*Disclaimer: Whilst I understand that coaching squat technique is a rather subjective topic open to opinion, these 4 tips can be applied across a range of techniques and situations to boost your squat strength and aim to come from an objective, scientific standpoint as much as possible.

-

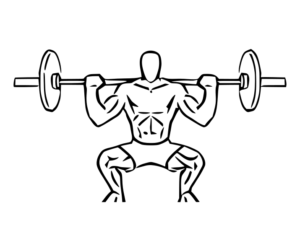

Selecting Stance Width

The aim for this section is to maximise the degree of muscle recruitment, whilst providing a comfortable and safe degree of movement. What this means is that although the research has reflected a wider stance of squat increasing the recruitment of the glutes, they have also found no changes in thigh muscle activation (9, 11).

This research is largely limited by the standardized depth that the subjects would descend to when comparing between groups. Unless you are an equipped powerlifter, choosing an extremely wide stance at the expense of your squat depth may not be optimal. In addition, a study by Caterisano (2) found that squat depth also significantly influenced gluteus maximus activation, therefore widening your stance specifically for increased glute activation may be obsolete, if squat depth becomes reduced due to flexibility and load.

This is due to the lack of balance, inability to utilise the stretch reflex effectively and uneven spread of load throughout the joints (e.g. most wide squatters are extremely hip dominant).

For most individuals, their best stance will be somewhere between hip and slightly wider than shoulder width. But as previously mentioned, find a width that allows you to take advantage of the stretch reflex, as well as maximising muscular recruitment. You may find that bringing your feet in a couple of inches will boost your squat within the same session!

-

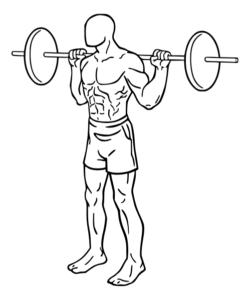

Utilising the Upper Body

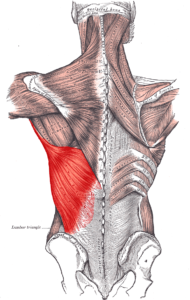

Simply because the squat is often banded as a lower body exercise, people completely neglect the effect the upper body has on your performance. However, considering the placement of the external load/bar, the upper body/torso plays a large role. The rigidity of the torso is a simple way to boost your squat strength by largely influencing the force transfer from the floor up to the bar and therefore the performance of the lift.

Research has identified the latissimus dorsi as a key spinal stabiliser when assuming a neutral posture/spinal position (5) as well as highlighting the significance of the trunk musculature in lifting tasks and reducing spinal compression (3, 8). Aiming to activate the lats by figuratively “bending the bar across your back” as well as “bracing the core” provides tension throughout the lats and other key spinal/shoulder stabilisers.

Research has identified the latissimus dorsi as a key spinal stabiliser when assuming a neutral posture/spinal position (5) as well as highlighting the significance of the trunk musculature in lifting tasks and reducing spinal compression (3, 8). Aiming to activate the lats by figuratively “bending the bar across your back” as well as “bracing the core” provides tension throughout the lats and other key spinal/shoulder stabilisers.

Think about most of the squats you have seen that people have failed. So many come from simply folding forward, the bar rolling up the back and thoracic (and god forbid lumbar flexion) occurring. When this does occur, the biomechanical leverages are wildly inefficient, meaning they lift becomes 10x harder than it should have been. If people fail like this, they know what to work on from that point onwards. However, if people train like this, focusing on the upper body aspect of the lift will potentially sky rocket the weight you can lift.

The coaching cue, “elbows forward” in the bottom may also assist with your torso position, however be wary that this may result in elbow tendinitis if not executed properly.

-

Weight Distribution

“Sit back on your heels”. “Wear Olympic Lifting shoes to elevate your heels”. You may be wondering about the confusion between weight distribution during the squat.

Although it may be largely subjective, from a bio-mechanical standpoint, the most ideal position is straight over the mid foot in order to align the centre of system mass (both the barbell and the mass of the lifter) over the centre of balance. If these two points do not line up, force may be lost somewhere during the movement.

Although it may be largely subjective, from a bio-mechanical standpoint, the most ideal position is straight over the mid foot in order to align the centre of system mass (both the barbell and the mass of the lifter) over the centre of balance. If these two points do not line up, force may be lost somewhere during the movement.

In addition, focusing on the even weight distribution also allows the lifter/coach/yourself to become aware of any asymmetry that may be occurring; with research highlighting well trained populations still running the risk of uneven weight distribution during bilateral tasks (10). If your body twists during a difficult rep, you are generating more force in one leg than the other!

A great way to boost your squat through this method is to actively focus on where your weight is being placed during your warm ups. It’s not something you want on your mind when you’re being buried in the hole by your new max. By that time it should be automatic!

-

Control the Speed of Descent

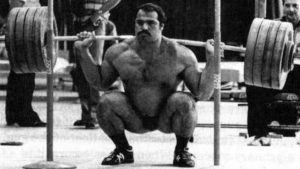

There are two extreme ends of the spectrum often observed during the squat. On one end, people will almost be apprehensive when descending and as a result, they lower themselves  (and the bar far too slow). On the other end, you see the “dive-bombers” or the “suicide squats” who essentially fall during the descent and bounce out of the bottom. Note that some squatters have become the greatest in the world from both methods, however for most people finding the balance between the two will be most beneficial.

(and the bar far too slow). On the other end, you see the “dive-bombers” or the “suicide squats” who essentially fall during the descent and bounce out of the bottom. Note that some squatters have become the greatest in the world from both methods, however for most people finding the balance between the two will be most beneficial.

Now this doesn’t have to just be identified by speed (although it is the most common issue) but these individuals descend far too quickly with limited tension in order to ‘rebound’ out of the bottom and utilise the stretch reflex.

Although the force produced from the stretch reflex complex is sensitive to the rate of change in length of a muscle (7), the key to effective utilisation is that the muscle must also be under large amounts of tension at all times. When people often attempt to utilise the rebound phase, they almost appear to “relax” in the bottom, this results in a quick rebound and an immediate, abrupt sticking point just before parallel.

Research has highlight that rapid movements utilised a greater amount of elastic energy from the muscle-tendon complex in order to enhance force (6). However, these tasks were plyometric in nature, which questions their application to high load, “slow stretch shortening cycle” tasks such as the back squat. Other studies have shown that slowing the movement down significantly results in greater involvement of the muscle and reducing “passive” contribution from the tendon (4).

The key here is to find effective balance. Going too fast, you run the risk of placing too much strain on the “passive elements” such as the tendons to recoil and produce force. However, going too slow means you may not benefit from the recoil at all and run the risk of stored elastic energy dissipating as heat (1).

The key here is to find effective balance. Going too fast, you run the risk of placing too much strain on the “passive elements” such as the tendons to recoil and produce force. However, going too slow means you may not benefit from the recoil at all and run the risk of stored elastic energy dissipating as heat (1).

Hope you enjoyed the article and learned a thing or two to boost your squat instantly! Leave a comment below if you have any questions!

REFERENCE LIST

- Anderson, F. C., & Pandy, M. G. (1993). Storage and utilization of elastic strain energy during jumping. Journal of biomechanics, 26(12), 1413-1427.

- Caterisano, A., Moss, R. F., Pellinger, T. K., Woodruff, K., Lewis, V. C., Booth, W., & Khadra, T. (2002). The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles. Journal of strength and conditioning research/National Strength & Conditioning Association, 16(3), 428.

- Cholewicki, J., & Vanvliet Iv, J. J. (2002). Relative contribution of trunk muscles to the stability of the lumbar spine during isometric exertions. Clinical Biomechanics, 17(2), 99-105.

- Cronin, J. B., McNair, P. J., & Marshall, R. N. (2003). Force-velocity analysis of strength-training techniques and load: implications for training strategy and research. Journal of strength and conditioning research/National Strength & Conditioning Association, 17(1), 148-155.

- Han, K. S., Rohlmann, A., Yang, S. J., Kim, B. S., & Lim, T. H. (2011). Spinal muscles can create compressive follower loads in the lumbar spine in a neutral standing posture. Medical engineering & physics, 33(4), 472-478.

- Ishikawa, M., Dousset, E., Avela, J., Kyröläinen, H., Kallio, J., Linnamo, V., … & Komi, P. V. (2006). Changes in the soleus muscle architecture after exhausting stretch-shortening cycle exercise in humans. European journal of applied physiology, 97(3), 298-306.

- Moritani, T. (2008). Motor unit and motoneurone excitability during explosive movement. Strength and power in sport, 27.

- Morris, J. M., Lucas, D. B., & Bresler, B. (1961). Role of the trunk in stability of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 43(3), 327-351.

- Paoli, A., Marcolin, G., & Petrone, N. (2009). The Effect of Stance Width on the Electromyographical Activity of Eight Superficial Thigh Muscles During Back Squat With Different Bar Loads. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(1), 246-250.

- Sato, K., & Heise, G. D. (2012). Influence of weight distribution asymmetry on the biomechanics of a barbell back squat. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(2), 342-349.

- Steven, T. M., & Donald, R. M. (1999). Stance width and bar load effects on leg muscle activity during the parallel squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 31, 428-436.