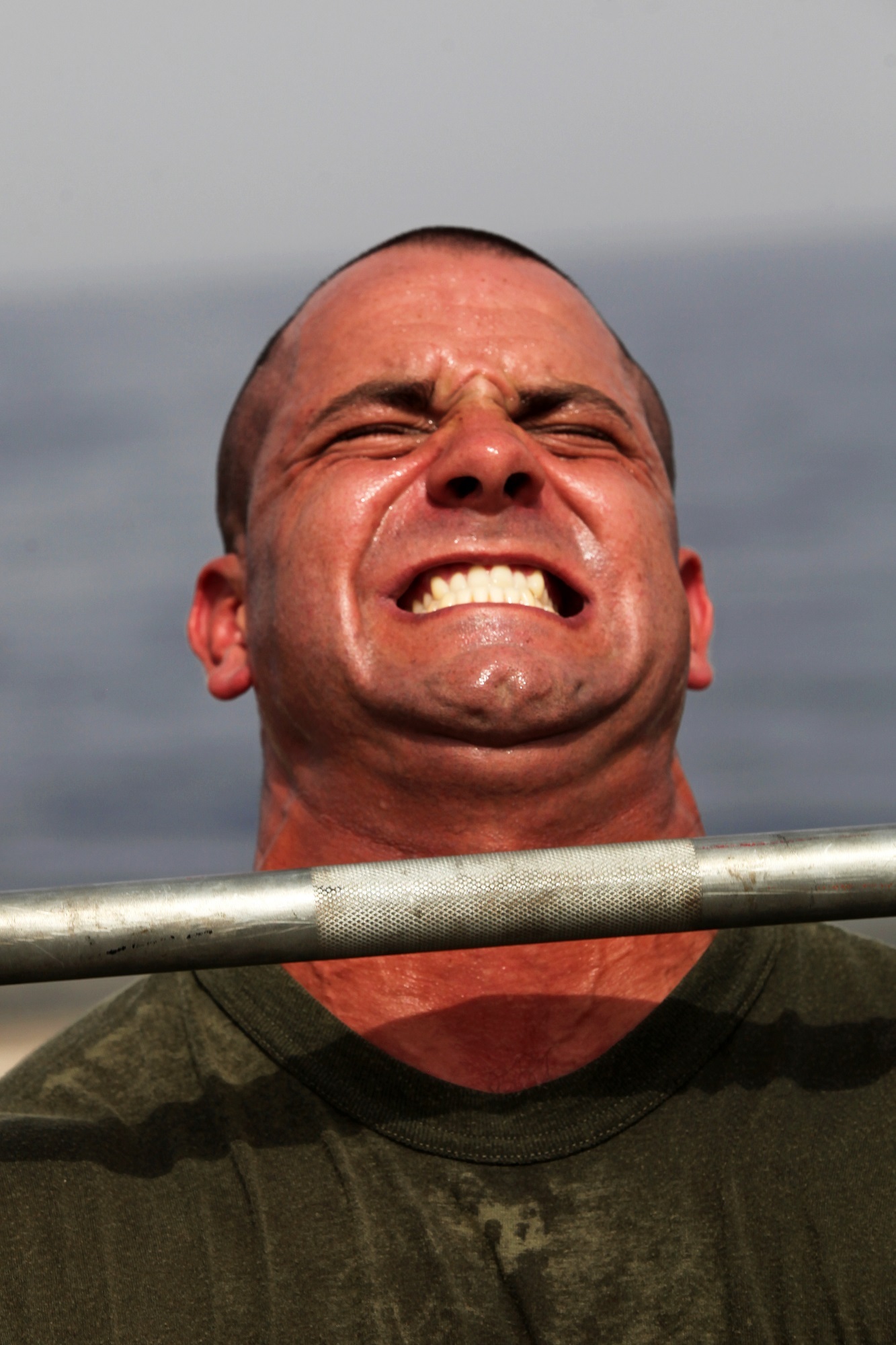

Training to failure. The strange sadistic pain that you either learn to crave or learn to hate when it comes to exercise. The burning sensation, searing through muscles you didn’t even know existed…whilst the small voice inside of you (or the voice of your trainer) screams at you to keep pushing; beyond what you thought was possible; working and training to failure.

You have put the work in, it’s time to put the weight down and rest.

But hang on, you look around and see others in the gym, lifting until they physically can’t lift anymore. You see people training to failure in every exercise imaginable. Needing spotters for the last few reps before they slam the weights down after being defeated. Or succeeding in training to failure? Who knows.

But you find yourself wondering, am I not pushing myself enough? Should I be training to failure like others around me?

Learn the topic.

Training to failure was once the hallmark of the lifting world. With bodybuilders and other fitness professionals heralding it as the key to maximising muscle growth and progression. But have things changed and should we be training smarter as a result?

Training to failure, also referred to as ‘volitional failure’ refers to the inability to sustain an activity due to exhaustion/fatigue. More specifically in reference to lifting, we’re referring to the inability to sustain concentric contraction…or in other words, you can no longer lift the weight you are aiming to lift.

Well straight out of the gate, just think about it logically. We live in a world where we’re constantly told to, “Never Give Up!”, swarmed by the array of motivational quotes about there being “No Plan B” and so on.

In addition to that, we’re told from a young age and throughout life, that the more effort we put into things, the more we will gain as a result.

This behaviour largely stems from our evolutionary biology and our Darwinian relationship with the rest of nature. It’s all about survival…and what does that entail? Working your arse off and continuing to push until you either succeed or die.

In the Western World, a large portion of our fitness, exercise and health knowledge initially came about due to both the 1st and 2nd World Wars, in which we looked to develop the fitness and physical potential of our soldiers.

It’s not surprising then, to find that there are a few lessons carried over from military style training into our current approach to exercise. You only need to look at your local leisure centre to find words like “Military Fitness” or “Bootcamp” to see this message resonate through.

Obviously, with this came the idea that we need to select only the toughest among us. Which meant, push until you can’t push no more. And this ideology, combined with certain bodybuilding philosophies has resulted in this, “Don’t leave anything on the table” kind of mindset.

This is where I play the devil’s advocate. When looking to build muscle, it is a very costly process for the body to be in an anabolic state for long enough to form new muscle tissue. The idea being then, that you need to provide enough of a stimulus and have the right building blocks in place.

Think about when you’ve ever built an piece of furniture from IKEA. I can provide you with the raw materials (i.e. the shelves, the screws etc.) or in other words, the appropriate stimulus of lifting weights, but if you don’t have the instructions on how to do it (i.e. adequate protein intake, lots of sleep etc.) then you’re going to have a hard time ensuring you built the damn thing correctly.

Then flip that on it’s head. If you had all those other lifestyle factors in place and an appropriate sympathetic to parasympathetic balance, but didn’t have enough of a stimulus (i.e. the pieces themselves) then you’re definitely not going to build anything.

This led people to the idea that, “Well if I train to failure, then at least I know I’ve not left anything behind”. I’ve got more than enough pieces to assemble the muscle.

But is that the way it actually works?

Before we delve into the research too much, there are at least some benefits to be drawn from training to failure. It’s hard to argue with some of the greatest bodybuilders in the world (who also possess phenomenal strength), that it simply doesn’t work, no matter what.

The question is, is it necessary, effective or even a contributing factor to the results they achieve?

Training to failure, does bring a couple of benefits that people believe such as:

If you are someone who does not shy away from the concept of working hard, then this point isn’t referring to you.

But let’s face it, there are many people who partake in exercise who, initially don’t possess the grit and gristle that most people assume you need to lift weights. As exaggerated as it may sound, training to failure on occasion can show you who you really are and how you react when placed under immense stress.

As you will read about shortly there is a bit of research to support the notion that training to failure does improve strength (although it’s far from that simple).

To add to this, the advocates of training to failure (or a least fatigue) use the argument of the Repetition Effort Method (RE) coined by Professor Zatiorsky (16). This initial idea stems from the Hennemann Size Principle in which when you lift a light load, as motor units’ fatigue, larger ones are recruited in their stead to maintain the force required to lift a weight (7).

*Note – Improvements in strength that do occur from failure training, may very well come from the idea that you’re simply working harder. Remember, effort and intensity are two entirely different things and where you may be thinking you’re pushing at 90%, you may actually be under performing significantly in training.

As I have written about before when referring to the 3 Methods to Muscle, there is a huge amount of support for the use of failure training to increase the amount of metabolic stress that occurs and therefore, a mechanisms for building muscle mass as a result.

Learn the science and theory.

Failure occurs for a very simple reason…fatigue.

Demand for energy to sustain an activity far outweighs supplies that can capably be provided by the body.

There are several types of fatigue, namely: Metabolic/muscular, endocrinological/adrenal and neurological. It’s rare that you will ever push yourself to the extent that neurological or adrenal fatigue are the limiting factors (unless you have been lifting far too heavy, far too often and disrupted your nervous system regulation), so metabolic/muscular is the main focus.

It’s essential to consider your own individual situation here. If you are a professional athlete who dedicates every waking moment to your performance (and doesn’t worry about anything else), then you can probably get away with training to failure a little more often. It won’t cause a huge amount of change. This unfortunately is where the issue tends to lie.

Most of us (myself included) when looking to improve muscle strength or size, turn to what the elite do. Bodybuilders may train to failure on a regular basis, but then have a full time job of handling their nutrition and recovery. So, we assume that we can do the same thing as them in the gym, yet have everything else going on in our lives that gets in the way.

And ironically, that’s only in reference to building muscle. When you speak to or research recommendations given by the strongest athletes on the planet, I can almost guarantee that non of them will recommend training to failure and that you should always stop a few reps shy.

If you’re anyone else besides an elite athlete, the research just simply doesn’t support the notion of “training like a beast” all the time (i.e. training to failure). Research has shown experiencing the other stresses of life, such as being at school, can directly impair your strength development (2) and increase your injury risk (9).

Now, true, I have spoken about the ability to utilise other exercise modes to facilitate your recovery and therefore not necessarily needing a de-load.

However, that refers to a situation when “normal” training (i.e. training that pushes you but not too the absolute limit) being a stressor.

When you then include a form of training such as training to failure, the sheer magnitude of your effort is more or less guaranteed to tip the scales a little too far in the direction of imbalanced training and recovery, regardless of what you do on the outside.

This has led to many researchers’ state that training to failure may be the cause of many states of overtraining and overuse injuries (13) in a wide array of sports.

Now I admit, this is quite a soft comment and maybe I’m being a bit too nicey nice nowadays. But one of the huge barriers to get people to lift weights and engage in forms of exercise to make them healthier, is that they are exposed to the cult-like “Never Give Up, Never Surrender Mentality”. As mentioned at the start of this article, this leads people to believe that training to failure and pushing to the point of pain is the only way it can be done.

However, this simply won’t work for the more sensitive among us. And it doesn’t have to either.

“Pain changes Movement” – Gray Cook

Contrary and irrespective of what people would have you believe, pain changes the way you move. Unless you think you can completely override your body’s inhibitory, protective mechanisms (which is nigh on impossible), you can’t perform the same motor pattern when you’re experiencing significant amounts of pain.

Furthermore, pain is an entirely subjective experience (4). I may be quite soft on people here but when one-person training to failure may only experience discomfort, others may register it as pain…Altering their ability to effectively execute the task. A recent meta-analysis by Bank et al. (1) investigating the effect of joint/muscle and tendon pain on motor control concluded the following:

“Collectively, the findings show that experimentally induced limb pain may induce immediate changes at all levels of motor control, irrespective of the source of pain”

Now the key here, is I’m not stating you will be at a greater risk for injury. Although I do believe that’s a possible downside, there is no actual direct evidence to suggest that your injury risk is greater when performing sets to failure.

However, it does affect your ability to execute the same motor pattern efficiently and therefore, may not be as beneficial when looking to truly build your strength in the long run.

Alright tough guys. I get it. Talking about an inability to recover, pain and being soft might not compute with you. After all, the pain you experience in the gym can be half the pleasure, right?

Well I’ll give you another argument instead then:

Training to failure is not as effective as non-failure training for strength.

There is an ever-growing amount of literature showcasing non-failure training to be superior for strength gains when compared to training to failure (6, 8).

And, the idea (mentioned earlier) of recruiting larger motor units under fatigue, being the key benefit has been found to carry one major flaw. Research has shown that the “extra recruitment” of the higher threshold motor units under fatigue plateaus around 3-5 reps shy of failure (14).

Meaning you don’t get the “extra recruitment” in the repetition effort method in the final few reps anyway.

Well, as we have discussed previously, this is where training volume comes into play.

Although I won’t go into too much detail and it’s not as important as training intensity when it comes to building strength (12), training volume still has a significant role to play.

A concept known as maximal recoverable volume (MRV) is the idea that we should train within the limits of what we can maximally recover from and no more. For example, research by Drinkwater et al. (5), found significantly greater improvements in bench press strength when training to failure.

With this study however, it may well be that the training volume assigned was within the MRV of the subjects, despite training to failure occasionally throughout the training intervention. They didn’t control for training volume at all. So some subjects were training out of the gym and some only doing what was told to do in the lab.

At the end of the day, it’s about balancing what you can recover from.

A recent study by Burd et al (3), found that muscle protein synthesis was greater following low load, high volume training (30% 1RM to failure) when compared to heavy load, low volume (90% 1RM to failure).

Great! Case closed…right?

Well unfortunately not. The main issue here, is that this particular study only investigated acute (24 hours) changes in protein synthesis; but did not look at the overall hypertrophic response long term.

One of the major selling points of training to failure was, “It stimulates the release of anabolic hormones like growth hormone and testosterone”. However, research has shown that acute changes in hormones are only weakly correlated to muscle growth (10) and not correlated to strength at all (15).

Finally, recent research by Sampson et al. (11) found that training to failure over a 12 week period actually resulted in completing MORE WORK for the SAME response when compared to a non-failure training group. Kinda pointless right?

*In case you’re interested, the non-failure group in this study, performed the exercise with a rapid lift and 2 second lowering phase.

Learn the implementation.

If you’re still adamant that you want to train to failure (or you want to use it as a method of incurring significant amounts of metabolic stress), then this is how it should be implemented.

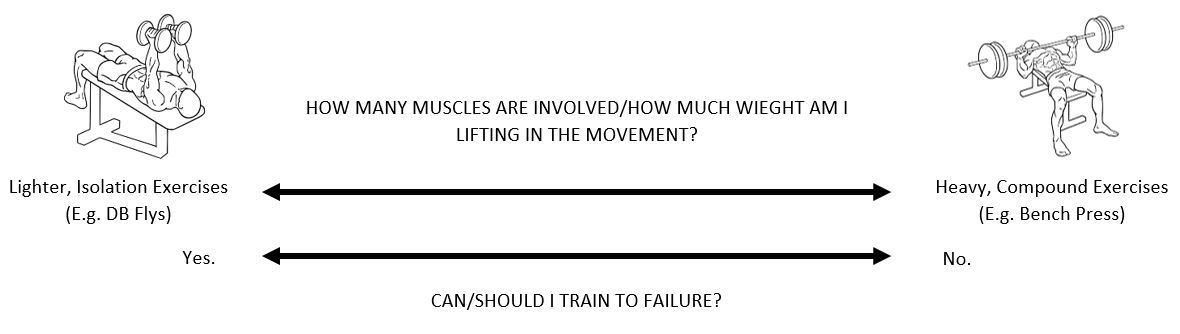

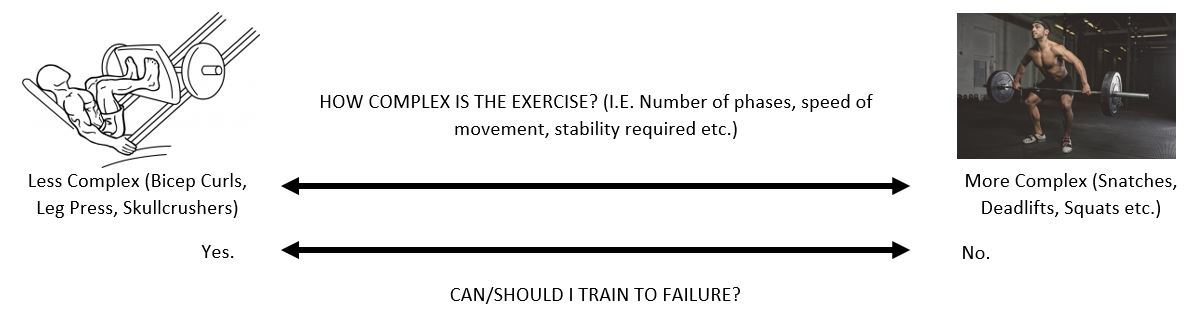

Avoid training to failure on compound exercises and complex movements. You can get away with training to failure on isolation/simpler exercises (even in larger muscle groups early on in your training career).

If you can’t ensure optimal recovery, work shifts or admit to being a relatively stressed individual, then I would recommend to avoid training to failure altogether.

However, this is never going to be the case and most people will disregard this due to the borderline sadistic pursuit of self-inflicted pain. Fortunately there is a final way to get the few benefits that training to failure brings, without causing too much of an issue on your recovery.

Larger muscles are capable of inflicting much more damage to themselves during strength training, and the opposite is also true. Smaller muscles, despite pushing them to the limits, will recover much faster than larger ones. Even if you perform an entire session on just training your arms, 24-48 hours later they will be good to go again.

Therefore, you can get away with going crazy and training to failure on smaller muscles (e.g. arms, calves, forearms, abs etc.) without negatively impacting the rest of your training cycle, increasing injury risk and the other downsides mentioned above.

What’s 3 x 10? 30 reps (Quick Maths)

Now, what’s ((1 x 12) + (1 x 8) + (1 x 6)) = 26 reps (Slightly Longer Maths).

Case 1 – Performed 30 reps and stopped 2 reps shy of failure on each set, but achieved a total of 30 reps.

Case 2 – Performed their first set to failure. But as a result, the fatigue meant that the next set, 8 reps was failure. And then the final set, they only achieved 6 reps before failing.

The first set for case number 2, messed up the rest of the training session and limited the overall volume they were able to achieve.

The point here, is if you are going to train to failure, in addition to only using isolation/less complex exercises with lighter loads, you should only go to failure on your final set. Otherwise it will negatively effect all of your subsequent sets.

Core Strength training often eludes most gym goers. Whether it's sticking to the same routine of crunches and side bends or simply neglecting it altogether - everyone could do with…

Ever heard of isometric Training?Arguably the most under-utilised, yet inordinately effective method of developing strength there is. Chances, many of you may have never heard of it. Or if you…

WHAT?Should I De-load?Everything was going well for Young Timmy in his training. It was all falling into place, with his strength seemingly continuing it’s never ending climb.Work was going well,…