The benefits of squats. If any…what are they? And how will they influence your daily life and training?

You are home from work, tired and collapse into your favourite chair. Then stand up to grab a drink, switch on the TV (or hopefully head off to the gym). For you it may be an easy movement you take for granted.

But, are you doing it right? Are you moving correctly or efficiently?

Unsure? Ask the older generation for the answer.

Later in life it becomes progressively harder to execute these types of tasks and people often begin to repay the debt they’ve placed on the body due to poor movement over the years.

And due to the rapid decline in our health and overall activity the world over, this problem is only getting more common, more severe and earlier in life.

Fortunately, I’m not recommending you begin to take note of every time you sit down in a chair.

WHAT?

Learn the topic.

As luck would have it, the human body in it’s infinite wisdom responds and adapts to frequency, volume and intensity. If you place the body under large amounts of stress (i.e. practice the squat regularly in the gym), it will begin to adapt more to that stimulus, than the several times you sit down throughout the day. Below are just 7 benefits of squats and reasons to implement them in your training.

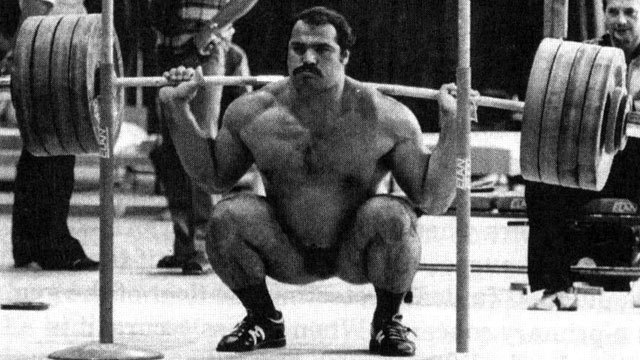

The Squat

The squat is heavily regarded as the king of all exercises. Not only in the world of strength and conditioning, but also within fitness, the benefits of squats make it a staple aspect of a large majority of programs and “routines”.

Yet as with most things, many people are unaware as to why the squat is such a beneficial exercise. Following on from the successful, “7 Reasons Why Absolutely Everyone Should Deadlift”, today’s article will provide you with a similar outlook on the primal movement, delving into a few of the benefits of squats.

What does the Squat Look Like?

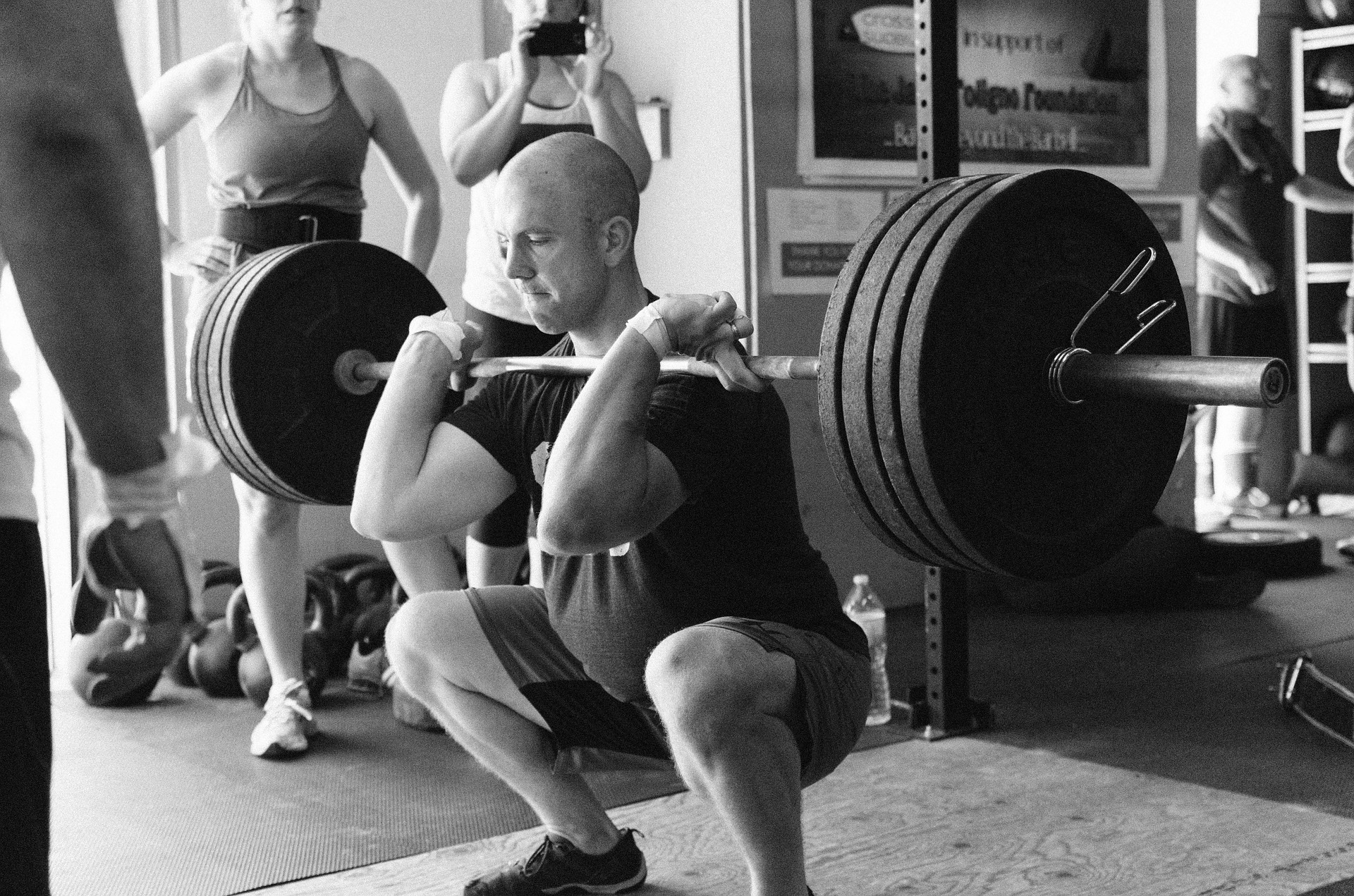

In an overly simplistic sense, the squat is a full body (yet lower body focused) movement in which an individual lowers their centre of mass, through flexion of the ankle, knee and hip joints towards the ground; keeping their chest higher than the hips at all times.

Although there is a huge degree of ambiguity regarding optimal technique and general execution (which will be covered in more detail in the future), the above description is basically the component parts.

You can hold a DB, sandbag, barbell, another human being for all I care and still receive the benefits of squats. But on the surface, the squat really is that simple. So why don’t people perform it regularly?

But Squatting is Bad for Your Knees, Right?

Every time I hear this comment I feel like I’m about to have a small seizure out of frustration.

Although that older guy in the gym who wears his weightlifting belt to do bicep curls and knee wraps for the leg press tells you squats are bad, doesn’t mean he’s right.

In fact, he couldn’t be more wrong.

When looking at the research, there is a significant body of evidence to show the benefits of squats to not only include improving knee health, but so much so they are becoming increasingly popular in the rehabilitative process when recovering from a variety of knee injuries such as patella-femoral dysfunction, right through to ACL reconstructions (9, 15, 19).

What if You’re in Pain??

Then it’s rather simple, you should either amend your technique yourself or have a professional review your movement competency and any restrictions you may have that need addressing.

As you will read soon, the squat is a foundational motor pattern that all healthy humans should be able to execute. If you can’t do this without pain, there will be compensation somewhere along the kinetic chain that will ultimately lead to chronic pain at a later stage in life.

So get it fixed ASAP.

The Squat as a Screening Tool

The benefits of squats are so important, that most movement screening methods will involve some derivative of a squat. From a professional’s point of view, it reveals an unprecedented amount of information about the way in which you will perform other movements and therefore is the starting point for a lot of corrective exercise protocols.

So much so that the founder of the Functional Movement Screen (FMS®) uses the deep squat as a primary tool for assessing a multitude of factors in the lower body such as ankle movement, lumbo-pelvic stabilisation and thoracic mobility.

So, let’s get right to it, the 7 Major Benefits of Squats.

WHY?

Learn the science and theory.

1. Lower Body Strength

Researchers and strength and conditioning experts the world over, agree the squat to be one of the greatest exercises for developing lower body strength there is. There is literally too much research to reference about the benefits of squats when it comes to building lower body strength.

All there is to be said, is that there are few exercises that hail in comparison when it comes to developing strength during hip and knee extension. So if you want to be strong, you need to squat.

2. Mobility of the Lower Limb

This is the primary reason why I prefer the deadlift over the squat (especially for beginners) but is also a key reason why everyone should have the capacity to and should squat on a regular basis. When looking into the biomechanics of the squat, most, if not all the joints in the lower body are taken into end range positions; especially when compared to exercises such as the deadlift.

This point also forms the origin for the widely discussed topic between strength and conditioning professionals regarding the depth to which someone should squat, with many people urging to avoid deep squats if you lack mobility.

Regardless of which side of the fence you sit on, it’s rare you will see someone capable of squatting comfortably to an end range position that doesn’t also possess dynamic mobility in many other movements.

3. Run Faster, Jump Higher

There is a plethora of research showing the benefits of squats, in structured training to improve one’s ability to run and jump.

Research has compared a variety of situations, from athletic individuals achieving acute improvements literally 5 minutes after performing a heavy squat (7), to marathon runners improving their running economy and overall performance, without increasing muscle mass, following heavy strength training (3).

It’s unanimous if you want to be a better athlete…

…you should perform the squat regularly.

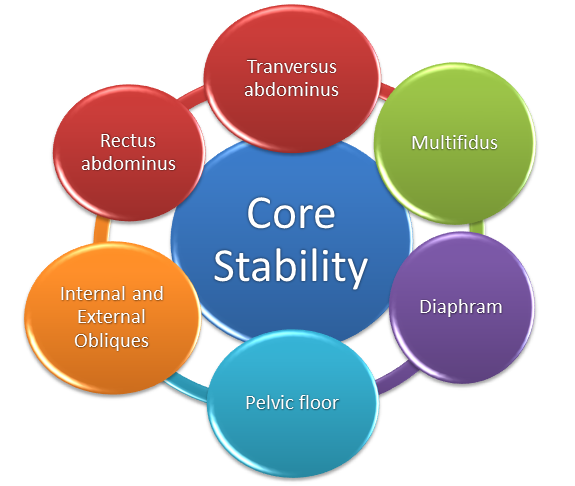

4. Core + Lumbo-Pelvic Stabilisation

Largely a product of point #2, when taking a joint to end range, the body requires increased recruitment of the musculature that provides dynamic stability (2).

This often results in the recruitment of muscles that usually do not actively contribute in everyday movement and are usually the muscles that are too weak to save you during injurious circumstances.

Due to the length-tension relationship, (in which a muscle has a decreased ability to produce force when stretched to extreme lengths; 20), other muscles that may be relatively inactive at “normal ranges” aid the prime movers in maintaining structural integrity and stability of a joint (2, 12, 16).

Furthermore, regardless of squat technique (wide or narrow stance), the lumbo-pelvic region is usually taken to an “end range position”. As a result, deep pelvic stabilisers such as the diaphragm, transversus abdominis and pelvic floor which are essential to aid with anterior lumbo-pelvic postural stability (11, 13, 14, 17, 18, 21) are recruited.

5. Maintain Cognitive Function

Although I will be covering this in detail in the future, there is an ever-growing body of research linking strength/power to the maintenance of cognitive function later in life (1, 5, 22), showing the benefits of squats to even extend to your brain.

Despite the prejudice, being stronger literally helps your intelligence.

6. Energy Demand

Not only is the squat capable of producing significant increases in muscle mass which will elevate your resting metabolism; the exercise itself is energetically demanding.

Research has shown intermittent squatting to result in a greater respiratory exchange ratio and similar heart rate values to continuous cycling (4). Although the acute caloric expenditure was lower, research has also shown the beneficial effects of regular resistance training on resting metabolism (10).

Essentially, one of the benefits of squats includes literally improving your aerobic fitness.

7. Glute Development

Few exercises hail in comparison to the deep squat when it comes to building a booty.

And there is a good reason why this is one of the major benefits of squats.

When in a deep squat position and using the same load, the deeper the squat, the greater the stretch (and therefore involvement) being placed on the glutes (6). Combine that with huge amounts of hip extension torque required to push out of the bottom position, you receive an extra special amount of glute recruitment.

*Note – the research has shown that when using a heavier load and a smaller range of motion, there is little to no difference in glute activation (8), however as mentioned above, there is a multitude of other benefits to be taken from deep squatting, leading researchers to recommend deep squatting if the individual can do safely.

Summary

- Squatting is a fundamental movement we should all be able to perform with safe and efficient technique

- Squatting is essential to build lower body strength, which in turn aids long term health, with research showing improved cognition function in elderly.

Reference List

- Alfaro-Acha, A., Snih, S. A., Raji, M. A., Kuo, Y. F., Markides, K. S., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2006). Handgrip strength and cognitive decline in older Mexican Americans. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 61(8), 859-865

- An, K. N. (2002). Muscle force and its role in joint dynamic stability. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (1976-2007), 403, S37-S42

- Beattie, K., Carson, B. P., Lyons, M., Rossiter, A., & Kenny, I. C. (2017). The effect of strength training on performance indicators in distance runners. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(1), 9-23

- Bloomer, R. J. (2005). Energy cost of moderate-duration resistance and aerobic exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(4), 878

- Cassilhas, R. C., Viana, V. A., Grassmann, V., Santos, R. T., Santos, R. F., Tufik, S., & Mello, M. T. (2007). The impact of resistance exercise on the cognitive function of the elderly. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(8), 1401-1407

- Caterisano, A., Moss, R. E., Pellinger, T. K., Woodruff, K., Lewis, V. C., Booth, W., & Khadra, T. (2002). The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 16(3), 428-432

- Chiu, L. Z., Fry, A. C., Weiss, L. W., Schilling, B. K., Brown, L. E., & Smith, S. L. (2003). Postactivation potentiation response in athletic and recreationally trained individuals. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 17(4), 671-677

- Contreras, B., Vigotsky, A. D., Schoenfeld, B. J., Beardsley, C., & Cronin, J. (2016). A comparison of gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, and vastus lateralis electromyography amplitude in the parallel, full, and front squat variations in resistance-trained females. Journal of applied biomechanics, 32(1), 16-22

- Dahlkvist, N. J., Mayo, P., & Seedhom, B. B. (1982). Forces during squatting and rising from a deep squat. Engineering in medicine, 11(2), 69-76

- Dolezal, B. A., & Potteiger, J. A. (1998). Concurrent resistance and endurance training influence basal metabolic rate in nondieting individuals. Journal of applied physiology, 85(2), 695-700

- Gardner-Morse, M. G., & Stokes, I. A. (1998). The effects of abdominal muscle coactivation on lumbar spine stability. Spine, 23(1), 86-9

- Hammoud, S., Bedi, A., Voos, J. E., Mauro, C. S., & Kelly, B. T. (2014). The recognition and evaluation of patterns of compensatory injury in patients with mechanical hip pain. Sports Health, 6(2), 108-118

- Hodges, P. W., & Gandevia, S. C. (2000). Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. Journal of applied Physiology, 89(3), 967-976

- Hodges, P., Holm, A. K., Holm, S., Ekström, L., Cresswell, A., Hansson, T., & Thorstensson, A. (2003). Intervertebral stiffness of the spine is increased by evoked contraction of transversus abdominis and the diaphragm: in vivo porcine studies. Spine, 28(23), 2594-2601

- Houglum, P. A., & Bertoti, D. B. (2011). Brunnstrom’s clinical kinesiology. FA Davis

- Lee, S. B., Kim, K. J., O’driscoll, S. W., Morrey, B. F., & An, K. N. (2000). Dynamic glenohumeral stability provided by the rotator cuff muscles in the mid-range and end-range of motion: a study in cadavera. JBJS, 82(6), 849-857

- McGill, S. M., Grenier, S., Kavcic, N., & Cholewicki, J. (2003). Coordination of muscle activity to assure stability of the lumbar spine. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology, 13(4), 353-359

- McGill, S. M., Norman, R. W., & Sharratt, M. T. (1990). The effect of an abdominal belt on trunk muscle activity and intra-abdominal pressure during squat lifts. Ergonomics, 33(2), 147-160

- Rasch, P. J., Grabiner, M. D., Gregor, R. J., & Garhammer, J. (1989). Kinesiology and applied anatomy. Lea & Febiger

- Rassier, D. E., MacIntosh, B. R., & Herzog, W. (1999). Length dependence of active force production in skeletal muscle. Journal of applied physiology, 86(5), 1445-1457

- Shirley, D., Hodges, P. W., Eriksson, A. E. M., & Gandevia, S. C. (2003). Spinal stiffness changes throughout the respiratory cycle. Journal of Applied Physiology, 95(4), 1467-1475

- Steves, C. J., Mehta, M. M., Jackson, S. H., & Spector, T. D. (2016). Kicking back cognitive ageing: leg power predicts cognitive ageing after ten years in older female twins. Gerontology, 62(2), 138-149