WHAT?

With the number of injuries and ailments I’ve encountered not only with members of the public but with myself, I’d have to be an idiot to not spot some trends in the process of getting hurt and how people fix a workout injury.

You may have (or have had) a workout injury, whether it’s a little niggle every now and again or chronic and consistent pain. Does this mean it’s going to last forever? I thought exercise was supposed to reduce pain?

Why are you (or someone you know) in pain during exercise?

WHY?

Occupation + Congenital Issues

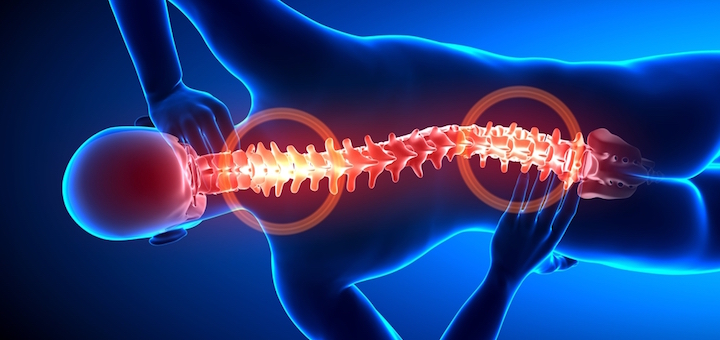

Although I could spend hours talking about the influence of posture on training results/adaptations (desired or otherwise), it’s worth noting that the two factors above are just a few of the many issues that have (and always will) significantly impact the likelihood of workout injury. For example, research and experience has shown, that sitting at a desk for prolonged periods has a negative impact on posture, causing the pelvis to tilt posteriorly (6) and often resulting in lower back pain (14).

With reference to congenital defects, physical abnormalities present from birth such as one leg being longer than the other can increase the chronic strain placed on the sacroiliac joint and ligaments (2). As a result, this is likely to always cause issues in the way you move. There is also some unique research highlighting the significant influence of the first year of life and developmental milestones during infancy, with motor skill and movement capability during adulthood (10, 12). “Great, thanks a lot Mum and Dad, it’s your fault I move so poorly” is what most would love to say. But the fact of the matter is, pain and workout injury are signals to the body to create change to remove the issue that is present.

Poking the Bear

There is an old saying that goes, “If you poke the bear, you’ll p*ss it off. So, don’t poke the bear and you won’t get hurt”. This idiom has a lot of truth to it. If a movement hurts, then don’t perform it.

However, what happens if that movement is a biomechanical archetype such as hinging at the hip?

I can 100% guarantee you right now, that if picking something up off the ground causes you pain and you (or god forbid a “professional” tells you to) stop picking things up off the ground…you can bet you’re in for a world of hurt at some other stage in your life.

Exercise is both Poison and Medicine

“The dose makes the poison” – Paracelsus

Removing exercise altogether is quite simply not the right answer. Even people who have suffered strokes and are unable to walk, significantly benefit and improve in a variety of physical factors when they perform exercises (1). The whole field of clinical physiotherapy is built on this very fact. However, many healthcare professionals have been trained to “deal with what’s in front of them” (due to a variety of different issues such as time constraints and financial pressures) and aim to fix the symptom rather than the root cause. What’s the easiest way of removing the symptom? Remove the stimulus altogether.

So, for all of you professionals out there telling your “patients” to avoid the gym altogether, until the pain goes away, I’d love to hear your rationale as to why this is a better solution than tailoring exercise to suit them.

It’s Not You, It’s Me…

“Squats hurts my knees”.

“Deadlifting hurts my back”.

I’m sorry but what did these movements ever do to you? Cut the bullying and leave them alone, they’re harmless…when used correctly.

All exercises are (and ever have been), are ways of loading/increasing the stress placed on the body within a given movement. Whether this stress comes from taking the fascia and muscle tissue to an extreme range of motion in stretching, or rapidly loading muscles and connective tissue during plyometrics is irrelevant. Because of this, you can’t blame the fact that the deadlift is hurting you. All you are doing is a loaded hip hinge. It’s the way YOU are doing it.

Change the Bear’s Attitude

Rather than avoid exercise, tailor it to fit your current circumstances. For example, if you struggle to deadlift on a straight barbell due to lower back pain. Research has shown that the trap bar deadlift has significantly lower lumbar compression than the straight bar alternative (13), so simply performing that variation still allows you to overload that pattern, whilst you work to fix the issues present.

The Big Reveal

Let’s face it, you set out on a mission to become stronger, leaner and healthier. But then those “damn and blasted exercise things with the weights and collars” hurt you?

Whilst they may have caused the pain, I’m afraid all they did was reveal what was already there.

At the end of the day if you sit down in a chair with knee valgus on a regular basis, 30 years of that and you’re likely to end up with damage to medial meniscus. Or you can perform a squat now, identify a dysfunction and work to correct it. It’s your decision.

![]()

HOW?

Priorities

What was your first goal? Why did you start exercise in the first place?

Now that you have identified an issue, doesn’t mean it should take over your primary goal necessarily.

Unless you’re in lots of pain (in which case that should be the first thing to address), every gym session doesn’t have to become a battle of wills to defeat the inner demon of poor movement and pain.

Make no mistake, there should be a focus on fixing things, but working up a sweat and firing out a few reps on a completely different, unaffected movement can still work you towards a goal.

Not to mention, giving you the psychological benefits that exercise has been shown to provide such as improved self-esteem and increased energy levels (3, 4).

Summary

Everyone has a movement dysfunction and should be acknowledged within the world of exercise. The main way to improve them, following mobilisation, is to focus on strengthening both muscles and movements.

A few examples include:

Lumbar lordosis? Strengthen deep core (5, 8).

Scapula Winging? Strengthen scapula protractors (7).

Patellafemoral pain? Strengthen hips (11).

*Note – this is not the only way to fix the issues above.

Although it is never that simple and several, more complex movement patterns need to be addressed (with the help of a professional) the key is your approach and mindset towards this issue.

Strengthening muscles and movements with corrective exercises whilst continuing to train around the injury is the answer. Not simply avoiding exercise altogether.

REFERENCES

- Ada, L., Dorsch, S., & Canning, C. G. (2006). Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 52(4), 241-248

- Cummings, G., Scholz, J. P., & Barnes, K. (1993). The effect of imposed leg length difference on pelvic bone symmetry. Spine, 18(3), 368-373

- Glenister, D. (1996). Exercise and mental health: a review. Journal of the Royal Society of Health, 116(1), 7-13

- Hansen, C. J., Stevens, L. C., & Coast, J. R. (2001). Exercise duration and mood state: How much is enough to feel better?. Health Psychology, 20(4), 267

- Ibrahim, E. The impact of using Pilates exercises on the electromyography of hyperlordosis for elderly

- Lin, F., Parthasarathy, S., Taylor, S. J., Pucci, D., Hendrix, R. W., & Makhsous, M. (2006). Effect of different sitting postures on lung capacity, expiratory flow, and lumbar lordosis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 87(4), 504-509

- Litchfield, R., Hawkins, R., Dillman, C. J., Atkins, J., & Hagerman, G. (1993). Rehabilitation for the overhead athlete. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 18(2), 433-441

- Mahdavinejad, R., & Rezaei, S. S. (2014). Pilate’s selected exercises effects on women’s lumbar hyperlordosis in immediate post-partum period. Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 2(2)

- Mörl, F., & Bradl, I. (2013). Lumbar posture and muscular activity while sitting during office work. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology, 23(2), 362-368

- Murray, G. K., Veijola, J., Moilanen, K., Miettunen, J., Glahn, D. C., Cannon, T. D., … & Isohanni, M. (2006). Infant motor development is associated with adult cognitive categorisation in a longitudinal birth cohort study. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 47(1), 25-29

- Nakagawa, T. H., Muniz, T. B., Baldon, R. D. M., Dias Maciel, C., de Menezes Reiff, R. B., & Serrão, F. V. (2008). The effect of additional strengthening of hip abductor and lateral rotator muscles in patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clinical rehabilitation, 22(12), 1051-1060

- Ridler, K., Veijola, J. M., Tanskanen, P., Miettunen, J., Chitnis, X., Suckling, J., … & Bullmore, E. T. (2006). Fronto-cerebellar systems are associated with infant motor and adult executive functions in healthy adults but not in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(42), 15651-15656

- Swinton, P. A., Stewart, A., Agouris, I., Keogh, J. W., & Lloyd, R. (2011). A biomechanical analysis of straight and hexagonal barbell deadlifts using submaximal loads. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(7), 2000-2009

- Youdas, J. W., Garrett, T. R., Egan, K. S., & Therneau, T. M. (2000). Lumbar lordosis and pelvic inclination in adults with chronic low back pain. Physical therapy, 80(3), 261-275