WHAT?

Without a doubt one of the most common phrases I hear thrown around by most trainers and gym goers. The idea of functional training.

“I don’t train my arms, they’re not functional.” – Whatever the hell that means?

“Do squats on a bosu ball, it’s more functional.” – I won’t even begin to elaborate. Instead just head over to https://www.strength-forge.com/functional-training-challenging-balance/ to read more.

“Lift a sandbag, or an awkward object, it’s more functional.”

Depending on your experiences so far, you may be on different sides of the fence in terms of what constitutes functional training. Thankfully, people are beginning to acknowledge that heavy, compound exercises are far more beneficial than lifting on unstable surfaces and all manner of fancy, colourful functional exercises you see nowadays. But even then, how can you be sure of optimal transfer from the gym to everyday life?

The answer is simple. As with most things in training…it starts with your movement capability. And more importantly, your approach to movement.

WHY?

Do You Even Lift?

This may sound odd, but ask yourself this question… Is the focus the weight you are lifting? Is the focus the bar or implement you’re lifting?

If so, you may need to change your approach.

I believe the idea of focusing on the exercise specifically is one of the main issues that limits transfer from the gym to life outside.

Particularly when you are new to lifting (or even for the experienced trying to learn a new exercise) more or less all the information you will find will be specific to the EXACT exercise.

This means that you will find a set of coaching/technical cues for the back squat and then if you want to front squat? An entirely separate list for that one.

Now don’t get me wrong, there are obviously differences between exercises with different bar positions, loading methods (e.g. bands etc.) and so on. However, there is one way to not only increase transfer to everyday life, but also speed up how fast you can learn other exercises.

Loading a Movement

This is the first and most paramount step to improve transfer from your functional training:

Stop learning exercises.

Instead, learn basic movement patterns, then learn how to load them in a variety of ways after the fact.

For example, before focusing on the differences between the conventional and sumo deadlift, learn the principles of performing an effective hip hinge. Once you know this, whether you are picking up a barbell, a boulder or another human being from the floor, you will be able to assume a safe and effective position, rather than panicking because the object isn’t evenly balanced on a barbell.

Where You’re Going Wrong

At the minute, when someone performs a specific exercise in the gym they should hopefully focus on the best technique and holding good, strong form. Then, however, when it comes to helping someone up off the ground or picking up a heavy object, they contort themselves into bizarre positions that are completely the opposite of what they do safely in the gym!

![]()

HOW?

3 Simple Tips to Find Similarities

When coaching someone new to lifting (or someone experienced in the wrong ways of lifting), I always find common principles of body position or movement execution across most exercises. A few examples are included below:

- Sternum Position = In most exercises you will perform (particularly those that load your spine) you should avoid a low sternum. Although it does matter whether this comes from thoracic or lumbar extension (don’t worry for now!), it’s important to focus on keeping your chest up.

- Triple Alignment in Lower Body = Whether performing a squat,

deadlift or more or less any compound lower body exercise, your ankle, knee and hips should all be aligned. Knee valgus/varus not only leads to a plethora of knee related injuries (8) but also decreases the force you can produce.

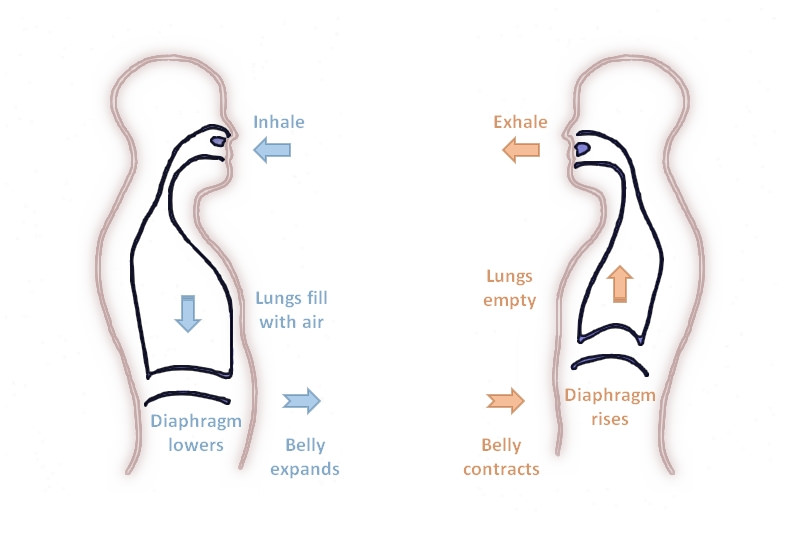

deadlift or more or less any compound lower body exercise, your ankle, knee and hips should all be aligned. Knee valgus/varus not only leads to a plethora of knee related injuries (8) but also decreases the force you can produce. - Breathing/Bracing = Although this will be covered in a separate article, breathing and bracing forms the foundation of core stability (7), ensuring trunk stabilisation (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) as well as optimising how much force you can produce in nearly all exercises, with research stating that no movement can be optimal without first addressing your breathing (6). Learning how to brace effectively will not only keep you safe in the gym but is a sure-fire way to keep you safe when having to jump start a car, lift a heavy object in work or anything else that may require the expression of your strength.

It’s Not That Easy

Now I’m not for a second suggesting that performing any form of loaded hip hinge as a form of functional training will automatically make you stronger when lifting a heavy boulder off the floor. There is OBVIOUSLY a huge element of muscular development in recruitment patterns that are specific to the exact movement, as I have spoken about before.

I’m simply saying that to improve the transfer of your gym training beyond what it currently is, focusing on factors such as the above, is much better than panicking when there isn’t a calibrated weight lined up in front of you ready to be lifted in a perfectly aligned sumo deadlift.

Summary

– Learn the principles of major movements first.

– Identify/look for common principles across exercises.

– Place these as a greater priority than simply the goal of moving the barbell from A to B.

Reference List

- Gandevia, S. C., Butler, J. E., Hodges, P. W., & Taylor, J. L. (2002). Balancing acts: respiratory sensations, motor control and human posture. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 29(1‐2), 118-121

- Hodges, P. W., & Gandevia, S. C. (2000). Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. Journal of applied Physiology, 89(3), 967-976

- Hodges, P. W., Sapsford, R., & Pengel, L. H. M. (2007). Postural and respiratory functions of the pelvic floor muscles. Neurourology and urodynamics, 26(3), 362-371

- Kolar, P., Neuwirth, J., Sanda, J., Suchanek, V., Svata, Z., Volejnik, J., & Pivec, M. (2009). Analysis of diaphragm movement during tidal breathing and during its activation while breath holding using MRI synchronized with spirometry. Physiological research, 58(3), 383

- Kolář, P., Šulc, J., Kynčl, M., Šanda, J., Čakrt, O., Andel, R., … & Kobesová, A. (2012). Postural function of the diaphragm in persons with and without chronic low back pain. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 42(4), 352-362

- Lewit, K. (1980). Relation of faulty respiration to posture, with clinical implications. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 79(8), 525-529.

- Nelson, N. (2012). Diaphragmatic breathing: The foundation of core stability. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(5), 34-40

- Sharma, L., Song, J., Dunlop, D., Felson, D., Lewis, C. E., Segal, N., … & Nevitt, M. (2010). Varus and valgus alignment and incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 69(11), 1940-1945